- Exploring Lava Beds National Monument - 07/15/2024

- Wandering Through Washington - 03/21/2024

- Striding Through Socal Sun, Storms and Snow - 12/27/2023

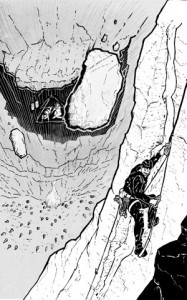

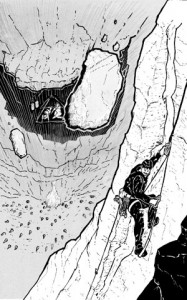

A selection from the new book, Yosemite Epics: Tales of Adventure from America’s Greatest Playground, compiled by ASJ contributor Matt Johanson. Back in the late ‘70s, backpacker-turned-climber Erret Allen and partner Mike Corbett rolled the weather dice and ventured onto the granite face of El Cap in late fall for a 29-pitch, week-long adventure. Their luck held out, for a while.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Illustration by Christopher Hampson

Backpacker Errett Allen hiked north on the Pacific Crest Trail from Southern California in the spring of 1974. Six weeks and 550 miles later, he detoured into Yosemite Valley to rest an injured knee. The visit transformed the “weekend warrior” who moved into Camp 4 for most of the next six years to test himself against Sierra granite. In later years, Allen prolifically established first ascents, many on difficult and rarely-repeated Tuolumne Meadows routes like Voyager, Breaking Wind and Blue Moon.

None of the climber’s adventures tested him more severely than El Capitan’s New Dawn line (5.9/A4). A worthy 29-pitch challenge in good conditions, the route becomes a nearly-unclimbable waterfall in rain and a deathtrap in snow. Falling rock and ice added still more peril to the life-and-death struggle which Allen, 27, and partner Mike Corbett faced in November of 1978. —Matt Johanson

I had no particular desire to suffer in wintertime, but fall was coming to a close and Mike Corbett and I wanted to squeeze in a wall climb. We really wanted to climb El Cap, which is such an immense challenge and takes so much preparation. New Dawn itself is a beautiful line, with a blank dihedral section that’s quite impressive, and Mike and I both had admiration for Warren Harding, who’d climbed it before.

The fact that we attempted it in November required extra planning and preparation. Short days, long cold nights and the possibility of a winter storm all had to be accounted for in our scheme. In addition, an aspect of the climb added to our potential problems. The route makes a long traverse to the right involving roped pendulums from bolts. This places climbers directly above a huge, steeply overhanging section of rock. Without the placement of many additional bolts that we didn’t have, the pendulums would be difficult if not impossible to reverse. Any retreat would be difficult even for experienced and healthy climbers. With either of us injured, it would be impossible. And if a winter storm caught us above this point, we would be forced to sit it out.

Our gear included rain suits, one down sleeping bag, a synthetic half bag, down jackets, bivvy sacs and enough layers of wool to swath 30 sheep. We also acquired (ahem) a primitive steel and canvas portable ledge; metal cots bolted to the walls in Housekeeping Camp served that purpose before climbers could buy a commercial portaledge. A two-man tube tent was rigged with duct tape as a rain fly. With the usual ton of iron, food and water for six days, our gear easily exceeded 200 pounds. For good measure I threw in my camera and a copy of “Atlas Shrugged” to read during those long winter nights.

We fixed ropes on the first three pitches and took forever doing all the borrowing, buying, organizing and packing that was necessary. This also helped delay the day of reckoning. We decided to fix one more pitch to boost our morale. Finally out of excuses, we blasted off Nov. 28 on a clear day with nothing but sun in the forecast.

Neither of us were early risers and it was nearly dark by the time we ascended our fixed lines and climbed the next three pitches. This was just as well since we were on Lay Lady Ledge – a large, comfortable place to camp. The climbing was easy so far and the weather was cold but clear. We knew at this time of year there are only a few hours of warm weather on this side of El Cap. Even when sunny, the mornings were cold, and just as things warmed up, the sun set behind The Nose and we would get cold again. The entire time we were on the route, temperatures on the Valley floor dipped into the low 20s at night.

The next day dawned clear and sunny and we were soon in the groove, smoothly sailing upward. I had one minor mishap on the day’s third pitch. The belay at the top is the ledge atop El Cap Towers – a narrow but long, flat and comfortable ledge. The anchors there at the time were three old bolts, probably placed by Harding 20 years earlier, none of which inspired confidence. I selected one which looked strongest to haul our bags on. As I strained to move them over a difficult section, the bolt suddenly pulled out. I flew back and found myself dangling in space, pulled down by the weight of the bags but held up by my tether to another bolt. After finishing the haul from this difficult position, we set up camp on the ledge. We fixed the next two and a half pitches before dark and then settled down for a comfortable night on El Cap Towers.

Another clear cold morning found us involved on the pendulum traverse and we were soon swinging like yoyos on a steep and exposed wall. After the traverse we were in a series of barely discernable and very shallow thin cracks that shoot up for several hundred feet. The climbing here is easy aid, but tenuous, involving many moves on Harding’s rivets that only penetrate the rock one-quarter inch. We knew from word of mouth around Camp 4 that we had to thread small wired stoppers over the heads of these rivets to clip our aid ladders in, but discovered to our chagrin that only the tiniest wired stoppers would work. We only had two of those. So we had to leapfrog our carabiners without leaving anything clipped in for protection behind us. Fully stimulated, we arrived at our next bivvy site called Wino Towers.

A few empty wine bottles we found here attested to the low moral character of our predecessors and we promptly broke out our own bottle. The ledge here is small, uneven and uncomfortable so our portaledge came into play for the first time. Though the sky was clear we set up the rain fly to shelter

us. All day long as we climbed we were showered by steadily increasing marble- sized drops from a waterfall on the rim. Unnoticed in the morning, the sun would slowly increase melting on top until by mid- afternoon there would be a steady stream.

The shower hit us sporadically up to this point and depended on how the wind was blowing. We relaxed that night listening to the pitter-patter of drops hitting our rain fly, oblivious to the danger awaiting us.

Again the sun greeted us in the morning. We packed our gear slowly with stiff limbs and sore hands and began climbing. Wind had picked up overnight and drops hit us early. After I led the day’s first pitch, Mike began the second under an increasing barrage of water. As I started cleaning

the pitch, the wind grew stronger and the shower got serious. Reaching the belay, I found Mike shivering uncontrollably and fumbling in the bags for our rain gear. I was still warm from cleaning the pitch but quickly I began to shiver, too. The drenching became worse by the minute and the sun took this opportunity to set behind The Nose.

We were in dire straits and would soon be hypothermic. About 30 feet above us was a bulge of rock that afforded protection from the shower so we climbed up there, hauled our gear up and quickly set up our portaledge and rain fly. To our dismay we discovered that all of our bivvy gear was soaking wet! We had been careless about packing it that morning. Plus, the practice at that time was to put bivvy gear in garbage bags to keep it dry, but in the course of packing and unpacking, holes had torn in the plastic. Everything had become soaked.

Fortunately we had lots of wool garments and after wringing them out as much as we could, we donned all of them. Facing each other on the narrow portaledge, we rubbed our hands and each other’s completely numb feet. Slowly and painfully, warmth returned to our extremities and we assessed our situation.

My sleeping bag, Mike’s half bag and our down jackets were no longer soaking wet. They were now frozen lumps of ice, completely useless. The wool we wore was slowly drying out, however, and we were warming up in our shelter. Retreat was completely impractical but we felt that our situation was not desperate and decided to sit out the afternoon and night. Hopefully with good weather we could continue to the top. That night was the longest and coldest bivouac of my life. With nothing but our wool to keep us from freezing, we spent the whole night rubbing what little warmth we could into our hands, feet and limbs. Sleep was impossible.

The sun rising bright and clear the next morning was a most beautiful sight. The waterfall abated overnight as the temperature dropped, freezing everything but us. We wasted no time packing and hurried to climb while we could do it dry and warm. Fortunately the next two pitches angled away from the waterfall. The climbing was slow, though, as four days of climbing and a cold, sleepless bivvy took a toll on our stamina. At every belay, we broke out some frozen pieces of bivvy gear and hung them from a rope clothesline, making El Cap look like an inner city slum. We must have been a sight from El Cap Meadow especially since we were the only guys stupid enough to be up there. Our down items never thawed in the cold weather, and we never got to use them the rest of the climb. That day we only completed three and a half pitches before nightfall – our slowest day so far. The one thing that lifted our spirits somewhat was that Mike’s half bag did thaw out enough to use for our next bivvy. So that night saw us ensconced on our portaledge with all four legs in one small half bag, not warm but better off than the night before. We were now 23 pitches off the deck and only five from the top.

High winds and whipping snow woke us the next morning before dawn. Snow was already piling up on our rain fly and gear and we wondered why we had ever taken up this stupid sport. We were about 100 feet below a small roof which was further protected by a huge roof 30 feet higher. Without even packing our bags, we climbed up under the first roof, hauled our junk and set up a new camp much more protected from the storm. Snow fell heavily and continuously throughout the day. Under the roof we were well protected with only an occasional gust of wind strong enough to blow snow over us. If it wasn’t for our exposed position and dwindling food, it would have been a pleasure to take a rest day. We had brought enough food for six days and this was our sixth day. We worried the storm might last several days so we tried to eat as little as possible. With strict rationing, we could stretch our supply for another couple days. The problem was the cold – it was more difficult to stay warm with no calories to burn. But for the moment we were protected, warm and safe.

I had read over half of my book by this time and tore it in half to give Mike something to relieve the boredom. Some of our friends came down to the meadow that day to ask if we were all right and yell encouragement. We shouted back that we were okay and didn’t want a rescue. Satisfied, they went back to the restaurants, bars and other amenities in the Valley. We spent the day as couch potatoes, reading, sleeping and daydreaming of warm beds and sumptuous feasts. An occasional foray outside the rain fly for nature’s call had to suffice to stretch stiff and sore muscles.

Though it snowed all day and most of the night, towards dawn it began to clear. To our delight, the sun rose and began to work its magic on our cold bodies. Our lighthearted attitude soon turned to dread as the sun also worked its magic on the thick snow and ice plastered to El Cap’s rim. A few hail-sized chunks fell past us. Soon larger chunks followed. We thought we would be safe under our small roof until a new phenomenon began. Blocks of ice two to four feet thick and as long and wide as railroad boxcars began to peel off the rim. They would flip over and over like playing cards, making an incredibly loud and dreadful whoosh with each flip. They fell in huge spirals that tracked far out from the wall and then tracked back in. More often than not, they smashed into the wall with great force breaking into thousands of pieces which showered the forest below. We quickly packed up and climbed the remaining 30 feet to the huge roof above us where we had much better protection from the falling ice. There we watched the most amazing show of nature’s power I have ever seen. To poke our heads out above the roof would have been suicide. Some ice slabs tracked halfway out to the meadow and crashed into the forest hundreds of feet from the wall. Some blocks tracked directly past us, unseen and unheard until suddenly they shot by with a terrifying whoosh that sent shivers up my spine. Around noon the ice fall abated. Since half the day was already gone, we resigned to spending another night on the wall.

The pitch above the roof provided more entertainment. It was aid climbing in a thin crack in a shallow dihedral. Near the top of the pitch, a spring gushed water which fell down the dihedral. Quickly freezing, the water filled the crack and covered the wall with a thick coating of hard ice. Mike took this lead and I could tell from many falling chunks of ice and his loud cursing that things weren’t pleasant. In order to get gear placements in that crack, Mike had to continually chip out the ice with a hammer and piton.

A long time later I heard his distant “off belay” and now it was time for my fun. I put my ascenders on the rope and when I turned the corner of the roof, I was presented with a nasty sight. The rope and all of our gear was frozen to the dihedral under a layer of ice up most of the pitch. Old-style jumars were famous back then for not working well on frozen ropes. The teeth on the jumars’ cams that normally grip the rope will quickly jam up with ice. Normally in any scary situation when following an aid pitch with jumars, climbers will “tie in short.” This means you tie directly into the rope every so often so that if your jumars fail, you will not fall all the way to the end of the rope. In this situation the rope was frozen so hard that it was a major effort, but I took the time to tie those knots.

For every placement of the jumars I had to first scrape off as much ice as I could with my fingernails, place the jumar and gingerly test it before committing full weight to it. I frequently had to remove a jumar from the rope to chip ice. Chipping the rope and the gear out of the frozen dihedral and crack wasn’t much fun either. All the time I cleaned this pitch, the spring soaked me just as it had soaked Mike. At least we were still in the sun. We could wring the water out of our clothes and continue climbing. We reached a small bivvy ledge and set up camp for another night, three pitches from the top.

The sun rose on our eighth day on the wall and it was very hard to coax our tired, sore, cold and hungry bodies off the ledge. We only had a few crumbs of bread for breakfast but the thought of the top so close spurred us on. The second pitch required aid with pitons behind a thin flake. Leading the pitch, Mike was about 25 feet directly above me hammering a piton when I heard a crunching sound. I looked up just in time for a 20-pound rock to slam me in the face. A chunk of the flake Mike had been nailing broke off. The right side of my face from forehead to chin became a bleeding and bruised mess as I learned what it’s like to be hit by a baseball bat.

I put a good scare into Mike. He told me later that he thought I had been knocked out or even killed. I determined I didn’t have any broken bones and reassured Mike I was okay. He continued the pitch. It was a really good thing I had looked up when I did or I would have been hit squarely on the top of my head, perhaps receiving a concussion or skull fracture. As it was I wore an attractive mask of scabs and scars for a while. One more sore spot on my body just blended in with the rest.

Mike graciously offered to lead the last pitch. With blood still running into my eyes, I concurred. Before long we pulled on top of the Captain at 11 a.m. on our eighth day. Though tired, sore, hungry and weak, we were completely elated at having survived and accomplished our goal through so much adversity. Having forgotten how to walk in the last eight days, we stumbled around and fumbled to pack our bags. We bantered about eating in a restaurant, sipping a drink in the bar and sleeping in a dry, warm bed in the evening to come. We thought our hardships were over and in just a few hours we would be surrounded by our friends and the comforts of the Valley. Such are the delusions of starved and confused minds.

We did have enough brain cells left to recognize we would have to be careful getting back to the Valley. Any experienced climber knows the climb ends only when you are safely back down where it started. The storm turned the East Ledges descent into an icy deathtrap. The alternative was to hike four miles to the Yosemite Falls Trail and then another four miles down to the Valley. While sorting our gear, we decided to leave most behind to carry as little as possible. Our heavy portaledge that had done so much to keep us alive, we tossed off the edge and watched as it flipped over and over, arcing in a spiral as it fell and reminding us of the ice from a few days before.

At first the hiking was on easy level ground, but two feet of fresh snow made it difficult in our exhausted state. After a mile or so, we faced an uphill section that rises to the shoulder of Eagle Peak. We soon found ourselves in a field of manzanita hidden under the snow. Mike sank to his knees most steps, and I would often plunge further even when using his tracks. Our feet become tangled in the manzanita, making progress excruciatingly slow. We got soaked from head to foot once again. Utterly exhausted, I stopped to rest and Mike was soon far ahead and out of sight. Eventually I crested the hill and followed on a spit over the fire, we managed to dry it out. Living to a ripe old age felt a real possibility again. I intended to stay awake all night tending the fire but exhaustion got the best of us and we awoke shivering at dawn.

Within ten minutes of starting out we encountered Yosemite Creek and turned downstream to follow the trail to the Valley. We were only about a hundred yards above the falls and soon stumbled down the switchbacks on frozen feet. Halfway down, we ran into Mike’s girlfriend Lisa who

was very concerned that we hadn’t shown up the day before. There had been talk of mobilizing a search for us. Before long we were back in Camp 4, surrounded by friends eager to hear our tale.

For several years, I suffered from poor circulation in my toes but my face healed nicely and fortunately I turned out no uglier than before. Did I mention that this was my first El Cap route?

I learned some valuable lessons on this climb. We could have been better prepared with waterproof gear and a stove, and we could have packed better so our stuff didn’t become soaked and frozen. I didn’t learn the most important lesson, as I went on to climb El Cap several more times. But I never did another winter ascent. From then on, I climbed The Captain only in warm, sunny weather.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Editor’s Note: Errett Allen, now 60, lives with his wife near Estes Park, CO, near Rocky Mountain National Park, and works as an engineer in the software business. He remains an active climber, though he hasn’t climbed in California for a few years. Though he has a “love-hate relationship with the Valley,” he misses summers in Tuolumne Meadows, where he was on the Yosemite Search & Rescue team for many years and guided for the Yosemite Mountaineering School in the late ‘80s. Co- author with Alan Bartlett of the 1988 book “Rock Climbs of the Sierra East Side,” Allen wrote this story about five years after the climb. It was never published, until book author Matt Johanson called after hearing about the tale. “I dug it up out of the garage,” says Allen. All these years later, he still hasn’t done another winter ascent. “One was enough,” he says. —PG