- Tahoe’s Nevada Beach Tops the List of Hard-to-Book Campgrounds - 07/17/2024

- Cannabis Watershed Protection Program Cleans Up Illegal Grow Sites - 07/10/2024

- French Fire - 07/05/2024

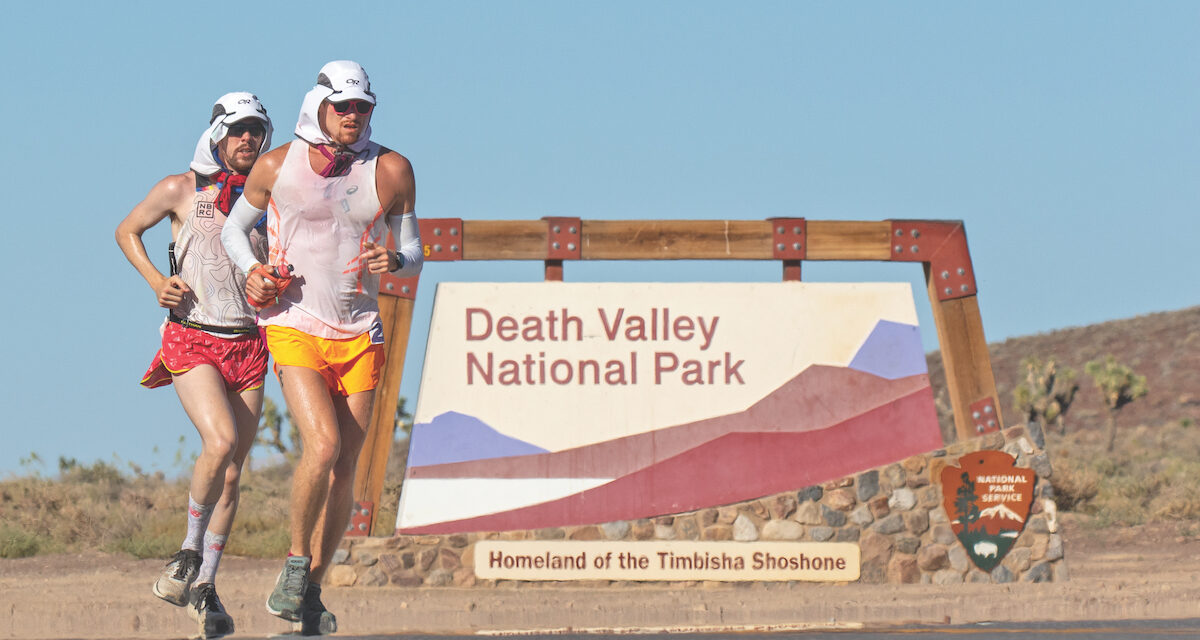

Badwater 135 — Where ultrarunners challenge the heat of Death Valley to the heights of Mount Whitney

The lowest place in the US is less than 90 miles as the crow flies from the highest peak in the lower 48. Every year, a gaggle of hard-core ultra runners follow the pavement from the sizzling salt flats of Badwater Basin in Death Valley National Park, 282 feet below sea level, to the lofty granite and dripping forests of Whitney Portal in Inyo National Forest at 8,374 feet, 135 miles away. On foot. In July. The Badwater 135 is the world’s toughest foot race.

Sure, there are races that cover more distance, climb more elevation or provide more technical challenge. But nothing compares to the Badwater 135. You can fry an egg on the pavement in Death Valley in July, and the whole course is on pavement. The elevation profile is bonkers. There are no aid stations.

“Of course, running 100 miles is never easy, but doing it on a flat course with cool weather is obviously way easier than 135 miles in July on pavement in the hottest place on Earth,” says Badwater World Series Race Director Chris Kostman.

Since Chris Kostman took over management of the race in 2000, it’s blossomed into more than a testing ground for the world’s most elite ultra runners. It’s a brand. It’s a family. It’s about chasing the horizon. It’s about embracing challenge. It’s a way of life. And under Kostman’s leadership, it’s expanded to include three annual races: the 51-mile Badwater Cape Fear, the 81-mile Badwater Salton Sea and the OG Badwater 135.

Even though Kostman has branched out to directing races in other places and even other countries, the Badwater 135 holds a special place in his heart. “I love what a dramatic place Death Valley is. I love big vast desert spaces, they humble people, help people realize how small they are and how big the planet is,” explains Kostman. “I love that the race goes from all that to finish in a forest, with a waterfall and granite spires. I love that the race goes from hot and dry to wet and cold. I love the communities we pass through, they’ve all really embraced our event.”

The National Park Service’s embrace of the event involves strict safety protocols. “We have one ambulance, a medical team of eight to ten doctors, nurses and EMTs, a total race staff of 50 people,” explains Kostman. “Each runner has a vehicle and a support crew with them; they need assistance every two miles on average.”

Ultra running is usually a solitary experience, but Badwater 135 is more like a team sport. “It’s like a homecoming every year,” explains nine-time finisher Joshua Holmes. “There’s this incredible group of people you see once a year and you get to know them really well, you get to know their support crews really well. We are out there competing against each other, but encouraging each other, too.“

“Even first and second place runners will help others, their support crews help each other,” says Kostman. “It’s like nothing I’ve ever seen at any sporting event, everyone wants everyone else to finish and have their best race ever.”

“This is an amazing event, it’s incredible what the competitors accomplish,” says Death Valley National Park (DVNP) Public Affairs Officer Abby Wines. “But it’s only possible because they have all these side rails in place for safety. A guy died a few years ago attempting the course without a support crew. We really discourage copy cats. Don’t try to do this on your own.”

The course climbs a total of 14,600 feet and 5,000 of that comes in the last thirteen miles. So after running 122 miles, participants have to complete the world’s hardest half marathon.

2022 finisher Malu Paredes of Venezuela gets cooling support from her team. Photo by Ian Parker

There’s no escaping the heat in Furnace Creek in July. Temperatures at 8pm regularly exceed 100 degrees and have been as high as 117. And, of course, it’s even hotter during the day.

There are no rest stops on the Badwater 135. “If we set up aid stations every three to five miles like other races, our volunteers would die of heat exposure!” Kostman explains with a laugh. The time cutoff was originally 60 hours but as runners got faster, the limit was dropped to 48 hours in 2011. Moving through the vastness of the Mojave Desert under your own power, when the next landmark you can see is 20 miles away, crushes egos.

And the obstacles are unpredictable. “We’ve had a forest fire at the finish line, a swarm of locusts, dust storms and a flood that closed part of the route during the race,” says Kostman. “Nobody enters this race thinking it will be easy, they generally know that anything can happen.”

Most long races have a lottery system for entry, but Badwater 135 is invitation only, and limited to 100 runners. So every January, the world’s most elite athletes vie for a chance to test their endurance on the course. In order to even apply, a runner must have completed a minimum of four 100-mile races, and have at least three years of ultra running experience.

And only nerdy athletes need apply. “Our race has five pages of rules because of the extreme conditions and government oversight,” says Kostman, “Badwater 135 is for runners and support crews who love to sweat the little details. We are looking for folks who are going to do their homework and show up understanding all the details and nuances of the event.”

“We are interested in more than what races they’ve run, we want to know what kind of athlete they are,” explains Kostman. “We ask them what they hope to achieve by participating in this event. We ask them why they are on this planet! We want people who will embrace the Badwater philosophy, who want to be part of the Badwater family.”

Joshua Holmes and crew member at mile 121 of the race. Photo Ian Parker.

“When I first heard about the Badwater 135, I could not fathom that kind of exertion in that extreme heat,” says Holmes. “I started doing 100-mile races, I even did a 314-mile race in eight days, but when I applied to Badwater I kept getting rejected. They said I didn’t have enough of a resume. The last time I got rejected I had done twelve 100-mile races. I thought that was plenty!”

Despite the stringent requirements, Kostman also wants to welcome a diverse field of competitors. Last year 40 women and 66 rookies from 26 different countries competed, setting records in each category.

The Badwater 135 boasts an 82% finishing rate, where in other ultras, which have a lottery system for entry, less than half the field may complete the race.

“Some races glorify their DNF — did not finish — rate, but I think that’s ridiculous,” explains Kostman. “We are looking for people who are capable of finishing. My goal is to host a fantastic event, but my bigger goal is to host an even more fantastic event next year. We do that by having a safe event that runs smoothly without incident. The best thing we can do is invite people who are likely to finish, and do it fairly and safely, without creating problems or drama. It’s sort of intentionally but not obnoxiously elitist.”

“When I first heard about Badwater, I thought aliens from another planet must come down to do it, it seemed like an impossible thing. I never thought I’d be at that level but it was something to aim for,” says Holmes. “Now that I’ve done it for a while it’s like a family. It’s the outliers of the outliers in the ultra community. At Badwater 135, you feel like you’re finally in a place where you’re among peers.”

2023 overall champion Ashley Paulson and her support crew at the Whitney Portal finish line. Photo by Chris Kostman

Learn more about Badwater 135 and other events produced by Chris Kostman at Badwater.com