- Paddling My Own Canoe - 10/01/2018

- West Coast Board Riders Club - 10/01/2018

- Never Too Oldfor Gold - 07/29/2018

Alpinist and author Isabel Suppé reflects on the accident that changed her life

By Haven Livingston

In July 2010, Isabel Suppé was climbing the 17,561-foot Ala Izquierda in Bolivia’s Cordillera Real, when her partner, Peter Wiesenekker, slipped on a patch of ice. Gaining speed, the fall ripped out their anchor and they both tumbled over 1,100 feet down the face of the mountain. When they came to a stop, both alpinists had broken bones. With injuries and extremely cold temperatures, death seemed unavoidable.

But Isabel persevered and tried to get help for both her and Peter by crawling across the glacier. She survived the first night by sitting on one tiny piece of exposed rock so her clothes wouldn’t freeze to the glacier. She leaned her head onto a trekking pole in a way that would wake her up should she start to fall into a deep sleep.

The next day she knew she wanted to live, had to live, and would do anything to get herself off the mountain. Though her leg was broken and her foot crushed, Suppé spent the next 48 hours dragging her broken body across the glacier. The rescuers who found her were amazed that she was alive. Sadly, Wiesenekker didn’t make it.

When Suppé describes Starry Night, the book she wrote after the accident, many readers expect another Touching the Void story. While there are some similarities—Touching the Void plays out in the nearby Peruvian Andes—Suppe’s account is unique. More than just a climbing accident narrative, Starry Night dives deeper into the author’s life before and after the fall.

The book’s title is taken from the painting that Van Gough created while looking through his insane asylum window at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Suppé relates to being trapped in the hospital, and tortured by pain while finding a sense of freedom in the beauty of the outside world. “Even when I thought I might die on the mountain, I remember staring up at the stars and feeling deeply moved by their beauty,” she said.

Though Suppé claims that her passion for climbing spontaneously boils up from within, it’s likely that her greatest influence was her grandfather. After the Second World War, he walked from the Black Sea back to his native Germany because he wanted to be in the mountains again. When doctors gave him one year to live after being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease at age 50, he kept on climbing, and lived to be 78. He died shortly after he found himself unable to put on a harness and tie into a rope.

Suppé was clearly cast in the same mold. Her life’s meaning has evolved in the mountains, particularly when she moved from her native Germany to the Andes of South America.

Working as a translator and a mountain guide, Suppé supported herself by living on the fringe. In the book she cites examples of giving up on worldly possessions to fund “one more climbing trip.” Gazing out her window one fall afternoon in Bolivia, she contemplates the refrigerator she had been saving up for and realized that with winter coming soon, she could store her food outside. Predictably, she used her refrigerator money to fund another trip to the mountains, proof that climbing provided more sustenance to her than food.

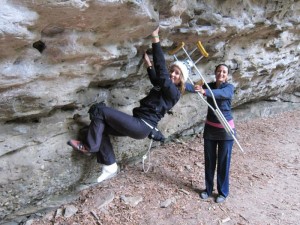

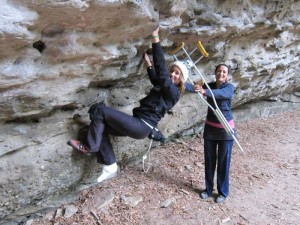

In describing life after the accident, she recalls being incredibly saddened by what she saw in the hospital. “I had fought so hard for my life, and people lying around me in the hospital were just waiting for death in total apathy,” Suppé said. Inspired to climb more than ever, just over a month after the accident she set out with her crutches to climb Argentina’s Nevado de Cachiit, and was the first woman ever to solo the peak. Doctors had predicted she would never climb again.

One year after the accident and still on crutches, Suppé and partner Robert Rauch established a new route up the technical and steep southwest face of Serkhe Khollu, in Cordillera Real. They named it the Birthday of the Broken Leg.

Today, Suppé is in the process of riding her bike across the U.S. in an effort to raise funds for a surgical procedure to her right ankle. Without the surgery, she will never walk again without crutches. Planning to reach New York on September 29th, cyclists, runners, climbers and other outdoor athletes will join her as she crosses the George Washington Bridge.

As for her climbing goals since the accident, Suppé says, “I haven’t changed a thing.” But for now, her focus is on getting mobility back to her foot and on finding a publisher for an English version of her book, which is currently only available in Spanish.

Learn more about Suppé’s fundraising and travels at www.isabelsuppe.com.