- Yosemite E-Biking - 01/12/2023

- The Yosemite Climbing Association - 09/01/2022

- Ryan Sheridan & Priscilla Mewborne - 05/17/2022

Legends of Yosemite: Tom Frost remembers the Golden Age

Words by Chris Van Leuven • Photos by Tom Frost / Aurora Photos

Yosemite Valley, September 1960. Royal Robbins, Joe Fitschen, Chuck Pratt and Tom Frost stand on a triangle-shaped ledge a few hundred feet up The Nose on El Capitan, setting their sights on making the second ascent of the route. To get there, they’ve scrambled up broken rock and ledges to the start of the route’s first pitch. Above them gleams 2,800 feet of glacier-polished, orange granite, sliced with black, dark gray and white streaks. Toward the top of the cliff’s highest point, a pink band of light touches the wall.

An hour earlier, the team loaded up by the side of the road with hundreds of feet of three-strand nylon rope, pitons, carabiners, slings, water, food and personal items. In addition, Frost was carrying Bill “Dolt” Feuerer’s Leica camera and seven rolls of film that Feuerer had handed to him the day before at the climber’s campground Camp 4. Feuerer had been active on the first ascent of The Nose a few years earlier. Offering the equipment to Frost, Feuerer said, “Take this with you, you’ll want to have it up there.”

Frost, now 80, at his home in Oakdale, California, recalled, “It was a pristine landscape. We were just enjoying the climbing. And to be there with these guys who knew what it was all about, you didn’t have to have a lot of conversation. The seven rolls I shot in those seven days were the best ones of my life.”

I first met Tom Frost 20 years ago in Yosemite Valley during the summer of 1997, after running into his son Ryan at the base of El Cap. I recruited Ryan for a belay on a route, and later all three of us met for dinner. I continued to visit with Frost whenever there was a chance, often to share a meal in Oakdale and swap El Cap stories before continuing on to Yosemite.

These include Frost’s Yosemite “Golden Age” stories from the 1960s. The Golden Age was an era of rapid change in Yosemite, with emerging techniques and philosophies from a small group of influential climbers. Few climbers had a bigger impact on the evolution of big wall climbing during this time than Frost and his partners Royal Robbins, Yvon Chouinard and Chuck Pratt.

Tom Frost, the younger of two brothers, was born in 1937 and raised in Hollywood, California. It wasn’t until his final year at Stanford University, where he studied mechanical engineering, that he discovered climbing through the Stanford Alpine Club. The group practiced climbing skills by top roping on the scrappy rocks around Palo Alto.

During his Yosemite visits with the Alpine Club, Frost noticed that climbers were working on El Cap’s Nose route. “We’d look up a million miles in the air and think, wow, Harding has ropes up there.” Frost graduated from Stanford in 1958, the same year Warren Harding, Wayne Merry and George Whitmore completed the first ascent of The Nose, an ascent spread over 45 days in two years.

Robbins slicing salami on Mazatlan Ledge on the North America Wall. End of Pitch 4.

After college, Frost moved to southern California and began climbing at Tahquitz Rock and also made two visits to Mount Pacifico. During the first of these trips, he attempted a thin, overhanging crack first climbed by Royal Robbins, which he was unable to complete because it was too difficult. Frost had yet to meet Robbins, but he knew of him by reputation. “His name was mentioned with an unusual amount of respect by these hard core climbers.”

Spurred by the challenge to succeed on the Robbins climb, Frost trained by climbing on the windowsills on the outside of his parents’ house.

When Frost later returned to Mount Pacifico, “To my horror Robbins was sitting on a rock right across from this climb.” Despite feeling nervous, he still managed to do the route. “I walked back down and he said, ‘Nice going.’ A few months later at Tahquitz, he asked me if I wanted to climb The Nose and I said yes. That changed my life forever.”

When Frost and his rope mates repeated The Nose — in what was only Frost’s second year of climbing — it took them a swift seven days. The ascent cemented a partnership between the four men that lasted the rest of their lives.

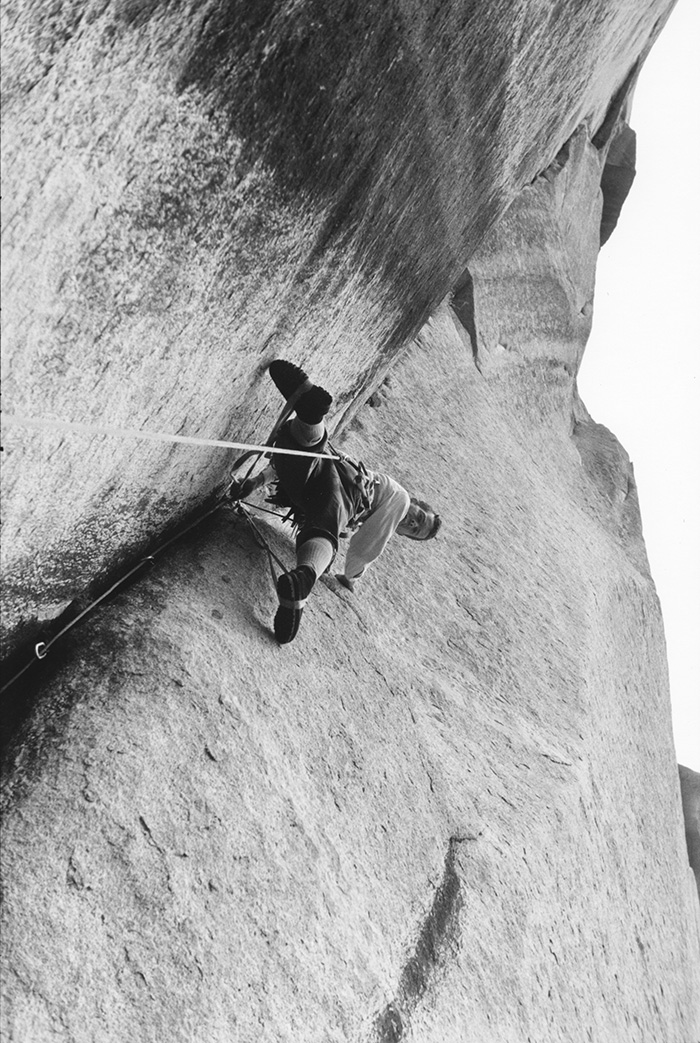

Frost belaying Pratt from a sloping Ledge during the first ascent of the Salathé Wall in September 1961. Pitch 23.

In 1961, Frost, Robbins and Pratt added a second route to El Cap, The Salathé Wall, a route still considered by many as the greatest rock climb in the world. In 1964, they teamed up with Yvon Chouinard for another first ascent on El Cap, the North America Wall, which was at the time the most difficult wall in the world.

“These routes were life changing experiences and I spent the next 50 years trying to understand their importance,” Frost said.

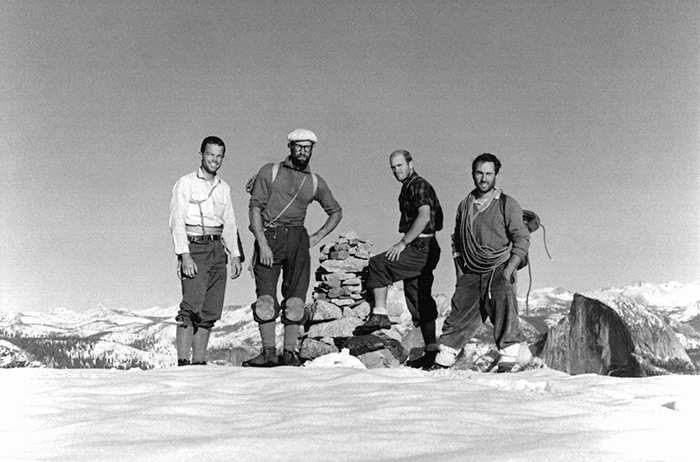

Frost, Robbins, Chuck Pratt and Yvon Chouinard on top of the North America Wall.

Frost’s motivation to finally understand what he witnessed all those years ago is because he’s the centerpiece of two biographies. One is a coffee table book by Yosemite big wall first ascensionist and climbing historian Steve Grossman. The other is a documentary film project by Tom Seawell and Jeff Wiant of Flatlander Films. Flatlander’s film is about Frost and the Golden Age, and in addition, the team has captured 60 hours of interviews from the world’s top climbers on how Frost has influenced their climbing careers.

Frost says that looking over the images from that era has helped him understand and recognize the influence those climbs had on his life as well as the lifelong friendships. He recalls Chouinard and his considerable business acumen. “I used to call him The Chief.” He also remembers Robbins’ strong leadership and realizes it was Pratt who quietly influenced him to recognize the spiritual relationship between himself and the rock.

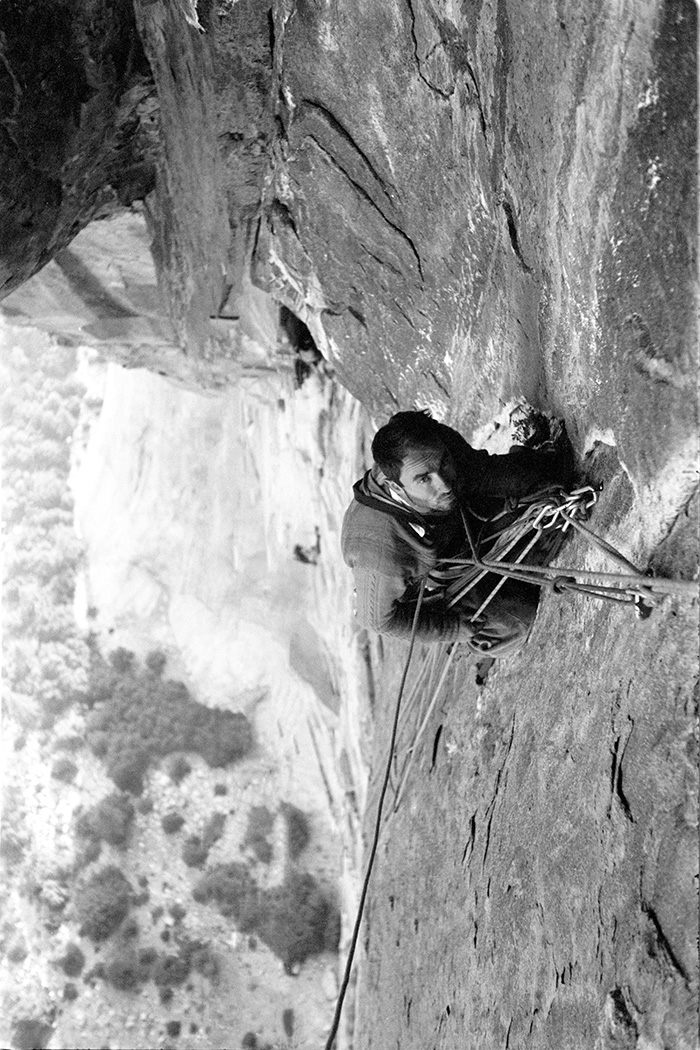

Yvon Chouinard at a belay in the Black Dihedral during the first ascent of the North America Wall. (Joe Fitschen).

“[Pratt] was on a personal basis with the climbs in Yosemite. They understood each other in ways that were greater than the rest of us. He was the most natural climber in the group and he had the strongest spiritual base. His actions were his main communications – he would show you, not tell you. He was exceptional.”

But he also sees something more. “When you spend a week up there, you know something bigger is going on than just getting exercise. I was really happy up there, really at home. As valuable as it was partnering with Royal, Chuck and Yvon, the deep impact during those climbs came from our partnership with the earth and earth’s spirit — the earth being a sentient being. It was that interaction, that intimate association and the struggle of the climb, and the close relationship with the rock. El Capitan and Mother Earth were providing the handholds and footholds. The earth is happy when we do a job and climb in good style and respect.”

“Most people’s eyes roll back in their head and they don’t have much to say. But you get it.” He lets out a huge laugh.

On March 14, 2017, Royal Robbins died after a long illness at the age of 82. “He was the real leader of the group,” Frost said. “He established the style – it’s not getting to the top but how you do it that counts. I was just a witness to his leadership.”

Pratt and Robbins arriving at the Cyclops Eye bivy on the North America Wall. End of Pitch 19.

After hearing of Robbins’ passing, I read one of his stories in which he, too, recognized Pratt’s unique relationship with El Cap. In Standing on the Shoulders: A Tribute to my Heroes, he writes of him: “He has always climbed, first and foremost, and last and finally, for the climbing experience itself, for the rewards that come directly from the dance of man and rock.”

Chuck Pratt passed away in Thailand in 2000. This leaves Frost as the sole survivor of the Salathé Wall’s first ascent party.

Frost’s climbing contributions also include walls in the Grand Tetons, the Northwest Territories and steep faces in the Himalaya. His innovative gear designs in the 1972 Chouinard Equipment “Clean Climbing” catalog influenced rock climbers to lessen their impact on cliffs and preserve the resource for future generations. Frost also played a critical role in saving Yosemite’s Camp 4 in 1997. His legacy of significant climbs and dedication to Camp 4’s preservation earned him the Excellence in Mountaineering Award from the American Alpine Club in 2016.

Chuck Pratt and Royal Robbins on El Cap Spire during the first ascent of the Salathé Wall in 1961 (Tom Frost).

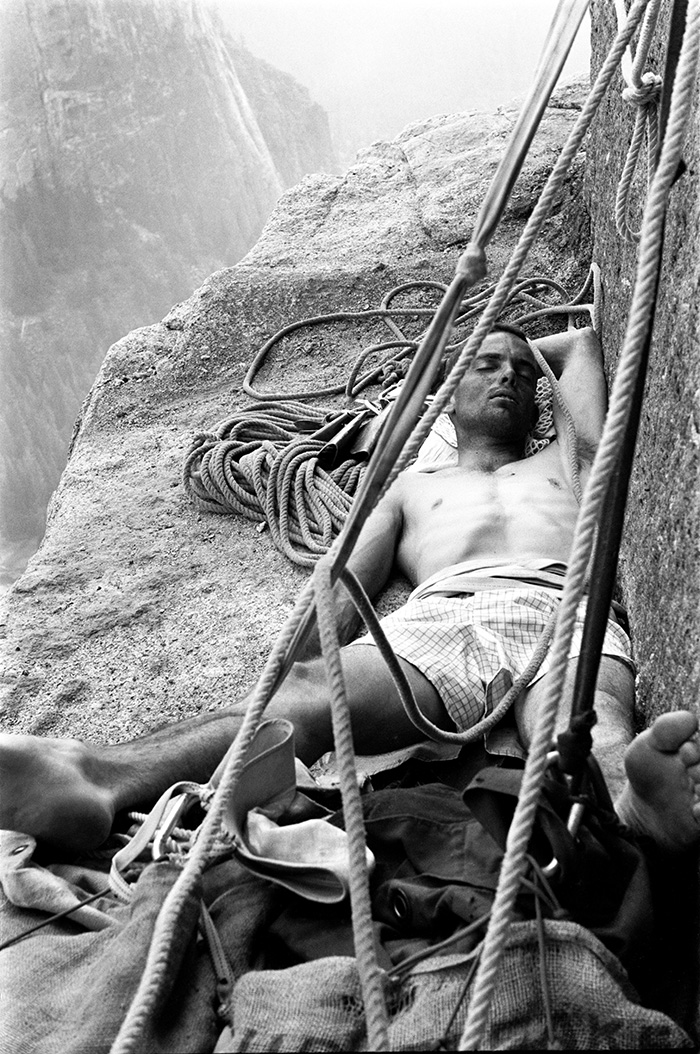

Frost exhausted from the previous day’s hauling efforts during the second ascent of The Nose, September 1960 (Joe Fitschen).

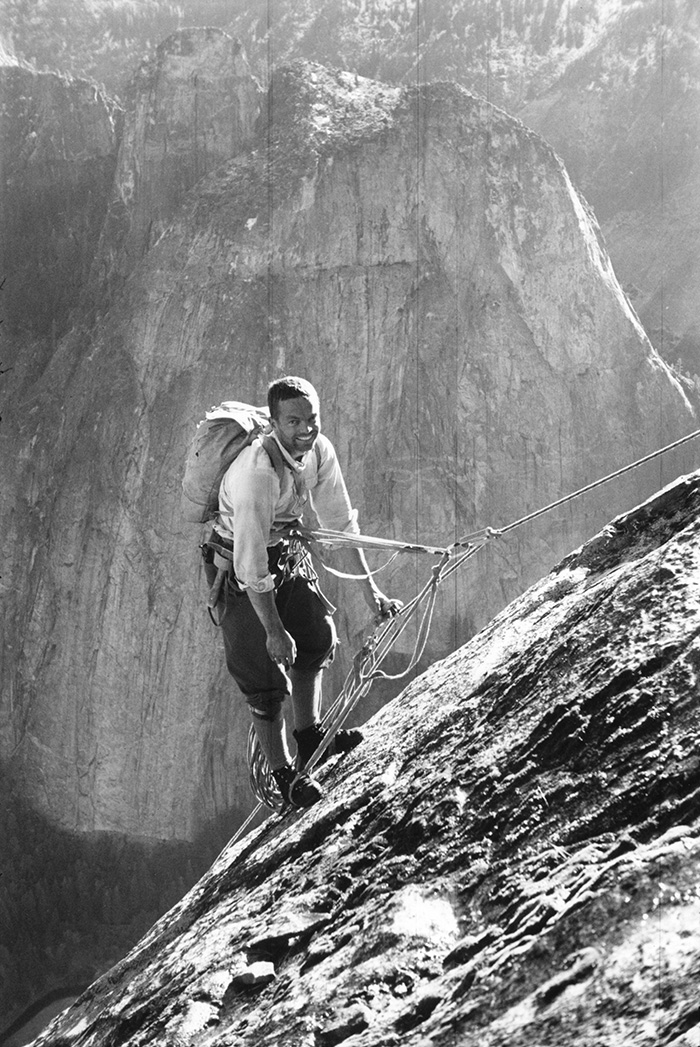

Frost during the second ascent of the Dihedral Wall, June 1964 (Royal Robbins).

Unknown Yosemite climbing pioneer showing the construction of a carabiner break rappel used for descending a rope.

Read other articles by Chris Van Leuven here.