- Yosemite E-Biking - 01/12/2023

- The Yosemite Climbing Association - 09/01/2022

- Ryan Sheridan & Priscilla Mewborne - 05/17/2022

Pushing, maybe, a little too much

By Chris Van Leuven

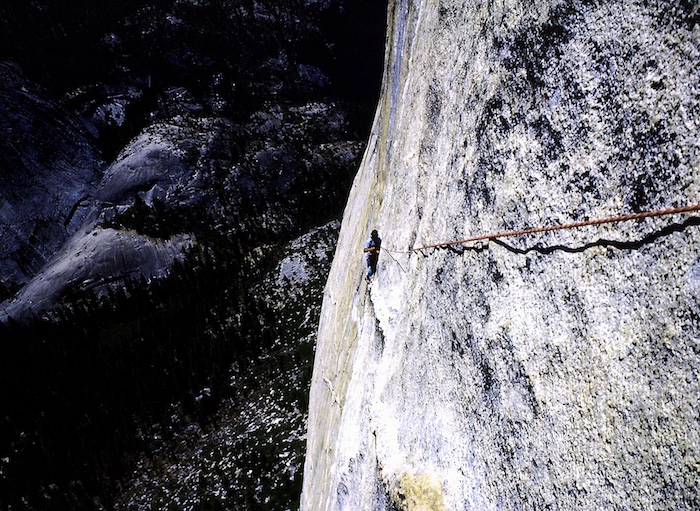

Brad Gobright high on El Capitan (Samuel Crossley).

Since the release of the documentary Free Solo, almost everyone has heard of Alex Honnold. But there’s another, lesser-known free soloist who is tearing up the scene: 30-year-old Brad Gobright.

It’s 1am in El Cap meadow. I’m pacing around in my harness and wearing a small backpack, waiting for Brad Gobright to arrive. In a few minutes we’re heading up the Big Stone for his hardest day of climbing to date: the 31 pitch (3,000′) 5.13 El Corazon. He’s planning a one-day-ascent, with hopes to be back to the Valley floor by 6pm. The route is so continuously difficult, with eight pitches of 5.12 and six of 5.13, that only Tommy Caldwell and Alex Honnold—arguably the most famous American climbers today—have freed it in a day. I’ve signed up to belay, carry supplies and clean pitches while ascending the rope behind Brad (which is hard in itself), but what he’s attempting is world class.

I only know Gobright from film, including Safety Third, which shows him ropeless on many long, hard routes (à la Honnold) as he builds up to and nearly peels off a 5.12 free solo to his death.

Early in the movie he falls attempting a 5.14 bolted crack on gear. He pulls the only cam keeping him off the deck, hits the ground from 20 feet up, and breaks his back.

The movie follows the always-psyched Gobright as he ticks a huge list of hard routes both with and without a rope.

The time-lapse film Two Nineteen Forty Four, shows him and partner Jim Reynolds setting the previous Nose record on El Cap. The two move in unison, sprinting up the route in perfection.

Back in El Cap meadow, right on time at twenty past one, Gobright pulls up in his car and proceeds to munch down a container full of blueberries and a bag of granola. Then we begin the 10-minute hike in. Gobright still lives the dirtbag life: his home remains his 2005 Honda Civic. He knows where and how to get the best deals on local grub. Other than having a steady check from his sponsor Gramicci and his secondary sponsor Evolv, he still lives like a homeless climber. His mom still pays his cell phone bill.

We reach the start of the route under 80-degree heat at 1:45am, which is a problem. He needs it to be cold, so his shoes stick to the slick granite and his fingers stay put on the razor-thin holds.

With his harness gear loops equipped with ten pieces of gear, less than is required for almost any route in the Valley, he sets off. My job is to carry water, clean his gear while on Jumars (handled ascenders that grip the rope) and keep up. The route is a complicated affair, with sections of loose rock, flaring chimneys, and fiercely hard moves up the huge wall.

He blasts up the first 50 feet placing nothing, then wiggles in a small cam and fires another 150 feet stopping twice more to place protection. This hybrid free solo technique allows him to travel fast and save energy.

I follow. It goes on like that for two hours and 45 minutes, where we make it 1,000 feet up El Cap.

Conditions were slick. It was hot and humid, forcing him to fight to hold onto the rock. He said there were spots, within 15 feet of his last point of protection, where he thought he could slip (which would equate to a 30-foot fall). In this controlled, or mostly controlled game, an unexpected slip could be deadly.

No go

At the top of our first objective, a section called Free Blast, he turned his headlamp to me and announced: “we’re bailing.”

“You’re too slow, and it’s too hot … you’re faster than 98 percent of other climbers out there, but this is the hardest climb I’ve ever tried and I need everything to be perfect.”

We retreat and catch a few hours of sleep. A few hours after sunrise, I meet him at his hang board workout behind the climber’s campground Camp 4. Here we plan our next objective for the day: the 700-foot 5.11 North Face of the Rostrum.

Thrashing and down climbing from the car down to the route, he suggests we do the 5.12 finish to the North Face called the Alien, one of the most exposed routes in the Valley. I decline, saying I’m not up for this one today, as I hadn’t climbed much in months.

I also talk him into doing just the top half of the route—to go down all the way to the start would have us rappelling past a hornet’s nest where someone I know had been recently stung. It was a risk he was willing to take, but not me. From the midway ledge he takes off, nearly running.

“I’ve never climbed with anyone like you before,” I said to him while dry heaving at an anchor. He moved fearlessly, without pause. I was along for the ride—at top speed as to not slow him down.

An hour after starting up, we’re on top of the route, making it in only a fraction it takes most parties. I’m out of breath and dripping with sweat.

As we hike up to the car he sums up the day, “It was cool climbing in the moonlight [on Freeblast]. But it was so hot on the Rostrum. It was the hardest it’s ever been for me.”

I’ve noted that as focused as Gobright was while climbing, he was equally un-focused on the ground; he’s often scrambled, forgetful and misplacing gear. And where his climbs are methodical, his home, or rather his basecamp, is a different story; his belongings are scattered about his car. I wondered if this ability to hyper-focus, is what drew him to climb such risky, high-level routes, again and again.

To keep his fingers strong, Gobright supplements his Valley climbing with weighted fingerboard hangs (Chris Van Leuven).

Always climbing

Growing up in the city of Orange in Orange County, California, “I was always into climbing trees and other stuff. I was into scrambling around,” Gobright says. “When I was eight, as a little gift, my parents took me to the climbing gym Rockreaction in Costa Mesa. They didn’t climb but they learned how to belay and they got harnesses and stuff and once a week they belayed me. I don’t think when they took me to the gym they knew that it would be my passion.”

After finishing high school and dropping out of college after one year, in 2008 he moved to Yosemite and got a job cleaning rooms at the Majestic Hotel so he could live and climb in the park. For six months a year for two years, dressed in his uniform of black pants and a black shirt, he pushed a cart from room to room, making beds, vacuuming, cleaning bathrooms, and wiping mirrors. When he wasn’t working, he pushed himself harder and harder on the rock.

From 2013 to 2016, when he was living seasonally in Boulder, Colorado, he would regularly free solo the 700-foot Naked Edge (5.11c), Colorado’s most famous rock climb, a feat he’s done (ropeless) between 25 and 30 times. (That’s a staggeringly high number of times to do a single route). He says doing it gives him the same satisfaction on a cardio level as doing a light jog. A jog where every step has to be executed with perfection or you fall to your death.

He lived in Boulder during the filming of Safety Third, where his free solo of Hairstyles and Attitudes at 5.12c remains the most difficult ropeless climb done in Eldorado Canyon. It’s a climb where he says he pushed too far to the edge.

“Hairstyles, I was like, eh, maybe I shouldn’t have done that. Maybe on that one I pushed too much,” he tells me over coffee.

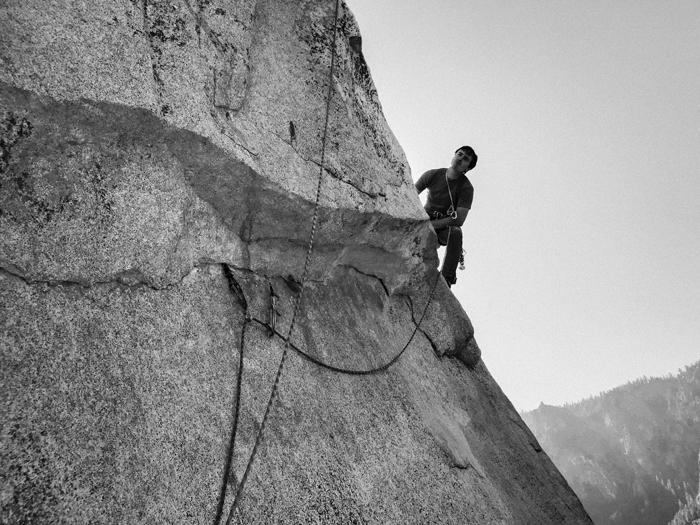

Gobright looking back on Freeblast during his training day for the one day ascent of El Corazon (Chris Van Leuven).

Meeting Honnold

On the same day after we do Freeblast and the Rostrum, Gobright and I meet up with Honnold at the premiere of the film Free Solo showing at the center of Yosemite Valley. We made our way through the crowd of hundreds to meet Honnold and soon the two soloists were talking like old friends, members of the close-knit climbing community who share a healthy competition with one another.

The way the media has shown it—which is true—once Gobright breaks a solo climbing record, Honnold goes to reclaim it. Soon after Gobright and Reynolds broke the Nose speed record in October 2017, the most famous route in the world, Honnold and Caldwell broke it, taking the time down and making news around the world when they made it sub-two hours. The soloists and speed climbers show equal admiration for one another.

Gobright’s success on the rock both with and without a rope puts him in an elite class, and it has caught the attention of thousands of climbers. His achievements include a rare one-day free ascent of El Cap’s Salathé Wall (5.13), considered by many to be the greatest big wall in the world. He’s also ticked nails-hard routes in Red Rock Canyon, Nevada, including the 10-pitch 5.13d DeeFree.

The next morning I meet Gobright at Camp 4 during his daily hang-boarding regimen. “I have ADD,” he professes during a rest. He’s in a surrounding of canvas tents and broad, colorful tarps strung between trees. Before I have a chance to respond, his stopwatch goes off and he jumps back on the wooden training board and hangs by his fingertips with a 25-pound weight clipped to his climbing harness. He says climbing alone isn’t enough to keep his strength and that hang board training builds necessary power.

Gobright admits his ADD has, at times, been embarrassing. He tells me about the time he gave a presentation at a climbing gym in California, and couldn’t remember the names of people he had known for years at the crags and gyms. After his show, the audience lined up for poster signings and he froze. He had to come up with excuses on the fly. “I was mortified,” he says. “That was one of the worst days of my life.”

But when it comes to climbing, Gobright never forgets a hold. He has, however, had his share of accidents. He once broke his toes when he fell off the top of Yosemite’s most famous boulder problem, Midnight Lightning, after deciding he didn’t need a crash pad because he’d done it so many times already. Once, he slid some 60 feet down a slab “approach” in Red Rock Canyon, Nevada, breaking his ankle.

A sense of purpose

I ask him what’s he’s looking for, aside from climbing.

“It’s just been a part of my life forever, all my best friends have come through climbing. It’s what I live for.”

His past injuries have forced him to take breaks, making him even more driven. He tells me that after Valley season he’ll train at the gym to build crimp strength and power, something he loses when climbing outside full-time. He says training on plastic for a stint also helps prevent burn out. “[Climbing] gives me a sense of purpose. It’s something I can continue to improve. I can’t picture myself as [anything but] a climber.”

A few days later he tried El Corazon again, this time with Camden Clements but, though they reached the top, he failed to free the route. Heat mixed with his exhaustion left Gobright greasing out a 60-foot-long roof traverse, the crux of the route. “It’s brutally difficult,” Brad said.

A week later, during a speed ascent of El Cap’s Realm of the Flying Monkeys, Clements fell 50 feet, broke a leg, and required a rescue.

The next time Gobright and I meet up, it’s for a sunset bouldering session on the blocs under Sentinel Rock. A crew of local paragliding instructors and BASE jumpers join in. By the time we get there, Brad has already run eight laps on a boulder problem traverse, all sans crash pads.

The group and I wander over to a nearby boulder to warm up. I offer Brad a pad as he makes his way over to the line we just did. He declines my offer for a pad. We look away for a moment and when we look back he’s on the ground in writhing pain.

He says he heard a pop in his ankle after he jumped for the final hold and came down hard on a rock at the base. “The season’s over,” he says while wolfing down a handful of ibuprofen I hand him. “I can’t imagine jamming my left foot in a crack for 3,000 feet by next week. By the time I heal, November, it will be too cold.”

On October 25 Gobright, with support by Henry Feder, freed El Corazon in 19 hours.

How Gobright poses for photos. He did this pose everytime (Chris Van Leuven).