- Tahoe’s Nevada Beach Tops the List of Hard-to-Book Campgrounds - 07/17/2024

- Cannabis Watershed Protection Program Cleans Up Illegal Grow Sites - 07/10/2024

- French Fire - 07/05/2024

By Doug Robinson

Short pants and sunny High Sierra granite on the East Buttress of El Capitan, with a sweeping view of the Cathedral Rocks from the belay; this is as good as it gets.

Photo: Karl Bralich

“Best Of” lists are bogus. Or at least suspect. In Jack Kerouac’s Sierra climbing novel The Dharma Bums, the Gary Snyder character puts it that “comparisons are odious.” Which is better anyway, Half Dome or El Cap? See what I mean?

Even so, as much as I revel in the uniqueness of every climb, I once found myself playing a “best of” game as I drove across the country: Find the best 5.6 climb anywhere. The Great Arch on Stone

Mountain in North Carolina had perfect rock and a tree for each belay. But pitch after pitch most of the moves were the same. Classic, but all liebacking. Last of the Good Guys on Quartz Mountain, Oklahoma, had tremendous position, snaking through a much harder headwall, with bomber bolted belays. But it was a taste harder at 5.7. Nearly home, I found it: The Tree Route on Dome Rock in the Needles of the southern Sierra. It flows from face climbing to jams to liebacking to friction. And everyone gets to make their own anchors.

Yes, the High Sierra. It’s hard not to be a chauvinist about our great weather and sparkling granite. If I’m not careful, I catch myself raving about “the finest mountain range in the world.”

It’s also hard to choose just ten climbs. Worse though, it feels downright scary to me to put out recommendations so anonymously. Sure, I know the terrain. I’ve been guiding in the Sierra for nearly 40 years. I’m constantly recommending climbs to clients and even to strangers I meet on approaches. My function as a guide, I like to say, is to make myself useless. Trouble is, those guys I can urge onward after checking their moves, watching them build anchors and test holds. Or at least ask about their relevant experience and look them in the eye.

But you there, dreaming through this list on the couch: it’s impossible to summarize the pitfalls – many of them deadly – of trad climbing in the wilderness. Just don’t forget, if you please, that humility is worth its weight in cams, and that gravity is very democratic. For a rule of thumb, if you back off two number grades from what you lead trad climbing outdoors (sport leading doesn’t count, and gym leads are totally irrelevant here), then you’re getting into the ballpark of what you might reasonably step up to on a thousand feet of unknown rock, at altitude and with occasional runouts, hidden looseness, the wind rising and clouds starting to build over your shoulder. Did I mention that your partner has turned silent and no longer feels like leading? It’s on you now. As they said in The Right Stuff: “Work the problem.”

So let’s just call this list some of my favorites. As a guide on the lookout for “teachable moments” I arranged these climbs to lead you gradually into the art of mountaineering on High Sierra peaks. I hope you enjoy the journey.

Enough. Get out. Go wild. Live your adventure.

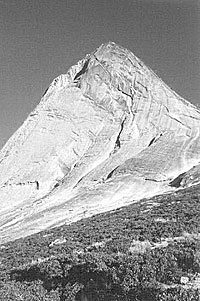

Russell’s East Ridge.

Photo: Bob Burd

Mt. Russell East Ridge: Class 3

Let’s start on Third Class, and go right to the head of the class with Peter Croft’s favorite third class climb in the High Sierra. It is ultimately cool that this guy with the skill and huevos to make the first solo ascent of Astroman (5.11c), this guy who is simply overflowing with the sheer animal joy of moving over stone, would move on to the Sierra’s alpine zone for the next phase of an astonishing climbing career. But there he is, if we catch sight of him at all, romping over jagged peaks. Peter says this is the best third class in the Sierra, so go do it. And take a rope. Classic wit defines third class as “you can probably stroll up this with your hands in your pockets, but you’d better take a rope along just in case.” Any change in weather, darkness, or even

the attitude of your partner can make you mighty glad you did.

Matterhorn Peak, North Gully: Class 3

Still third class, but with snow. So add an ice axe to the rope. And a few runners and nuts to belay from the granite walls of the gully. And take a quick snow climbing lesson (Sierra Mountain Center in Bishop is very good). You’ll be glad you learned the hot tricks, and once you are snow-proofed the alpine zone really opens up. For a literary spin, get a copy of Jack Kerouac’s classic The Dharma Bums as your guidebook. It’s so faithful to the terrain that you can actually stumble over rocks in the terrain just where you trip onKerouac’s prose. And those “free

bhikku” alpine Buddhists of Kerouac’s “rucksack revolution” will point you to a revitalized vision of the West.

Bear Creek Spire.

Photo: Chris McNamara

Bear Creek Spire, NE

Ridge: II, 5.5

Norman Clyde soloed this first ascent back in 1932 and called it fourth class. Now it’s rated 5.5. Both are right. Classic mountaineers like Clyde were really that good. And belays on his era’s hemp ropes had their limitations. So classic fourth class has become one of those ratings with a built-in sandbag: bring a rope, a light rack (with lots of runners), your helmet and maybe even rock shoes. Clyde did. He and his buddies Jules Eichorn and Glen Dawson had special tennis shoes, fitted tight with the insoles ripped out for sensitivity. Sound familiar?

Mount Conness West Ridge: III, 5.6

Yes, I skipped Cathedral Peak. So crowded, and it was already on your list anyway. The west ridge of Conness is like two Cathedral Peaks stacked on top of each other with no traffic. Finding the rope-up is a bit confusing, so pay attention. DON’T approach it from Saddlebag Lakes: too long, too vague, and you end up climbing the peak twice for a pretty long day. DO backpack in from Tuolumne to Young Lakes (get a wilderness permit), and camp a mile beyond them toward the beautiful south face. DO linger a second night after your climb. That way you can truly savor the incredible fourth-class pitches that ride the edge of the south face, and enjoy the best views of the Cathedral Range on your hike out.

View of the Matthes Crest ridge.

Photo: Cathy Claesson

Matthes Crest Traverse

South to North: III, 5.7

As a teenager it took me three tries to finally pull off the traverse of Matthes Crest. I was proud of what a long route we had done. The climbing is not too bad on average, but at times it is wildly exposed, and there is plenty of rope handling to tangle you up. And there’s a surprising amount of route finding for a line you could summarize as, “It’s a ridge, stupid.” In particular, getting down off the fin at the very north end of the route seems to foul people up. So this is a good climb to work on staying found, hustling along, and ropehandling – in other words, all the stuff that will carry you onward to bigger alpine climbs.

Half Dome Snake Dike: III, 5.7

The best route on Half Dome is kind of scary. The crux 5.7 is fairly well protected – not wonderful, but OK. It’s the 5.4 you’ll be sweating. Several runouts go 75 feet, with no chance of extra pro. Nothing to do but suck it up and place each foot with care. The Dike shoots hundreds of feet up a smooth and crackless face that would be seriously harder but for this weathered protrusion, scooped and whorled with friction pockets that are solid enough without ever getting really positive. At times the dike is merely a foot wide. Read Steve Roper’s account on the Supertopo website of his second ascent (with extra bolts) for the entertaining story of how this climb came into existence.

Charlotte Dome

Photo: Bob Burd

Charlotte Dome South Face: III, 5.8

You will get lost on this climb, and it won’t matter. Everyone seems to have a favorite way to describe how to find your way up this massive wall with few prominent features. Don’t worry, there are many ways to go on the finely sculpted orange granite. You won’t know quite where you are, but you’ll get there. The only really sorry group I’ve heard about was climbing right at its limit, wandered way to the right, where they endured a gripping bivy. It is rumored that there is a loose rock on pitch #8, but this is unconfirmed. There is no choosing, either, between approaching it from the east or the west. You’ll want to come back anyway, maybe to climb Neutron Dance (III, 5.10d), and then you get to hike in the other way. I like to camp right at the base of the wall (good bear hangs on the wall – claws keep them from frictioning very well), which means going relatively early when melting snow patches save a long hike to the creek.

Temple Crag Venusian Blind Arete: IV, 5.7

This may be the shortest and easiest of Temple Crag’s Celestial Aretes, but it is not kindergarten. Think of its 14 pitches as a stepping stone to the world of longer, harder alpine ridges. Take your ice axe for the approach, climb efficiently, and watch for splitters. No, I don’t mean perfect cracks, though there are some. I’m thinking about fractured alpine granite poised to teeter off from the already-airy arete. Temple Crag is actually getting looser in recent years, and I wish I had space here to relate the story of the Atomic Broom, as unlikely as it is relevant. Since the millenium there have been several close calls and even two deaths, both on the Moon Goddess. STAY OFF of that ridge; I consider it too loose and no longer a rock climb. You will develop the fine art of testing every hold on the Venusian Blind, and probably like it enough to make plans to return for the 18-pitch Sun Ribbon (IV, 5.10a).

El Capitan East Buttress: IV, 5.10b

This is the way to climb El Cap: no hauling, no lines, no aid, no huge rack or extra water, no poop tube. The East Buttress comes equipped with fine climbing, great position, and has its ledges built-in. Don’t go too early in the season, though, when Horestail Falls is running just to the west. Every afternoon when the wind picks up it drenches the East Buttress. You don’t want to know how that would feel. You do want to sit up there in the sunshine, soaking up the inspiring view of classics from the Central Pillar to the Steck-Salathe.

Red Dihedral Incredible Hulk

Photo: Chris McNamara

Incredible Hulk The Red Dihedral: IV, 5.10b

Back in the seventies my friend Mike Farrell, who was on the first ascent of the Red Dihedral, dragged me up to the Incredible Hulk. We climbed a beautiful line on featured orange granite reminiscent of Charlotte Dome or the Salathe Wall that goes straight to the summit. It seemed like the shortest and easiest route on the face at III, 5.9, though we were climbing really well at the time. Neither of us wrote it down or drew a topo, and it was never reported anywhere. Now it has vanished. Of course it must be there, and every time I look at our photos I’m fired up to go back and find it again. But show me a photo of the right side of the Hulk, and I just draw a blank. So until I can retrace our sweet line from that long ago summer afternoon, I guess we’ll all have to make do with the Red Dihedral, on what Supertopo modestly calls “the best rock in

the High Sierra.” See you out there.