- Death Valley’s Battle With Climate Extremes - 01/01/2024

- The Future of Homewood - 12/05/2023

- Kula Cloth - 10/18/2023

Exploring Northern California’s big trees by bike and on foot

Words and photos by Leonie Sherman

Hiker biker camp in Jedediah Smith State Park.

WHEN DOES THE FOG ROLLING IN OFF THE COAST become mist and when does that mist become drizzle? How big do the droplets need to be before it’s full on rain? And at what point on that spectrum does an unprotected camper need to seek shelter? These are the questions that ran through my mind as I regained consciousness in a soggy sleeping bag just north of the California border, at the start of a weeklong hike and bike journey through Del Norte and Humboldt Counties.

In one hundred miles between Brookings, Oregon and Arcata, California, there are four state parks, three county parks, two state beaches and one national park. Miles of hiking trails wind through neck-straining groves of ancients trees, to hidden waterfalls and windy overlooks, past carpets of wildflowers. The nation’s largest lagoon system is bordered by stretches of deserted beach that fade into fog and towering trees. Single tracks and secondary paved roads provide scenic alternatives to Highway 1. You could bike the entire distance in a single day. My friend Tanya and I took five. We were interested in making memories, not miles.

Along this stretch of rocky steep coast, studded with sea stacks and intersected by broad rivers, there are a hundred words for precipitation. But that moisture burns off every day, leaving bluebird afternoon skies and awe-inspiring sunsets. Cool temperatures provide the perfect conditions for riding, or hiking, or an afternoon yoga session, or lolling on a deserted beach. Sunblock won’t be a concern. And those gloomy summer mornings allow giants to thrive.

Ancient redwoods grow from the extreme southwest corner of Oregon to Monterey County, in a thin strip of temperate terrain almost 500 miles long and five to fifty miles wide, never more than 2,500 feet above sea level. A single tree can drink over 100 gallons a day. In winter they are nourished by torrential rain; last year Humboldt County recorded over 150 inches. During dry summer months they rely on coastal moisture — their uppermost needles can pull the stuff right out of the sky so they don’t need to transport it hundreds of feet against gravity.

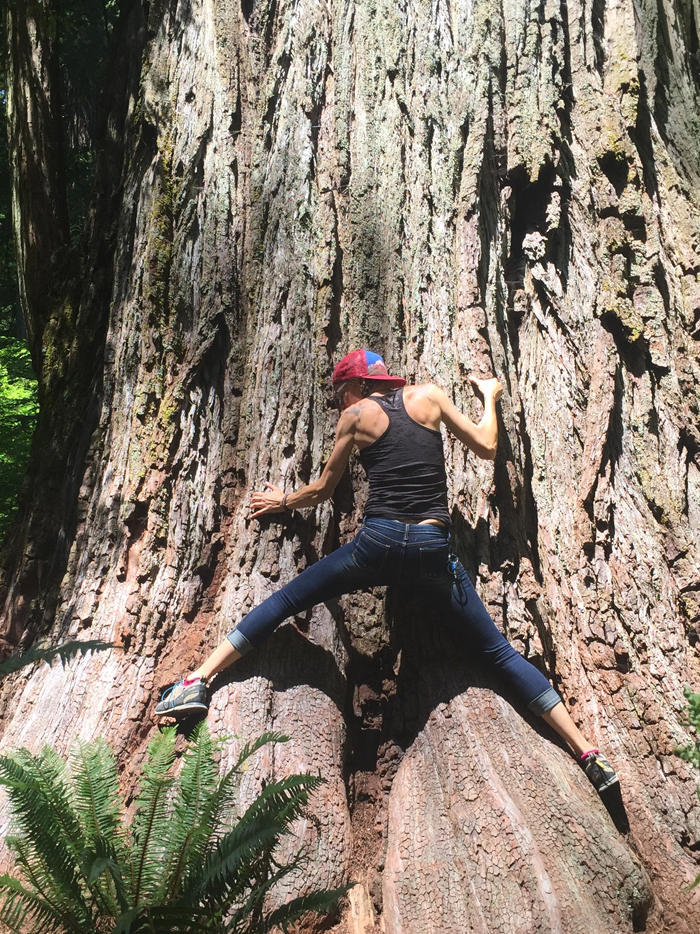

Après lunch boulder traverse of an old growth (Tanya Stillerg).

They are the oldest and tallest trees on the planet, living over 2,000 years and growing almost 400 feet tall. Fossil records indicate they’ve been around 170 million years, when their range covered much of Europe and Asia. Before the gold rush invasion — just 170 years ago — Sequoia sempervirens, the ever-living giant, occupied about two million acres along what is now the California coast. Less than 5% of that remains today. Most of the protected 110,000 acres of old growth redwoods left on the planet are in Humboldt and Del Norte Counties.

The mild climate and abundant moisture of these counties also allow humans to flourish. The regions original inhabitants, the Yurok, lived in permanent villages along the coast and the Klamath River for thousands of years before European contact. They maintained balance through good stewardship, hard work, wise laws and constant prayers to the Creator. Their traditional ceremonies brought neighboring tribes together in seasonal celebrations. The arrival of Europeans brought disease and massacres. By 1910, only about 700 Yurok survived on the reservation bordering a 44-mile stretch of the Klamath River. Despite poverty and lack of basic services the tribe is enjoying a resurgence and recommitment to sacred traditions. Today nearly 5,000 people are enrolled in the Yurok tribe and it’s the largest Indian tribe in California.

Our journey began near the northern boundary of their ancestral territory. Jedediah Smith Redwood State Park, 10,000 acres of fern draped canyons and old growth, lay about 25 miles to the south. Smith was a profit-driven fur trapper known for murdering natives and general surliness. In 1826 his party of explorers became the first white men to reach California overland. Six years later he disappeared while scouting for water; his company learned he had been killed by Comanches in what is now Kansas. As the miles rolled away beneath our tires, Tanya and I passed harbors, beaches and rocky headlands. We watched gulls wheel overhead and savored a panoramic vista where river and ocean meet before reaching the bustling metropolis of Smith River, population 866.

Just south of town we left the coast and turned east to follow a short section of the longest undammed river in the state. The Smith River carves a broad swath past steep canyon walls through dense forest along highway 197. We paused to loll on the beach and contemplate the emerald pools at the 50 acre Ruby Van DeVenter County Park. Ruby was a botanist who collected over 4,000 specimens of native plants from the wilderness around her Del Norte homestead. Her contributions to understanding the flora of this area are legendary and the idyllic park named after her hosts a few campsites and a lovely picnic area.

Hiking among the ancients is a humbling experience that inspires reverence.

At the entrance station to the state park we paid $5 each for a hike and bike camp site, situated far from the rumble of generators at the $35 sites in the main campground. Campgrounds along this popular section of coast can be booked out six months in advance, but a biker or backpacker can often find a site the same night. Our spot was nestled beneath towering ancients, a three minute walk from the placid river. All the folks you want to meet are hanging out in the hike and bike campsite; our nearest neighbor was a Finnish vegan adventure writer hitch-hiking the coast solo before section hiking the Pacific Crest Trail.

After dinner, a stroll through the forest brought us to the edge of the river. We hiked along the rocky beach past psychedelic driftwood to the main campground and the evening campfire presentation, where we learned about Doug Fir loving tree voles, the Humboldt flying squirrel, the corvid invasion of old growth forests (they’re attracted by the lure of easy food that accompanies increased human activity) and the endangered marbled murrelet, a football shaped puffin relative that nests high in the canopy of old growth trees. When our brains were full and the sun had set we stumbled through the darkened forest to a peaceful slumber at the feet of giants.

The next day we biked east on Highway 199 to an interpretive trail along Myrtle Creek, a serpentine hillside draped in magenta rhododendrons, fragrant western azaleas, pale irises, sticky monkey flower and foxglove. Another hour of riding brought us to a short loop hike through an ancient grove and the perfect spot for a picnic lunch. Our days fell into a relaxed rhythm of riding and hiking, dirt roads and single track, meandering trails, crumbling golden cliffs, enchanted waterfalls, deserted beaches and brackish lagoons. Every night the roar of crashing waves lulled us to sleep. Every morning the lilt of fluted birdsong brought us back to the world. We reached Arcata grateful for a restaurant and a bed, but already plotting the next redwood hike and bike extravaganza.

Hiker biker camp at Gold Bluffs, Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park.

Biking the Streelow Creek Trail, Redwood National Park.