- California Enduro Series Announces 2024 Schedule - 11/19/2023

- ASHLAND MOUNTAIN CHALLENGE 2023 – CES RACE REPORT - 10/04/2023

- China Peak Enduro 2023 – CES Race Report - 09/04/2023

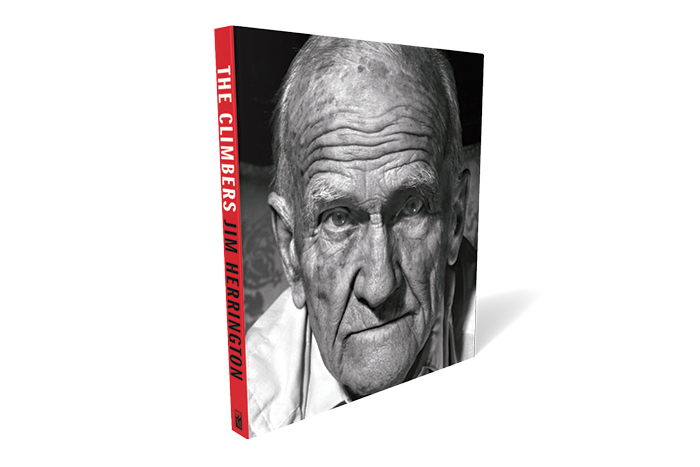

Jim Herrington’s book, The Climbers, exposes the deep inner lives of legendary mountaineers and climbers

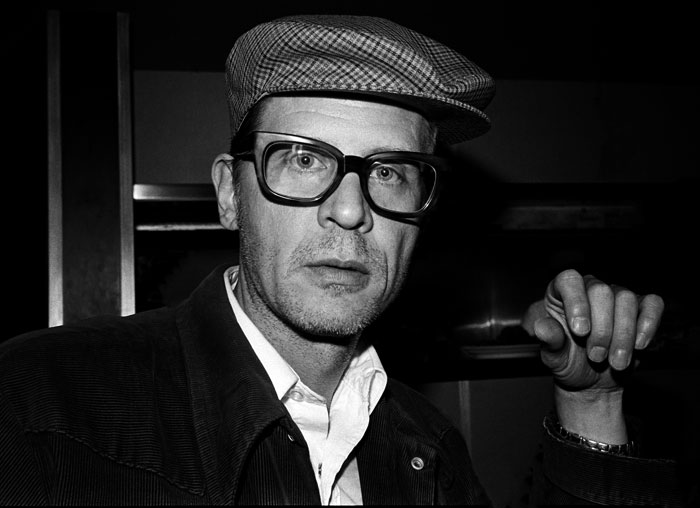

Coffee was brewing on the stove. From the looks of things, Jim Herrington had stayed up late. His thick brown hair, normally combed and coifed, looked like he’d just eaten an electric eel for breakfast. On the small kitchen table was a stack of film negatives, a loupe, contact sheets; the flotsam (keep) and jetsam (discard) of assembling nearly two decades of work into a major photography book — which at this time in May 2016 didn’t yet have a title. In his distinct patois — a mixture of SoHo New York City erudition, Nashville cordiality, and a slow dash of well-mannered Southern charm — he said that he’d stayed up late. He’d been editing photographs of the world’s legendary climbers.

Out the front window of the single-wide trailer on an alfalfa farm in the Owens Valley, a long, sage-covered lateral moraine swept down from the 14,000-foot Palisades, peaks in the High Sierra upon which many of Herrington’s subjects had plied their craft. Herrington was frustrated; he wanted to get up in the mountains that were so enticingly close, but work on the book was getting in the way.

Nineteen years. That’s how long The Climbers (Mountaineers Books, 2017) took. Between gigs photographing music and movie stars such as Tom Petty, Dolly Parton, Morgan Freeman, and too many others to mention without bruising your left foot from the name-dropping, Herrington was traveling around the globe methodically ticking off a list of legendary climbers while they were still alive. (And as I write this, just two weeks after the publication of The Climbers, another legend found in the book, Fred Beckey, passed away at the age of 94.)

“I was doing this all alone,” he says. “I was doing it when I had some money, when I could travel. And almost everybody agreed to varying levels of enthusiasm. There were a lot I didn’t get.”

Two rejections were memorable. One, the great Polish climber Voytek Kurtyka, wrote him back, saying, “. . . forgive me, it’s too difficult to take part in this spectacle which is, whatever the noble intent, a display of ‘the decay of heroes,’ this ‘march of death.’ Forgive me. I’m not ready yet,” and signed with the valediction “Friendly. Voytek.”

The other was Warren Harding, the Yosemite rabble-rouser to first nail his way up the Nose of El Capitan. Warren and Herrington had been imbibing in a string of tipsy late-night phone conversations and were getting pretty friendly with each other. Herrington was about to buy a plane ticket out to California to make Harding’s portrait. Then Herrington spilled a juicy bit of gossip about a climber he made a portrait of that was in keeping with the bawdy flow of the conversation. Something salacious, perhaps. As Herrington writes in the book, “He suddenly, ferociously, and very permanently put an end to our friendship, punctuated by a crescendo of bellowed verbiage and a final Herculean slamming down of his phone receiver with the combined force of every piton he’d hammered into the granite of El Capitan.”

Herrington lobbied for a blank page in the book to commemorate this exchange but the publisher didn’t approve. And it pains me not to be able to tell the intriguing story that Herrington told me off the record. But you’re welcome to ask him in person should you find yourself at his reading and slide show.

• • • • • • •

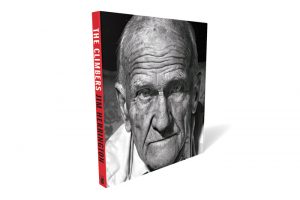

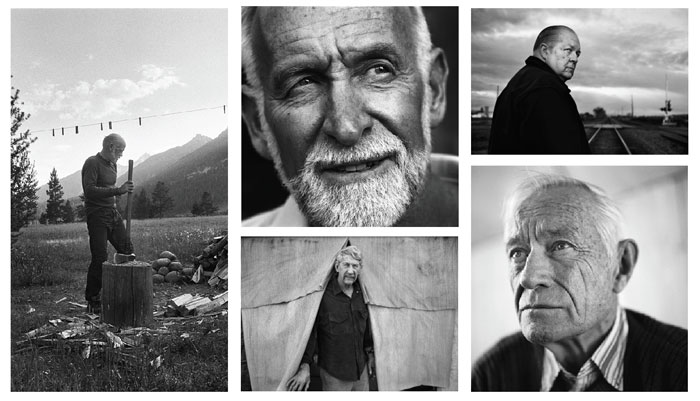

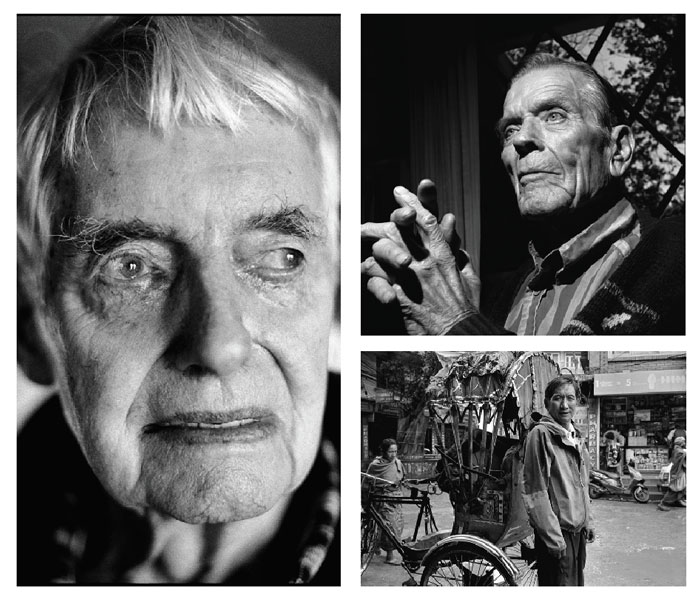

The Climbers is really the first of its kind. Featuring 60 seminal climbers from the early to mid-20th century, or as Herrington defines it, climbers who were vertically active between 1920 and 1970, the book is printed in black and white (and taken with analog B&W film). It isn’t meant to be an encyclopedia of every well-known climber within a particular era. Instead, it is a collective portrait of the global mountain landscape etched into the aging faces of climbers. Of men and women who devoted their lives to the pursuit of climbing and as a result, were given deep lives and rich lines.

As Alex Honnold writes in the introduction, “Jim Herrington captures the men and women behind the superhuman feats. His experience as a climber allows him access to their world, but his talent as a photographer is what brings them back to ours. In these portraits, we are reminded that great men are still men, sharing the same humor, motivation, and humanity as the rest of us.”

Little wonder the book won the Grand Prize at the prestigious Banff Book Award competition. Add to that the 30,000-word introduction to the book by highly lauded climbing and mountaineering author Greg Childs, which the even higher highly lauded climbing and mountaineering author David Roberts recently called “… a stirring apologia for the life of the mountains.”

Herrington began the project in 1998 thinking he would focus on Sierra Nevada climbers. “I wanted to meet the old guys from the 30s and 40s, and the first ones I got were Jules Eichorn and Glen Dawson who had done the first ascent of Mt. Whitney’s East Face in 1931 with Norman Clyde.”

Much in the same way he had sought out the legends of rock and roll and country early in his career, Herrington’s project soon expanded elsewhere with Bradford Washburn in Boston pulling it out of California, and still later into Europe and eventually the Himalaya, Japan, and other places.

“Climbing was an underground thing when these people were doing it,” Herrington says. “It was not something you saw on a Sprite commercial on TV or on a Twitter account. It was a punk rock thing to do.”

In person Herrington seems to have been transported from another era. His jean jacket, glasses, and haircut peg him somewhere into a very rock and roll late 50s, early 60s. But when he’s climbing he’s more likely to don a wool sweater and knickers rather than Gore-Tex and nylon. On occasion I’ve heard his bittersweet lamentations that he didn’t live in the daguerreotype or the wet plate era, to have been alive to photograph John Muir, John Tyndall, Clarence King, George Mallory, Norman Clyde — to name a few. During the multi-decadal project, he often worried if silver-based film would still be available by the time he completed the project and would be forced to shoot digital pixels.

“I’m an unapologetic romantic,” he writes in the book. “Show me a photo of a rain-soaked Don Whillans in 1956, soggy cig draped from his lip, hungover and grizzled from a bar brawl the night before, and twenty-five feet out from his last rattly piton, and I get all giddy inside.”

To find out what it’s like to be behind the lens of Herrington’s camera, I hunted down one of the youngest climbers to make it into the book. The climber — who happened to be hiding in the cushions of my couch — was Doug Robinson, resting up between Buttermilking sessions on Smoke Blanchard’s “Rock Course.” (Blanchard being another climber Herrington would have liked to photograph.)

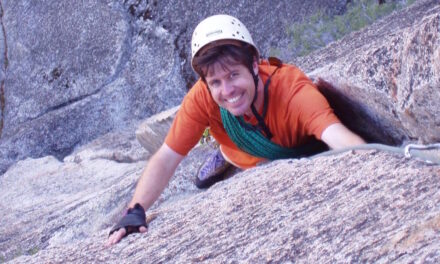

“I had never met Jim before he flew out from Nashville in the late 90s,” Robinson says, between bites of a cucumber. “And he’d come up from LA after he had photographed Glen Dawson, the first photographs he took for this project — before it was even a project. He rolled into camp seven miles into the backcountry, into my Palisade camp right below Temple Crag. I knew he was a good climber so right away we upped the ante to a first ascent on the unknown south face of Temple Crag, a climb that ended in moonlight and light snow on the last pitch. Halfway up the climb, with a storm brewing, I was staring down the crux pitch and I glanced over just in time to hear the shutter click on his classic Leica. The expression that showed up in the print says a lot about the situation and Jim’s relentless pursuit of a revealing portrait.”

• • • • • • •

What these portraits do reveal is often left up to the viewer to decide. Like a good song lyric, Herrington’s keen eye leaves enough room for both wonderment and interpretation. But what’s beyond dispute in The Climbers is the clarity of expression, the intensity of the gaze that seems to suggest these eyes have seen a lot of the world, have met fear and failures head-on, and have (or have not always) summited the world’s finest peaks. They, and ultimately all of us, climber or not, must face that threadbare mountaineer’s question of getting down off the mountain, or failing that, the descent into old age and (the) beyond.

Or maybe these revealing climber portraits have less to do with a keen eye and everything to do with Herrington’s inherent charm and friendly rapport with his muses, his heroes since he was a pre-teen ogling mountain boots and steel carbineers in a North Carolina climbing store. And to keep his heroes, our heroes, alive for all of us.

So when our own end comes — or even if we are young, nearly hit by rock fall or about to drop in on a monster wave — may we mutter the same noble words of Voytek Kurtyka, the Polish climber who rejected being included in The Climbers:

“Forgive me. I’m not ready yet.”