- Yosemite E-Biking - 01/12/2023

- The Yosemite Climbing Association - 09/01/2022

- Ryan Sheridan & Priscilla Mewborne - 05/17/2022

The birthplace of slacklining, Yosemite has inspired thousands of slackers throughout the world

By Chris Van Leuven

The Lost Arrow Spire sits high above Yosemite Valley (Julia Reardin).

Inspired by Steve Roper’s Camp 4: Recollections of a Yosemite Rockclimber (and a host of other reasons), I moved to Yosemite at the age of 18 out of high school in the summer of 1995. I was a brave, albeit reckless, climber willing to throw myself at just about anything. Thus, a few weeks after dropping my bags off in a white canvas Curry Village cabin and starting work as a checkout boy at the Village Store, my friend, the late Art Gimbel and I were huffing it up the 2,850-foot climb from Camp 4 to the great slabs on top of Yosemite Falls. Our goal? The Lost Arrow Spire Spire, one of the most famous objectives for rock climbers in the park.

After crossing a wooden foot bridge at the top of Upper Falls weighted down under hundreds of feet of rope and hardware, and baking in 80-degree temps, we crept down the slabs to get a closer look at the Spire perched out from the edge of the wall: a pencil of golden granite with a top no wider than three bodies standing side-by-side.

A few people gathered below us anchored to the wall and others were across 55 feet of stretched one-inch webbing extending over the void connecting to the top of the Spire. They were there “lurking” – the opposite of working hard, just hanging out in one spot doing nothing (yet taking in everything).

One of them, Darrin Carter, walked the line gracefully, surfing the springy line with ease as the wind pushed it around. I remember other vague bits of the day: distant figures finding balance on the line, ants in a giant landscape over an impossibly long drop, the wind blowing hard and cold through the notch that separates the Spire from the wall.

In 1995, Carter became the first person to walk that line, known as the “Holy Grail” of Yosemite highlines, untethered, as in free solo, with nothing to catch him in case he lost his balance.

My observations from that day, seen from afar but living among the tribe, is how I got familiar with the slacklining community over my decade-plus-long tenure in the park.

Early Years

Balance walking and slack-chaining, as in walking flat chains strung between steel fences, have been intertwined with Yosemite’s climbing culture as far back as the late ‘50s.

Pat Ament had been walking chains in a night circuit around Boulder, starting in about 1966. A university gymnast, he added this play of chain walking, balance, and turns on chains of many different lengths and weights.

Ament wanted ultimately to walk Ivy Baldwin’s 300 foot high, over 500-foot long, cable across Eldorado Canyon. He recruited a friend, Van Freeman, to help him string a thick steel cable similar to the Eldorado wire, in a secret location between two huge trees in the mountains west of Boulder. They practiced and prepared for the Eldorado walk and were able to borrow Baldwin’s pole from Eldorado proprietor Bill Fowler. They discovered, with the pole, their center of gravity was below the wire, and it was almost impossible to fall off.

Around 1968 or ’69, Ament and Freeman made a trip to Yosemite and brought a 50- or 60-foot slack chain to set up when they were not climbing rock. Ament’s friend and climbing legend, Chuck Pratt, joined in on the fun. Pratt had once thought of running away with the circus and had developed some skill on short wires and railings. Whereas none of the other Camp 4 climbers could stand on the long, heavy slack chain, Pratt stood up on one leg, established his balance, and for a few moments juggled three balls.

Ament was master of the wire, and could walk backwards and with eyes closed. It was erroneously reported that Ament “tried to introduce Pratt to the sport.” Ament was well aware of Pratt’s natural balance and past experience, and they simply enjoyed each other’s company. They strung the chain in Pratt’s camp. This was the beginning of chain walking in the Valley, and many people — through the next years — began to bring their own chains. Some experimented with rope and with sling materials. “Slacklining” had begun to evolve.

Unlike slackliners, Baldwin crossed a tensioned steel cable and also held a 26-foot pole to maintain balance. He did not use a tether and crossed the gap more than 85 times before retiring from the sport in 1948.

“Slack-chains in the ‘70s was my first experience,” photographer and longtime Valley resident Dean Fidelman told Adventure Sports Journal. “If you were living a climbing lifestyle, you slack-chained. If you didn’t, it meant you weren’t part of our culture.”

Success on the Spire

In 1983 Adam Grosowsky and Jeff Ellington attempted to walk the Lost Arrow Spire using a steel cable as Baldwin did in Eldorado Springs, but they broke a climbing anchor bolt on the Spire tip and retreated. The following year Chris Carpenter came with Scott Balcom, this time using lightweight one-inch webbing threaded with two pieces of 9/16 to try again.

“It was just too scary,” Balcom tells Adventure Sports Journal. “It was lonely, naked fear. I tried a bunch of times and kept falling. The one time I tried really hard I found myself diving into the Lost Arrow Chimney. I swung around and jumped onto the Spire like a cat out of water. I wasn’t psychologically prepared enough.”

A year of intense training later, in July 1985, Balcom walked it clean. Darrin Carter repeated the feat in 1993.

Yosemite big-wall legend and rescue team member John “Deucey” Middendorf remembers it this way: “Regarding slacklining in the Valley, we were inspired by Jeff and Adam, whom I met in Eldorado, and I brought the first slacklines to the rescue site when we were moved from Camp 25 to the corner site in 1984 and the chain came down, among other classic training equipment. This was quite a few years before the first Lost Arrow walk, of course, which is often recognized as the start of serious slacklining in the Valley.”

Libby Sauter, the first woman to walk the Lost Arrow Spire, completed the feat in July 2007. Shortly after, Jenna McLennan completed the second female crossing.

The late Dean Potter walked it both ways, untethered, in 2003. Then he added a longer exit line, increasing the challenge to 120 feet. Before his death from a wingsuit BASE accident in 2015, he walked both Lost Arrow highlines in free BASE-style. If he fell, he’d pull his chute and “turn dying into flying,” he wrote.

The Rise of the Monkeys

I was there for the rise of the Monkeys (1998-2008), a loose group of lurkers who resided in Yosemite for reasons beyond climbing rocks: they were there as part of a tribe of dirtbags, travelers and world-class athletes. Days were spent sharing 50/50s and drinking 16-ounce cans of King Cobra malt liquor by the slacklines, the boulders above Camp 4, the Merced River, atop the Rostrum and by the Lost Arrow Spire. These were all safe zones, away from ranger-danger. Mini parties broke out daily, with techno music tanging out of compact, portable speakers.

The Monkeys, Dean Potter, Leo Houlding, Renan Ozturk and Cedar Wright (to name a few), were part of the modern big wall free-climbers and speed-climbers era and we slacklined and highlined with boldness and vision. And we had fun.

The Rostrum

The Rostrum, a 700-foot rib of dark stone slashed with cracks, with its summit a half mile from the road, provided the perfect backcountry party venue surrounded with big-time exposure. The 75-foot highline extending from the wall to the top of the Rostrum proper attracted many first-time highliners and became a hot bed for visitors and locals alike. Adding to the scene, the late Dan Osman lured his friends out there to take wild multi-hundred-foot rope jumps off the top of the formation. It was also a BASE-jumping exit.

Dean Potter was the first to walk the Rostrum line untethered.

Dean Potter, King of the Monkeys

One of Potter’s tricks was that he would instinctively snag the line with his leg mid-fall (perfected by muscle memory from thousands of hours of practice) then right himself to a sitting position in one fell swoop.

Yosemite slackliner Chongo Chuck Tucker introduced Potter to the sport in 1993. Over the decades, applying what he learned from Chongo and adding to it, Potter went on to set the highest free-solo walk in the world, Taft Point, in May 2015. He completed this feat after aborting his efforts to walk a line 2,800 feet up on the side of El Capitan.

To succeed on the Taft project, located across the Valley from El Cap, he spent a week near the line, walking both it and a nearby low-line and envisioning success using meditation. “While my own experiences on the line had given me increased balance both physically and mentally, slacklining allowed me to grow,” he wrote in his story “The Space Between” in Alpinist 21 (Autumn 2007).

He continued: “Our foreign climber friends visiting the Valley brought the stoke home with them, and soon slacklining multiplied worldwide.”

The End of One Era and the Start of a New

With the Monkey tribe dissipating some 10 years ago came the rise of slacklining and highlining festivals. Today there are events in Tübingen, Germany, Baratti, Italy, Northwich, England, Saint-Laurent-d’Aigouze, France and Copenhagen, Denmark. And much more.

People still show up in Yosemite to highline but “that was kind of a Monkey thing, that’s how we hung out,” Fidelman says. “It’s not that same group who were living in Yosemite, Joshua Tree and Moab. It’s definitely not what it was.”

Chongo Chuck Tucker in Camp 4 (Tom Frost).

Corbin Usinger staying in control at Taft Point with El Cap in the background (Dean Fidelman).

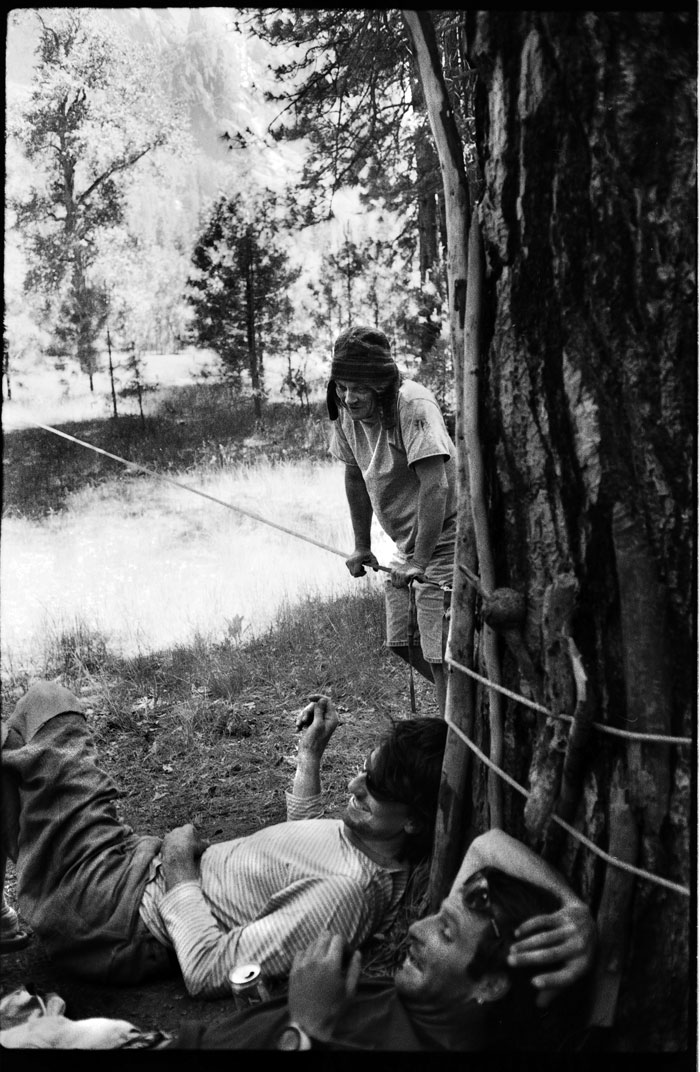

Chongo, Dean Potter, and Ivo Ninov relaxing in Yosemite (Dean Fidelman).

Dean Potter staying in the flow (Dean Fidelman).