- Tahoe’s Nevada Beach Tops the List of Hard-to-Book Campgrounds - 07/17/2024

- Cannabis Watershed Protection Program Cleans Up Illegal Grow Sites - 07/10/2024

- French Fire - 07/05/2024

Challenging and remote, the Cal Salmon offers some of the best rafting in the country

Story and photos by Rob Dunton

A kayak doubles as a lunch buffet.

Six Rivers National Forest, Siskiyou County – Six taut inflatable rafts in bright, kindergarten blues and yellows lined the banks of California’s Salmon River, often referred to as the Cal Salmon to distinguish it from the more famous but less challenging river of the same name in Idaho. Contusion, the first batch of Class III-IV rapids boiled a thousand yards down stream. Helmets on, life preservers cinched tight, our paddling skills reviewed and tested, we pushed off into smooth blue-green water.

“Hard right!” called out Diego Valsecchi, our Argentinian-born rafting guide and Italian-grandmother schooled chef, from his perch on the back of the raft. Our team of six paddlers responded to his command – three on the left powering forward, three on the right digging their paddles in and back paddling hard off their hips. The boat turned sharply on cue. We were on.

Alex Nicks, one of our safety kayakers, paddled past with quick strokes to position himself below us. Gliding by in his bright yellow kayak, he shouted back in his waggish British accent: “No bobbing cherries in this frosty margarita, all right mates.” Translation: staying in the boat would be a good thing. A native of the UK, Alex is a European kayak rodeo champion and hosts his own series of thrill-packed kayaking videos.

As I would discover over the course of the weekend, the resumes of our unassuming, bohemian guides from Truckee-based Bio Bio Expeditions were impressively diverse: Diego, the eldest of 11 children, grew up on an Argentinian ranch where he helped raise polo ponies and became one of his country’s finest kayakers. Laurence Alvarez is the past captain of the U.S. Rafting Team. Kipchoge Spencer is a graduate of Stanford’s Earth Systems Program (combining environmental sciences and economics) and a talented musician. Marc Goddard is a former history teacher. Ryan Allred holds a master’s in Environmental Science and was U.S. Rafting Team captain and champion in 2000. Together, they had hundreds of thousands of river miles among them.

Diego dug his steering paddle deep into the churning water and spun the boat to get us into final position. “Back paddle!” he shouted over the din of the thrashing river. The river had turned from a moving mirror of greens and blues into a stampeding roller coaster of white foam. Waves blasted over the bow of our raft. Our crew of father, son, friends and girlfriends bent forward and pulled hard through the surf, laughing, howling and grunting with each stroke. In a matter of seconds, we were through. The waters calmed, we smacked our paddles above our heads – the rafters’ high-five – then spun to watch the next raft shoot the rapids. Pumped and exhilarated, we paddled with paced, powerful strokes toward our next conquest: The Narrows.

The day started leisurely. Eighteen guests awoke in tents nestled in a tree-lined meadow to the smell of coffee, chai and breakfast: scrambled eggs with sautéed onions, tangerine and cranberry coffee cake baked in a Dutch oven, chorizo sausage, fresh fruit, yogurt and quesadillas. Most of the guests had arrived the night before, many after dark. After chow, we circled around the campfire and played an entertaining name game. We would be family for next four days, and it was time to meet the relatives. Each person, guides included, introduced themselves with a memorable moniker and body motion which was then repeated by the entire group.

“I’m R-r-rob the wr-r-r-iter,” I said rolling my R’s in my best Shakespearean drawl, with a bow. One by one, the group mimicked my intro. Ben the Frenchman. Fancy Nancy. Laurence of Arabia …

With our newly forged nicknames branded into our brains, we were fitted for life vests, wetsuits and paddle jackets, and headed for the river.

On our first rafting day, we rode in vans to Butler Creek for easier, intermediate-grade rapids (class III and IV). Even at high noon, shadows were constant companions at the bottom of the sculpted granite gorge, cut deep into the Marble Mountains. The crystal clear river, which received National Wild and Scenic River status in 1980, is un-dammed and cold, flowing freely from the snowmelt of the adjacent Trinity Alps.

After successfully maneuvering through The Narrows and Gaping Maw (class IV), we floated into a calm, deep pool flanked by a stunning waterfall. We tied our rafts on the cobbled shore and the staff unloaded waterproof boxes and duffle bags packed with lunch. Kayaks were flipped onto their bellies and became instant buffet tables. Chef Diego sliced veggies, and spread out pita and sandwich fixings of all kinds. Some of us shimmied out on a rock ledge and leapt off into the deep pool. Others peeled down their damp wetsuits and relaxed in the warm sunshine.

Ryan Allred, who lives in the area year-round, told us tales of the Karuk, the Native Americans who first lived in the area, and of the miners and settlers who arrived in the mid-1800s. A bit of California’s gold rush history lives on. As we went downriver, Ryan pointed out metal hasps and anchors drilled into granite walls and boulders. When the rafting season dies down in July and August, a few hydraulic, dredge-mining systems are hooked in and scour the river bottom for placer gold and platinum. The nearby towns of Happy Camp, Sawyers Bar and Forks of the Salmon were rowdy mining towns in their hey day. The area is also notable for another reason: Legend has it that Big Foot, or Sasquatch, has been sighted more often between Happy Camp and Willow Creek than anywhere else.

As we neared the end of the day’s rapids, we collided with California’s second longest river, the Klamath (at 250 miles, only the Sacramento River, 382 miles, is longer). A small island peaked in the middle of the confluence of the powerful rivers. “The Karuk call it Ishi Pishi Mountain,” Ryan explained. “Ishi Pishi in their native tongue means ‘end of’ since both rivers end their separate lives here, then join together as one. For the Karuk, it is the center of their universe, a very spiritual place.”

We pulled out after running Big Ikes on the Klamath, a series of class III and IV rapids less than a mile past the confluence.

Back at camp, a massage room had been set up on the fringe of the meadow, enclosed in mosquito netting. As weary paddlers placed themselves under healing hands, Matt Stevens, 16, played Frisbee with his father in the dusk light. A campfire glowed next to our dining tables, which had been decorated with candles and colorful Guatemalan cloth. Wine, grapes and cheeses held us over as Chef Diego crafted a dinner of pan-roasted salmon with basil, tomato, parsley and olive oil; plus steak, grilled tofu and mushroom kabobs; and a hearty salad. For dessert, we were treated to chocolate brownies baked in the Dutch oven.

After dinner, guide/singer/song-writer Kipchoge Spencer brought out his guitar. Isaac James, his bongo-beating sidekick, joined in, entertaining us with his own passionate, satirical tunes beneath the stars. A full moon rose slowly above the trees and canyon walls, illuminating the meadow and turning the Cal Salmon into liquid silver.

The music had drawn guides from other outfitters to our camp, and when the last guests retired to their tents, these kayak junkies grabbed their boats and headed to the river. They paddled downstream to one of the river’s perfect surfing spots: an endless wave formed by a submerged boulder, creating a churning hole of circulating water. For the next two hours, illuminated by nothing but moonlight, the river brethren took turns riding, spinning and flipping in the curl.

When day two dawned, we were ready to tackle what we came for: Class V white-knucklers. I asked Diego over breakfast what some of the names of the rapids would be that day.

“Well, first there’s Bloomer Falls, then others like Last Chance and Freight Train…”

“We’re going over a waterfall!” I interjected.

“Two, actually,” smiled Diego, mischievously.

We launched from Nordheimer Camp, within walking distance of our encampment. Paddlers were reshuffled from the previous day to balance the power and experience that would be needed in the class V rapids. As conveyed, our first challenge would be Bloomer Falls, a 10-foot drop through a cut in solid granite.

As we glided for toward the chute, we honed our paddling skills. Ben the Frenchman soothed our nerves by leading us into song, singing any tune we could remember the lyrics to. Below the fast moving surface, steelhead could be seen pushing their way upstream.

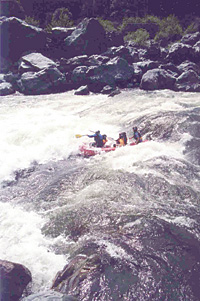

The safety kayakers raced ahead and got in position to pick up any swimmers. One by one, each raft got into position, then blasted through. The rafts pitched over the lip and weresucked into the frothy bowl below. Thoroughly soaked, we bounced like a toboggan careening down a mountain. Our guides, appearing no worse for wear from their moonlit kayak sortie, steered us confidently, making such a thrilling and potentially dangerous shoot appear reassuringly safe.

Below the falls, we realized one raft had suffered an irreparable gash. Its paddlers were distributed among the remaining rafts while the wounded beast was dragged up the cliff face to the adjoining road to be hauled back to camp. As the water raced, our pace quickened, weaving through a boulder field in The Maze, shooting 15 feet off Cascade Falls, bouncing through Achilles Heel (class IV+), Last Chance and the grand finale, Freight Train (both class V).

At the end of our thrilling run, we carried the raft to the trailer. I would have been happy to circle back and run it again, but the thought of dry clothes, a massage, and another of Diego’s gourmet meals made heading back to camp equally tempting. It struck me that this must be the ultimate challenge: to create camp life so rewarding that it competes head to head with nature’s playground. On the Cal Salmon, it had been done … and would be again.

Rob Dunton is a freelance writer/photographer whose work can be found inpublications such as National Geographic Adventure, the Los Angeles Times and Canoe & Kayak magazine.