- Exploring Lava Beds National Monument - 07/15/2024

- Wandering Through Washington - 03/21/2024

- Striding Through Socal Sun, Storms and Snow - 12/27/2023

The Postcard Thrills of Lost Arrow Spire’s Famous Tyrolean Traverse

By Matt Johanson • Photos by Chris Falkenstein

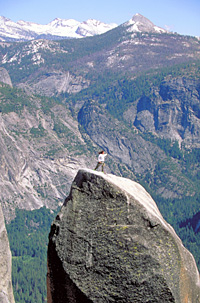

Getting back to the main cliff after climbing the Spire.

A striking pinnacle just east of Yosemite Falls draws adventurers from around the world. Reaching the summit of Lost Arrow Spire affords an awesome view of the park’s glacier-carved valley and takes no small amount of technical skill. But for once in this renowned climbing mecca, the climbing isn’t the story.

Lost Arrow Spire’s unique attraction is the maneuver climbers use to depart from the pointy granite peak: the celebrated “Tyrolean Traverse.”

To return to relatively flat earth, climbers anchor ropes to bolts atop the spire and also to a trusted pine tree 80 feet away on the valley rim. Locking themselves securely to the rope with carabiners, they step into the abyss and pull themselves hand over hand along the rope to the pine, a dramatic scene pictured on many Yosemite postcards.

Leaving the security of solid rock for the thin air of the chasm makes even hardened climbers cringe. Alternatively, a handful leave Lost Arrow by simply rappelling back to the spire’s notch and rock climbing up to the tree, a slower return that employs more common skills.

“But the Tyrolean is just so cool,” said one climber, explaining the traverse’s popularity.

Some scale the spire from the valley floor as an all-day or overnight effort, but most climbers hike up the Yosemite Falls Trail to the valley rim and rope up at the pine tree. That’s the route my partners and I took when climbing Lost Arrow on two occasions. The hike gains several thousand feet and takes at least two hours in each direction, so an early start to the outing is advisable.

A small island in space looking west from the Spire.

The climb begins with a 275-foot rappel into the spire’s notch. Descending this distance requires either two climbing ropes tied together or one exceptionally long rope.

From the notch, climbers use a second rope to ascend the spire, dragging the first line from the pine tree in tow. This first pitch features climbing rated at 5.10d, a level many gym climbers attain but which carries an entirely different meaning when leading 3,000 feet above the valley floor.

Atop the first pitch is the Salathe Ledge, named for pioneer climber John Salathe, who first climbed the spire with his partner Ax Nelson in 1947. The ledge is commodious enough to allow several climbers to sit comfortably. With its grand sweeping valley views, this is one of the world’s most spectacular lunch spots.

If you go, take advantage of it. You’ll need a good lunch because the next pitch is a killer 5.12d. The altitude and exposure magnify the difficulty, so everyone besides world-class climbers had better just forget climbing this without aid.

I lead this section on my second ascent, and though it’s fairly tame for good aid climbers, I found it airy and scary. Aid climbing is not my forte. Placing my weight entirely on my gear and the occasional bolt, I nervously pushed upward. On lead at that height, the slightest breeze felt like a gale, and every squeak produced by the bolts, gear and my shifting weight stopped my heart cold. “Super scary exposure,” I wrote in my guidebook that night.

After I reached the top, I secured the line for my partner Sean to follow. In no time at all, we stood together atop the spire, the first party of the day to summit. But what about the second team of four climbers following us? The sun was setting and they were nowhere in sight.

“We’re the only ones who will make it today,” Sean said. “That other party behind us just popped a bolt.”

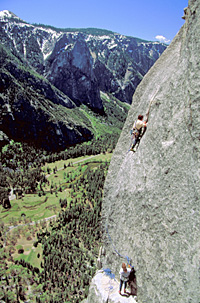

Some fierce free climbing (or somewhat easy aid climbing) leads to the top.

Though a rusty bolt had held for me, the next climber’s weight ripped it from the rock, dropping him into a 20-foot fall. He wasn’t hurt, but their team had to retreat back the way they came. Until somebody replaced that bolt, climbing the featureless rock face it protected would be much harder and more dangerous.

Thankfully, seven bolts were available atop the spire to secure our ropes for the traverse back to the tree. Taking no chances, we utilized them all as we departed the spire and crossed the chasm using a variation of the Tyrolean technique. We reached the rim in time to see the alpenglow on the snowy peaks fade to darkness.

We donned our headlamps for the long walk back to camp, still glimmering with our own internal alpenglow from our day of postcard thrills.