- Yosemite E-Biking - 01/12/2023

- The Yosemite Climbing Association - 09/01/2022

- Ryan Sheridan & Priscilla Mewborne - 05/17/2022

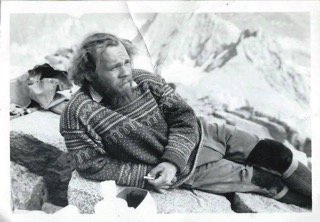

Professional climber David Allfrey

By Chris Van Leuven

Belaying on The Radiator, a cutting edge aid route in Zion National Park (Kristoffer Wickstrom).

From Patagonia to Baffin Island, Allfrey seeks out the most inaccessible summits in the world; retreat is his last option. We discovered what makes him tick and his biggest struggles.

The lashings started as the sun set over the Central Valley. It began as whips of water before erupting into a wild, gushing fire hose. All at once the 1,575-foot Horsetail Falls deviated from El Cap’s east flank and hit us with everything it had.

As we hung by climbing slings midway up the face that soggy March day eight years ago, winds swept across the Valley floor, smacking the wall below us and roaring up in a violent mixture of cottonball clouds and whistling air. We crawled into our hanging shelter, burrowed into our sleeping bags and waited it out until morning. That night, winds caught our hanging shelter and threw it around like a bronco bucking its rider.

“To this day that was the most terrifying night I’ve had on El Cap,” David Allfrey shares over the phone from his home in Las Vegas.

In the morning, as the sun rose behind Half Dome, we peered out of our hanging perch to see saturated black streaks cascading down the wall around us, pinching off and disappearing in the breeze. To me, the climb was over – I was too cold, too shell-shocked — but Allfrey shrugged it off and wanted to continue. “We would have gotten wet, but it wouldn’t have been that bad,” he later told me.

Since I’ve known Allfrey, now 33, I’ve rarely seen or heard him retreat off anything. Once he was a whisper away from the summit of Fitz Roy in Patagonia when a building storm forced retreat. He and Cheyne Lempe reached the deck when the clouds opened up; it didn’t stop raining hard for a week. Another time, he was smashed in the back by falling rock in Baffin Island, the injury forcing an immediate evacuation. Short of those times, he reaches the summit at most any cost, sometimes with world-famous Alex Honnold, other times with his closest friends or fellow members of The North Face climbing team.

What makes him stop and reflect, other than wild storms and falling stone, is the knowledge that as the years have passed more and more of his comrades have died in the alpine.

“I never said no to a big trip until now,” he told me in December. In recent months one friend died in a rappelling accident, one committed suicide and another suffered a severe spinal cord injury caused by a 120-foot fall. He had arrived home from a trip to the Cirque of the Unclimbables in the Northwest Territories, where he used rafts to float 250 miles down a river and completed the first ascent on a 1,000-foot tower (plus more feats), to a laundry list of bad news. “People were getting hurt in Yosemite. There was a huge rockfall off El Cap, and lots of death and destruction,” he said. “And once I felt like I had processed Hayden’s death [Hayden Kennedy took his own life after he and his girlfriend, Inge Perkins, were in an avalanche that killed her], then Neils Tietze died in Yosemite in a rappelling accident. Those all caused me to pump the brakes.”

Big pause.

He chokes up through the receiver. “That could be any of us. That could be me.”

Going Inside

That winter he moved his training and climbing circuits indoors where he could enjoy a homogenized, controlled experience, one free of sketchy rappels, stuck ropes, unstable cliffs and unpredictable weather. Day in and day out he’d get his work done, then hit the climbing gym, doing laps until his arms turned into jelly. He would also take his girlfriend out to dinner and generally play it safe. The whole time he thought about the friends that were no longer with him and “reflecting on where my heart is with it all.” Then the anxiousness crept in and he knew it was time to get going.

“I’m always in a state of planning and figuring out what the next thing is,” he says. “Because of that, I’m not always in the now.”

Then he got a call from seasoned expedition climber Paul McSorley, from British Columbia, who invited him to climb a first ascent big wall deep in the Colombian jungle with his friend Kieran Brownie. The two banged out their route in a fraction of the time they planned, despite climbing in 110+°F heat that made their skin melt, before heading to the next objective. Next they caught a bus halfway across the country to climbing area La Ventana (The Window), a limestone cave over a 2,000-foot waterfall. The night before starting up, they heard rumors that the routes were unsafe due to the protection bolts corroding in their holes. They took one look at the wall and the rusty bolts peppering the ceiling and turned around — it wasn’t worth it.

When I caught up with him soon after his trip, at the end of February, he was planning his next expedition, this time to Pakistan to climb Trango Tower in the Himalaya with members of The North Face team.

You can hear the intensity in his voice. And when he climbs, it’s with that same rhythmic, steady drive as when he talks, like a train. “Fast is fast, slow is fucked up and slow!” is his mantra, meaning if you never second-guess, just move, the summit will be reached. He doesn’t let go of the receiver until he knows plans are concrete, an action set. He’s like a Rottweiler clamping its jaw on a new toy.

Allfrey ascending fixed ropes in Baffin Island, June 2015 (Cheyne Lempe).

From Pacific Edge to the Himalaya

Allfrey’s parents started climbing in 1970 and introduced David to the sport when he was eight. Raised in San Jose, his youth consisted of frequent climbing trips to the Sierra with his family and learning his father’s trade of cleaning carpets and windows. His mother taught high school AP Chemistry. At 14 he began balancing work with the family business, school, and climbing, logging 12-hour days.

He enrolled at UC Santa Cruz keeping his feverish pace, adding big wall climbing to his repertoire in 2009, ticking off El Cap routes during long weekends with his mentor Scott Lappin. He also climbed daily at Pacific Edge climbing gym. After graduating, he worked as a substitute teacher, worked on Yosemite’s prestigious Search and Rescue team, and performed rope access work on wind towers before returning to the family business of washing windows and carpets.

In the near decade I’ve known him, he’s only gotten stronger and faster. In 2013 he and Alex Honnold made the first one-day ascent of El Cap’s Excalibur route in 16 hours 10 minutes, cutting the record by 23 hours. They later climbed the 3,000-foot formation seven times in seven days. Where most parties ascend Yosemite’s Leaning Tower in two days, he’s climbed it in two and a half hours. He’s taken expeditions to the Northwest Territories, Patagonia, Baffin Island, Colombia, Africa and Mexico. To date, he’s climbed El Cap 49 times via 29 routes. For these and other significant ascents, in 2016 Allfrey won the American Alpine Club’s Robert Bates Award for “outstanding accomplishment by a young climber.” The award is one of his most prized possessions.

Today he lives with his girlfriend of 10 years, Carmen Johnson, a speech pathologist, in Vegas. He ekes out a living as a climbing guide in Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, washing windows and collects a check from title sponsor The North Face.

“I’m glad to finally have a rest day,” he said over the phone, having recently returned from back-to-back climbing trips. But he soon admitted that a rest day doesn’t mean he’ll hit the couch and watch T.V. “I may end up doing manual labor in the backyard, which isn’t really a rest day activity, it’s windy out here like 50 mph gusts.”

Allfrey tending the anchor while partner Cheyne Lempe follows in Baffin Island (Cheyne Lempe).

Leading Zodiac’s Nipple Pitch while climbing El Cap with Alex Honnold (Gabriel Mange).

As we went to press, we learned that Allfrey and Carmen Johnson were married. Follow his travels on his website, davidallfrey.com, and on Instagram @daveallfrey.