- Climbing at Any Age - 09/19/2023

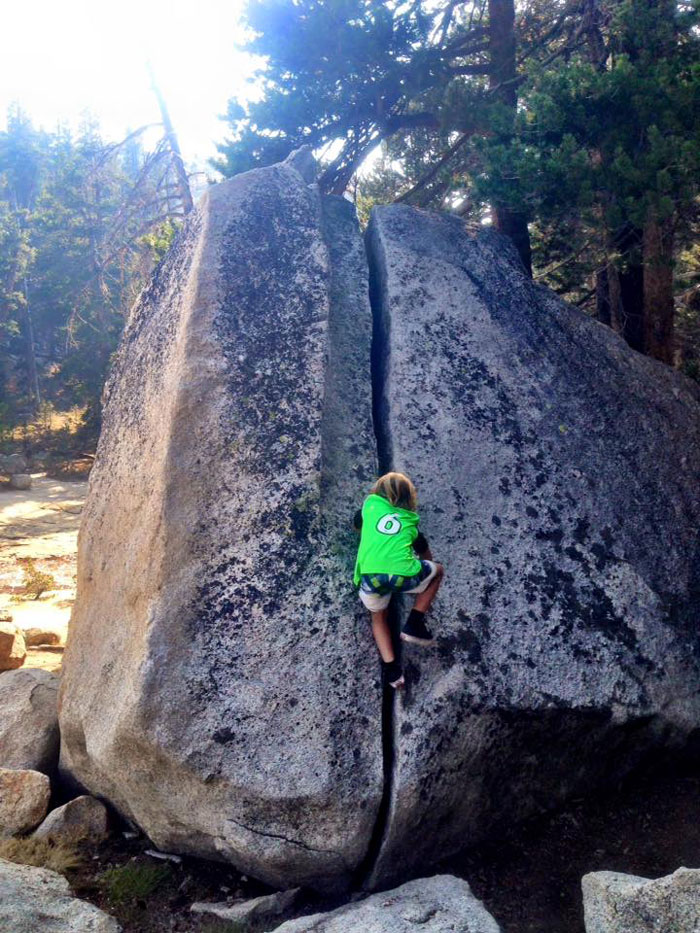

- Raising Conservation Kids - 10/20/2020

- Berkeley to Everest & Backin 14 Days - 01/27/2020

Adrian Ballinger: The journey from Tahoe to K2 is filled with suffering and joy

By Dierdre Wolownick

Suffering is rarely considered a positive motivator. But if you ask Adrian Ballinger about why he summited both Everest and K2 without supplemental oxygen, his comments often wander off into the terrain of how much suffering was involved.

An Eddie Bauer mountaineer, CEO and guide for Alpenglow Expeditions, Ballinger summited Everest without oxygen in 2017. This year he went back to Pakistan to tackle K2, the second-highest peak in the world which climbers call “Savage Mountain” because of its wild technical difficulty.

I asked him the obvious first question: Why?

“I know I can summit with oxygen,” he says simply. “I wanted to be challenged by the unknown outcome. That pushes you to a different level, a different mindset.

“These tallest peaks in the world,” he muses, his mind clearly back in the Himalaya, “they’re the pinnacle of challenge. While I was guiding on Everest in 2008, I found that the whole reason to go to these mountains is … they push you so far, and the outcome is unknown. I’ve always loved that, the not knowing. It challenges us to think about what we’re capable of.”

The list of peaks worldwide that Ballinger has summited or guided is impressive. But his climb of Everest without the benefit of supplemental oxygen, in 2017, did not lead immediately to his idea of attempting the same kind of challenge on K2. It took two years for that dream to coalesce.

“If I was going to continue summiting peaks without oxygen,” he explains, “I needed to know why. I kind of consciously kept the idea at bay.

“Then over that time (the two intervening years), I started to feel a need of that edge again … another peak where I could do something similar, go in stronger, train harder. I love technical climbing, and ice, so having something technically beautiful, more interesting began to sound like the right challenge. I was hanging out at Aconcagua (the 22,841 ft. peak in Argentina) with some of my closest friends, when Carla (Perez, a renowned mountaineer from Ecuador) mentioned, “I’m going to K2 …”

“That was it. The right team, the right people to try it with. I jumped in immediately. ‘Can I join?’” he asked her. And it became a goal.

It turned out it wasn’t a good season for it. By the time Ballinger and his team got to base camp, where everyone waits for the right conditions in order to summit, enough snow had fallen to convince all the other teams to head back down to safety. According to Ballinger, the snow was ‘chest-deep.’ Fighting that to the top, when they were already exhausted, was unthinkable.

So they waited.

Was this the ‘calculated risk’ he’d mentioned during our interview?

“Most importantly,” he clarified, “it felt like we just hadn’t suffered that hard yet! Usually these big mountains take two months. We weren’t even ready for a summit pitch yet. The others had been up there for quite a while, so they turned around; we were just up there watching, but hadn’t even had a chance to give it a go yet. So we came back down to base camp, knowing we had time. I persuaded our Pakistani officials to stay. We may not go anywhere higher, I told them, but we’re staying.”

Their patience paid off. Overnight, a ferocious 40-mile-an-hour wind picked up. It blew all night, ripping some of their tents out of the ice. By morning, it had cleared away almost all the snow, exposing the blue ice up on the traverse, the avalanche slope they had to cross. Their way up had been cleared.

“Patience was our only skill,” he summed up with a short laugh.

Surely not, but a lot of it was definitely required. K2 demands more technical climbing skill than many other 8000 meter peaks. But climbing skill alone will not get you up there. He explained the difference.

“Mountaineering hasn’t changed over the years, hasn’t progressed like rock climbing, where they’ve made amazing advances in the shoes and the gear. That changes what’s possible. But in mountaineering, it’s almost purely based on how well you suffer. And I suffer really well! When I was 17, I was in Ecuador hanging out at Mount Chimborazo (20,703 ft). I found out I’m good at managing pain.”

So, on the day before conditions cleared up, as most of the other mountaineers headed back down, Ballinger’s team settled in to suffer and wait. As it turned out, they only had to wait one day — but the suffering would last a lot longer.

Besides the wear and tear on their bodies from lack of oxygen, of sleep, of rest, the hardest part for their minds still lay ahead. The Bottleneck is a long couloir (corridor) between tall walls, whose entire upper section is a massive serac, or ice cliff. But ice moves. Melts. Falls. Refrigerator-size chunks of ice can come hurtling past you — or at you — at any moment.

The Bottleneck is the only way up. You can’t summit from the side of the mountain they were on without fighting your way through it, in both directions. There’s no getting away from it.

Which, of course, led to the obvious questions: Is it worth it? How does one keep such fear at bay, under a serac of that size and volatility? Are all the final good-byes said before leaving the States?

“Em (Emily Harrington, Ballinger’s life partner and world-renowned climber) and I do talk about risk,” he explains. “It’s a reality we both accept at a certain level. She challenged me about why K2 was worth it. I felt it was worth it to at least go up and take a look.”

So, as everyone else headed back down to safety, Ballinger’s team waited — and awoke to a brilliant, sunny day of blue ice and looming seracs. He ‘took a look.’

“I went through some cycles up there. Seeing the huge debris field underneath the Bottleneck, seeing the couloir, with no way to get away from it. All that getting ready, the suffering, the pain, the people … It became worth it. Worth the risk of dying.”

Maybe on one level. But on another …

“If you have oxygen,” he adds, “you can get through the Bottleneck in about two hours. I spent six hours under it. It felt so … random. Normally, I do everything I can to avoid randomness. To mitigate risk. This, though, felt so random. I’m willing to take on risk when I understand how to manage that risk.”

“When I came back down through the Bottleneck again (after summiting),” I stopped to shoot some photos — and I burst into tears! It was so intense! Six hours of thinking about dying … from completely random stupidity!”

Why six hours? What’s the big difference between having the supplemental oxygen or not? Those of us who have never been deprived of it have trouble imagining.

“It’s like comparing baseball to basketball,” he explains. “Both play out on the mountain, but they’re so, so different! It’s not just harder without oxygen; to me, it feels completely different. You suffer from nausea. An inability to sleep. To think. My brain just turns to complete mush. I can’t think of words, the simplest things. I lost 20 lbs, all muscle loss. There’s just a consistent breakdown of body and brain.”

He referred to the process as ‘a game of attrition.’ Climbers have only so many days until they’re too weak and too confused to continue. “You’re trying to find that balance, while you still have enough red blood cells.”

If that doesn’t sound daunting enough, there’s the last part, too; a climb isn’t over until you’re back on the ground. Or at least, on safer ground.

After losing 20lbs of his muscle mass and braving the nausea and brain mush to reach the summit, after agonizing through six hours — in both directions — of expecting house-size chunks of ice to come crashing down on him — he then had to hike 60 miles to get back to safe ground. I wondered how anyone musters enough of whatever it takes to keep going.

“For me,” he said, “it was dreaming about burgers. Ice cream. Whisky! Things you just can’t have. When we got back (to base camp), the local cook brought in two goats and butchered them. They were gone in a day and a half!”

Ballinger high above the clouds climbing the final summit slope on K2 (Esteban “Topo” Mena/Eddie Bauer Collection).

As he hinted several times during our conversation, suffering, or struggle, is an integral part of the extreme summit experience; ironically, or maybe logically, it’s also a mechanism that fosters happiness. The struggle is intensely personal — but no one goes up there alone. Teamwork got him down off Everest when his first attempt to summit without oxygen failed.

“I’d never really needed help before,” he recalls, “but everyone around me knew I needed help. I was very lucky to have good people around me. Ultimately it’s about these relationships, friendships, teammates, up there and beyond the mountains.”

An expedition of this type requires an enormous amount of support. I asked him whether his family and friends encouraged his attempt, or tried to talk him out of it.

“Em fully supported me, over time. She’s a climber, she understands these risks and passions. But she asked me challenging questions, to be sure. My ‘community,’ other friends, professional athletes — they understand chasing these wild dreams. My Dad, though, just thinks it’s stupid. He loves me, but he just doesn’t get it.”

As a mom, I get that. As a climber, I can’t help wonder about that suffering, those side effects. It seemed like a terrible thing to do to one’s body. Are the effects permanent — or does one just resume normal functioning, once back to sea level?

“My body bounces back,” he said, “as long as I work hard at it. Taking six months off from the big stuff (major climbs), focusing on the gym (instead of the outdoors), eating well.

“My memory loss, though …” He trails off in thought as he remembers. “I’m pretty conscious of it. I think there is some long-term stuff. I’m afraid that altitude makes it worse. So I’m just not planning the next trip yet.”

Yet. Ballinger still has a long list of dream ascents, like Kanchenjunga (third highest in the world at 28,169ft.) or Makalu (fifth highest, at 27,825ft.), both in the Himalayas. Maybe with oxygen, maybe without. Maybe even on skis …

Just don’t tell Dad.

Ballinger and his Sherpa climbing partner Palden Namgye on top of K2 (Esteban “Topo” Mena/Eddie Bauer Collection).

Ballinger arriving into Camp 3, 27,000 feet, on Mt Everest without supplemental oxygen (Cory Richards).

The entire K2 summit team back safely in Base Camp after a successful summit (Esteban “Topo” Mena/Eddie Bauer Collection).