- Tahoe’s Nevada Beach Tops the List of Hard-to-Book Campgrounds - 07/17/2024

- Cannabis Watershed Protection Program Cleans Up Illegal Grow Sites - 07/10/2024

- French Fire - 07/05/2024

With the lower Corral Trail, TAMBA creates a win/win for Tahoe freeriders and land managers

By Rick Gunn

The year was 2008. I had just returned back to my home in South Lake Tahoe after a three-year bicycle tour around the world. I faced the usual readjusting to day-to-day life, but there was one profound irony I hadn’t anticipated: my mountain bike skills had pretty much dropped to zero as a result of spending years on a road bike.

So I did what any fat-tire cyclist would do, and that was grab my full-suspension mountain bike and put rubber to the dirt. Destined for a familiar stretch of single-track off Oneidas Road, I huffed up the steep pitch of pavement, intent on regaining my skills while riding an old friend: the Corral Trail.

Giddy with anticipation, I heard a rumor that the U.S. Forest Service built a new set of trails in the area while I was away. When I approached a gleaming new signpost at the top of the Corral trailhead, my heart hummed like a knobby tire on asphalt.

Studying the sign, my eyes scanned a strange new set of trails: Armstrong Pass Trail, Armstrong Connector, and an odd-looking squiggle off the side of Corral Trail named Sidewinder Trail. Together these new trails created eight additional miles of luscious singletrack from the top of Armstrong Pass down nearly 3,000 feet to Oneidas Road.

The effect was Pavlovian, and it was enough that I pedaled another hour uphill from my usual descent starting point until I reached the top of Armstrong Pass. Then, for the first time in three years, I unlocked my suspension and dropped in. What followed was a two-wheeled communion.

For the next 45 minutes, I was a blur across the mountainside, sweeping across the Armstrong Pass trail and its wide, swoopy turns. Linking with Armstrong Connector, the trail dropped steeply as I squeezed through a group of granite boulders, then through an orchestra of steeper rocks.

Corral Trail began where Armstrong Connector ended, and it quickly forked into Sidewinder. Pitched perpendicular through tightly banked turns for several miles of bliss, I eventually returned to Lower Corral, where the trail crescendoed over a carnival of bumps and jumps to its terminus. Religion.

Trail stewardship in Tahoe

I had just experienced a whole new era in the evolution of Tahoe mountain bike trails, but how did this happen in the time I was away?

These trails were more fun, faster and more challenging than anything that I’d previously ridden, but they also incorporated state-of-the-art trail design technology that kept them environmentally sustainable for future generations. Only later would I learn that the trails were the result of a unique collaboration between the Forest Service and Tahoe Area Mountain Bike Association (TAMBA), a local mountain bike advocacy group.

This unlikely partnership was conceived 20 years earlier.

In 1988, legendary South Lake Tahoe athlete Gary Bell joined forces with North Lake Tahoe’s Kathlee Martin and created the grassroots organization TAMBA, the first of its kind in the Lake Tahoe area. Before long, it enlisted 1,200 members and recruited volunteers for trail maintenance. As the first group to give Tahoe mountain bikers a voice, it combated a growing wave of trail closures that were already occurring in other areas, including Marin County.

Roughly a decade later, Dave Hamilton, an avid mountain biker and college educator, inherited TAMBA. He followed in Bell’s footsteps in organizing local rides and working with the USFS. Eventually Hamilton accepted a college administration job outside the area, and TAMBA entered a period of dormancy. It was around this time that Tahoe’s trails were threatened, mostly because of the rise of the freeride movement.

As everyone knows, this style of riding began in the north shore of Vancouver, then was emulated throughout North America. This movement led to a sharp rise in illegal trail building within the Tahoe Basin. It was only after a local free rider crashed on an illegally-built jump—-and had to be Care-flighted out for his injuries—that the forest service began to shut down illegal trails.

“We were seeing a lot of unauthorized trail construction being built around that time,”

explained U.S. Forest Service Trails Engineer Jacob Quinn. “There were a lot of illegal jumps being built out in the woods, and we were spending thirty, forty, maybe fifty-thousand dollars a year to go tear down illegal trails or unauthorized features. It became clear to us then that there was a need for more mountain bike trails, and more bike specific skill-building features on public land.”

This prompted Quinn and others from the Forest Service to hold a series of public meetings in collaboration with IMBA. One meeting attracted more than 70 local mountain bikers. Quinn suggested that freeriders stop building illegal trails and also find someone to resurrect TAMBA. Only then, Quinn said, would the forest service consider working with TAMBA to build legitimate, authorized and sustainable trails with features and jumps.

TAMBA responds to the need for better trails

From out of those meetings came the reemergence of TAMBA as it gained a new leadership board including Ben Fish in South Tahoe. A former downhill mountain bike racer and professional landscape architect, Fish was a natural for the job. Assisted by his wife, Amy Fish, TAMBA quickly organized an aggressive schedule of trail workdays, which drew several dozen people because, in Fish’s words, “We try to make them fun. We provide volunteers with food and drink after each trail work day, as well as throwing parties and holding events in the times between.”

TAMBA didn’t stop there. They encouraged input and recruited volunteers and helped the Forest Service build and maintain several new trails in the Tahoe Basin, like the Monument

Pass Trail, currently under construction.

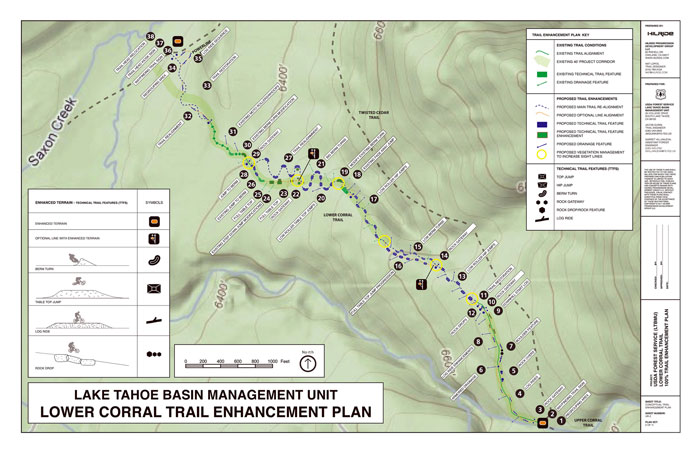

TAMBA has since turned their attention to the lower section of Corral Trail. Recently, Fish and the Forest Service agreed to work with a professional trail building company to rework the entire area. The new plan includes between 30 to 35 more features: tabletop jumps, hip jumps, berm turns, log rides, rock drops, as well as rock gateways. All this, however, requires money.

Having narrowly lost out on a $30,000 trail grant from Bell Helmets, TAMBA was approached by another avid Tahoe Mountain biker, Erik Christenson, who works as a Senior Account Executive with the Salesforce Foundation. Christenson agreed to match donated funds up to $15,000 to recover the $30,000 from the lost grant.

TAMBA has raised $6,000 and hopes donors can raise another $9,000 to complete the work. The money will be used, among other things, to rent a mini-excavator, machinery, buy tools, feed and fuel volunteers and pay the fee of the professional trail builders.

“When it’s done it’s going to be great,” Fish confides. “It’s going to be kinda’ like a bike park, stretched-out along a mile.”

Besides donations, Fish is always recruiting new members. When I asked him where he envisions TAMBA and Tahoe mountain biking in the future, he paused to reflect.

“With all these new trails, there’s a lot more variety of riding out there. And people around the country, and around the world are beginning to recognize Tahoe for what it is—a mountain bike Mecca.”

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

You can join TAMBA by going to www.tamba.org. Costs are $20 for an individual membership and $30 for a family. Members receive a newsletter and access to the website for trail workdays, events, and the latest projects and trail news, as well updates on local trail conditions.