- Tahoe’s Nevada Beach Tops the List of Hard-to-Book Campgrounds - 07/17/2024

- Cannabis Watershed Protection Program Cleans Up Illegal Grow Sites - 07/10/2024

- French Fire - 07/05/2024

How is it that dams actually hurt rivers?

— Missy Davenport, Boulder, CO

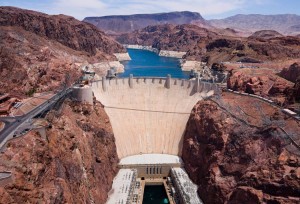

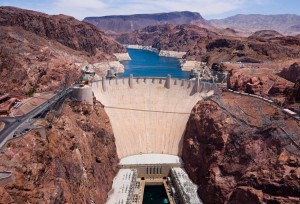

Dams are a symbol of human ingenuity and engineering prowess—controlling the flow of a wild rushing river is no small feat. But in this day and age of environmental awareness, more and more people are questioning whether generating a little hydroelectric power is worth destroying riparian ecosystems from their headwaters in the mountains to their mouths at the ocean and beyond.

According to the non-profit American Rivers, over 1,000 dams across the U.S. have been removed to date. And the biggest dam removal project in history in now well underway in Olympic National Park in Washington State where two century-old dams along the Elwha River are coming out. But why go to all the trouble and expense of removing dams, especially if they contribute much-needed renewable, pollution-free electricity to our power grids?

The decision usually comes down to a cost/benefit analysis taking into account how much power a given dam generates and how much harm its existence is doing to its host river’s environment. Removing the dams on the Elwha River was a no-brainer, given that they produced very little usable electricity and blocked fish passage on one of the region’s premiere salmon rivers. Other cases aren’t so clear cut.

According to the Hydropower Reform Coalition (HRC), a consortium of 150 groups concerned about the impact of dams, degraded water quality is one of the chief concerns. Organic materials from within and outside the river that would normally wash downstream get built up behind dams and start to consume a large amount of oxygen as they decompose. In some cases this triggers algae blooms which, in turn, create oxygen-starved “dead zones” incapable of supporting river life of any kind. Also, water temperatures in dam reservoirs can differ greatly between the surface and depths, further complicating survival for marine life evolved to handle natural temperature cycling. And when dam operators release oxygen-deprived water with unnatural temperatures into the river below, they harm downstream environments as well.

Dammed rivers also lack the natural transport of sediment crucial to maintaining healthy organic riparian channels. Rocks, wood, sand and other natural materials build up at the mouth of the reservoir instead of dispersing through the river’s meandering channel. “Downstream of a dam, the river is starved of its structural materials and cannot provide habitat,” reports HRC.

Fish passage is also a concern. “Most dams don’t simply draw a line in the water; they eliminate habitat in their reservoirs and in the river below,” says HRC. Migratory fish like salmon, which are born upstream and may or may not survive their downstream trip around, over or through a dam, stand an even poorer chance of completing the round trip to spawn. Indeed, wild salmon numbers in the Pacific Northwest’s Columbia River basin are down some 85 percent since the big dams went in there a half century ago.

While the U.S. government has resisted taking down any major hydroelectric dam along the Columbia system, political pressure is mounting. No doubt all concerned parties will be paying close attention to the ecosystem and salmon recovery on the Elwha as it unfolds over the next few decades.

CONTACTS: American Rivers, www.americanrivers.org; HRC, www.hydroreform.org.

EarthTalk® is written and edited by Roddy Scheer and Doug Moss and is a registered trademark of E – The Environmental Magazine (www.emagazine.com). Send questions to: earthtalk@emagazine.com. Subscribe: www.emagazine.com/subscribe. Free Trial Issue: www.emagazine.com/trial.