- Tahoe’s Nevada Beach Tops the List of Hard-to-Book Campgrounds - 07/17/2024

- Cannabis Watershed Protection Program Cleans Up Illegal Grow Sites - 07/10/2024

- French Fire - 07/05/2024

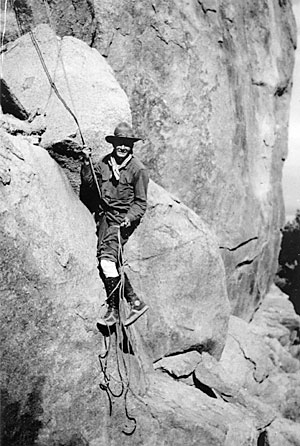

The Sierra’s Unknown legend

By Seth Lightcap

Photo courtesy of Norman Clyde’s private collection

In the annals of wilderness exploration, being the first to succeed at a given challenge has always been one of the primary motivators of inspired adventurers. The rich buzz of knowing not a soul has passed there before you is, human history would suggest, highly addictive.

Amongst the legendary explorers of California’s High Sierra, few men can claim as many first ascents as the legendary but little known mountaineer Norman Clyde. Between 1914 and 1940, Clyde made nearly 120 first ascents while tagging close to a thousand or so Sierra summits. His bold accomplishments stem from a lifetime of physical dedication to the Sierra unmatched by any other explorer who roamed the range before or after his era.

Who was this hardy mountain cat?

Norman Clyde was born the son of an Irish clergyman in Philadelphia on April 8, 1885. Throughout his childhood, the family moved frequently as his father rarely spent more than a year serving at a church. As they traveled, Norman was schooled by his father.

When Norman was 12, the Clyde family moved outside Ottawa. Amidst the surrounding forests and streams, he got his first taste of wilderness and grew fond of hunting and fishing. Meanwhile, under his father’s tutelage, he devoured classical literature and began to read Latin and Greek.

He entered college at 18 and though he could read Ulysses in Latin, Norman’s home schooling left him behind in other subjects. Nevertheless, he completed a degree in Classical Literature.

Upon graduating, Norman began moving west in stages. He taught in North Dakota for a year, in Utah the next. After two years of teaching, he decided he needed further formal education himself, so he enrolled at the University of California in Berkeley. Little did he know that this would expose him to the mountain geography that would guide much of his life.

For the next two years, Norman continued his studies in classical literature, while spending his summers exploring wild lands and teaching at summer schools in California and Nevada. In 1913, with only a single class and a thesis left to complete before graduating, he dropped out. He balked at the need to write a literature thesis that he felt no one would read.

Such a stubborn move was characteristic of his demeanor, though not a sign of low ambition. He was still driven to educate and returned to teaching at schools in Northern California. With his free time, he explored whatever mountains were within striking distance.

With a fresh focus on peak bagging, Norman slowly began making Sierra history. In 1914, he joined the annual Sierra Club trip to Tuolumne Meadows. After the rest of the group headed back to Yosemite Valley, he continued south along the Sierra Crest with a pack train destined for Lone Pine. On this trip he made the first two of his Sierra first ascents, Electra and Parker peaks, and also summited Mt. Whitney.

For the next 10 years, Norman jumped from classroom to classroom. He taught in Mt. Shasta, near Stockton, and in San Francisco. His next recorded first ascents occurred in 1920 when he caught up with a Sierra Club expedition to the Evolution Valley. Leaving Camp Curry, several days behind the pack train, Norman lugged a 90-pound pack of supplies. Fellow hikers were in awe, for Clyde weighed only about 140 pounds himself.

Norman wasn’t concerned with his pack weight. As far as he was concerned, he carried only necessities: a shoe cobbler’s outfit, several classical books, fishing poles, iron pots, and enough canned food to survive on for weeks. He became known as, “The pack that walks like a man.”

In between teaching and his solo expeditions, Clyde married a woman from Pasadena. Tragically, only three years later she died from tuberculosis. His heart was deeply scarred.

In 1924, he landed a job that would change his life. He was appointed as principal of the high school in the Owens Valley town of Independence. Living at the doorstep of countless Eastern Sierra trailheads, Clyde’s enthusiasm for peak bagging hit a feverish pitch. When school let out on a Friday he would quickly lock up and race to the mountains. Quite possibly the Sierra’s first true “weekend warrior” climber, Clyde bagged 48 peaks his first year in Independence, half of them first ascents.

His second year as principal he was even more prolific, recording 60 peak ascents. However, not everyone in Independence thought highly of his alpine addictions. Talk circulated widely that Clyde was not an adequate role model for a school principal. He never attended weekend functions at school nor church and many people felt such responsibilities were inherent in such a prestigious position. Yet Norman fought off his critics. Although he was absent during the weekends, the youth of the Owens Valley had never been controlled so diligently during school hours.

An incident on Halloween night in 1927 changed everything. Clyde had been tipped off that some rowdy boys in town were going to vandalize the school. He waited nearby, armed with a pistol to scare them off. When the car of hoodlums burst onto school grounds, he demanded they leave. They blew him off, so he fired a warning shot in the air. When this didn’t stop them, he fired a second shot, which reportedly ricocheted and hit the car.

The kids screeched away and promptly spread the story around town that the principal had shot at them. Clyde’s local foes immediately called the sheriff demanding his arrest. The sheriff denied to press charges, but in the end Norman was forced to resign as principal.

Photo: Eastern California Museum

Between the ache of a lost love and the burn of getting deposed, Clyde was now fully disenchanted with humanity. He succumbed to his reclusive instincts and began studying the High Sierra full time.

In the summer, he would live out of high camps that he had stationed in prime locations. When he wasn’t in the backcountry by himself, he made money guiding Sierra Club climbing trips and writing magazine articles. His writings describing some of his first ascents and the natural wonders of the high country were printed in the magazine published by the Auto Club of Southern California, a precursor to AAA.

In the winter, he worked as a caretaker at mountain resorts. Finding warm residence at such famous lodges as Glacier Point in Yosemite, Glacier Lodge above Big Pine, and Giant Forest in Sequoia, allowed him to spend much time touring about on skis.

With his mountaineering skills and backcountry knowledge, Clyde was often called to join search and rescue efforts for lost hikers, wrecked airplanes, or stranded climbers. One of his most famous recovery efforts occurred in 1933 while searching for the body of a young climber, Walter Starr Jr. Days after the search had been called off, Clyde found his fallen friend high on an exposed rock ledge below Michael Minaret.

Age didn’t slow Clyde down too much. Well into his 70s, he would hike up to camps in the High Sierra. Some of his patience for humanity seemed to return with age. He would dazzle Sierra Club members with gripping tales of his early adventures.

During his last years, he retired to a ranch outside Big Pine. He continued to venture into his beloved Sierra for as long as he could muster the strength. He died in 1972 at the age of 87.

In a fitting tribute his ashes were scattered from the summit of a stunning 13,851-foot peak along the Sierra Crest in the Palisade region – a peak which he made the first ascent of in 1930. It’s now known as Norman Clyde Peak.