- Yosemite E-Biking - 01/12/2023

- The Yosemite Climbing Association - 09/01/2022

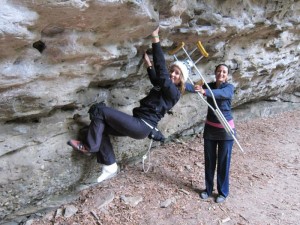

- Ryan Sheridan & Priscilla Mewborne - 05/17/2022

The limits of human endurance

By Chris Van Leuven

Chantel Astorga at 18,200’ on Denali’s (20,310’) Cassin Ridge after completing the Denali Diamond (Jewell Lund).

Two-thousand-five-hundred feet up El Capitan, a lone figure moves slowly up the wall, her headlamp flashing up and down as she looks for the next hand and foothold. It’s 2 a.m. on October 24, 2014.

As carabiners and assorted hardware clank against the cliff, she stumbles onto a ledge where two people are sleeping. She’s been out of water for eight hours, and in front of her are several two-liter bottles clipped to the anchor near the team. She knows she could rouse them and ask, politely, for something to drink that would keep her going. But that’s not Chantel’s style. She pulls her gear carefully around them, takes a final look at the water, and climbs on.

“At this point I was really hurting,” Chantel Astorga says from her home in Lowman, Idaho. “I wasn’t hallucinating but my reaction times were slowing down. I wasn’t truly in a state of crisis, I would’ve considered asking if that was the case. I didn’t think it would be fair to ask them and put them into a potential situation where they could run out of water.”

Meeting the Giri Giri Boys on Denali’s West Buttress

Chantel recalls the time in 2010 when she was guiding on the West Buttress of Denali and three Japanese climbers descended to the 14,000-foot camp having just completed one of the peak’s most difficult routes, the Denali Diamond. She could see in their eyes that they had been through a serious ordeal. They’d spent days high on the 20,320-foot peak, which feels higher – more like a 26,000-foot peak – due to its proximity to the Arctic Circle. This team, known as the Giri Giri Boys, are recognized as Japan’s top alpinists.

Soon after the Giri Giri Boys set up their tent, Chantel and her partner Kevin Hogan noticed silence instead of the familiar hiss of a stove inside of their neighbor’s shelter and concluded that the team was likely out of fuel and therefore unable to melt snow for water. For the next few hours the Giri Giri Boys slept. Then the men, Kazuaki Amano, Ryo Masumoto and Takaai Nagato, packed up their tent and continued down the mountain.

“Their style, approach, and aesthetics had a huge impact on me,” Chantel recalls. “They were samurais.”

What she saw from the Giri Giri Boys that day high on North America’s highest peak influenced her in two ways. One: if she gets herself into something, then she’ll see her way out of it. And two: she wants to climb the Denali Diamond, a route known for its beauty, clean granite and high commitment level. Four years later, after climbing two routes on Mt. Huntington with Salt Lake City based alpinist Jewell Lund, they agreed to do the route.

In June 2015, the two women spent four and a half days climbing with light packs and meager rations to overcome the Denali Diamond’s endless steep snow slopes and technically demanding terrain. After days of climbing in sync, and stepping up for one another when they sensed fatigue, they reached the intersection where their route met the Cassin Ridge. At this point they were at 18,200 feet and had been out of food for 24 hours. Chantel saw a red cloth sticking out of a crust of snow. “I started hacking it out with one of my tools and discovered the bag contained an old chunk of freeze-dried food. It looked like cardboard,” she says, laughing. “And we couldn’t have been happier.”

The women put down their packs, brewed up and eked out a pasta meal from the mystery chunk. With their spirits lifted and calories up, they continued to the summit. It was the route’s seventh ascent and first female ascent.

Choss and 30 Miles of Bushwhacking on Howse Peak

Though Jewell and Chantel have great success in the mountains, they often take longer to climb big routes than they plan for resulting in them running out of food.

She thinks back to 2014, to the scene of perhaps their greatest alpine challenge: Howse Peak in the Canadian Rockies. Before that climb, they hadn’t comprehended the scale of the remoteness and poor rock quality up north. “We were naive to the scale of the area,” Chantel says. The peak’s Northeast Buttress spanned for 5,000 vertical feet and required them to apply all their combined skills to make it up the route. “It required more physical and mental focus than any peak we’d climbed up to that point. That route is notorious for containing some of the worst rock in the range.”

Even the easiest pitches “… were fucked up and littered with such poor rock I was concerned that I’d kill my friend.” Tiptoeing through the loose terrain caused the team to take longer than they’d planned. They packed supplies for two days and ended up taking four. This included a torturous 30-mile bushwhack during the hike out. Word spread when they were overdue that they could be in trouble, but those who knew the team had faith that they were okay, and before a rescue was mounted, Jewell and Chantel made it back to civilization.

Linking El Cap and Half Dome in a Day

On September 22, 2012, I’m on assignment for Adidas Outdoor documenting Chantel and Mayan Smith-Gobat as they attempt to climb both El Cap and Half Dome in fewer than 24 hours, a feat yet to be accomplished by an all female team. It’s around 10pm and I’m huddled below a small boulder on the top of Half Dome trying to keep warm next to photographer John Dickey. I’m wearing Chantel’s small down jacket that comes down to my mid section. I’m shivering but the cold is the least of my worries: Chantel and Mayan have been on the go since about 2am and by our count, they’re past due.

Within the hour we hear the familiar jangling of gear smacking against stone and the faint sound of them from below: “Off belay!”

As the two mantel their way onto Half Dome’s summit, I can see under their dim headlamps the sign of deep mental and physical fatigue. Mayan sits down, puts her head between her knees, and cries. “I held it together until the end,” she says. A few moments later they hug, John snaps a few pics, and we descend together.

During the descent Chantel tells me that to prepare for the linkup she’d been training by mountain biking and lifting heavy weights in her garage. “I hadn’t been rock climbing that much,” she says. “I was psyched that I was able to pull that off.”

And pull it off they did, putting them into the history books of Yosemite climbing.

Taking a Break from Hard Climbing

After the linkup, Chantel quit climbing for a year and a half and raced mountain bikes instead. “I was in a period where I was uncertain of my life in climbing. So I decided to set it aside and focus on something else which was mountain bike racing.” She adds, “Although I did succeed with racing and enjoyed it, it also made me realize how much I do enjoy climbing and being in the mountains.”

Back in the Alpine

In early 2014 Jewell and Chantel reconnected and headed to the Alaska Range to climb Mt. Huntington. This was followed by Howse Peak and then Chantel soloed The Nose on El Cap with the intent to complete the route in a day. After dropping a few pieces of key gear (a jumar and an aider) and passing eighteen people, she fell shy of the 24-hour mark. A few weeks later, she attempted it again only to end up climbing on a windless day, running out of water and tapping deep into her reserves to safely make it to the top. “When soloing you need so much more water than when climbing with a partner,” she says.

After her final attempt on The Nose solo that season, Chantel knew she’d exhausted her mental reserves and put her goal on hold. Six months later, Jewell and Chantel climbed the Denali Diamond and once again Chantel’s reserves were depleted. “It takes weeks or months to recover when that happens.”

That autumn Yosemite climbing guide Miranda Oakley attempted to be the first woman to solo The Nose in a day but like Chantel, she took too long. Chantel knew Miranda’s reputation as a hard climber and knew she had a good chance of pulling it off. On August 5, 2016, Miranda climbed the route in 21:50. (Josie McKee soloed the route in sub-24 in November 2016, marking the second time the route was soloed in a day by a woman.)

I call Chantel about a week after hearing the news, and though she was impressed with Miranda’s successful ascent, I can tell by the tone of her voice that she’s a little bummed. However Chantel makes it obvious that her quest to solo The Nose in a day is also personal. After so many years of monumental effort and knowing what it would take to complete the challenge, the setback is more of a bump in the road than the end of a dream.

“I’ve been fortunate to succeed on many of the goals on the first go around,” she says. “But with The Nose, it didn’t play out that way and it’s something I’ve had to work harder for. I had the goal of wanting to be the first woman to solo it in a day, but later I had other goals that I put ahead of it. And I didn’t have it in me last year after the Denali Diamond.”

Chantel talks about her plans to return to Yosemite for a month in the fall. She also reflects on her past successes with Jewell, noting that the previous season the two didn’t complete the goals they set out to accomplish but she’s okay with that. “You’re not always going to succeed and there is perhaps more to learn from the trips where the summit is not reached,” she says.

If you’d like to learn more about Chantel, don’t look to Facebook or Instagram, as she prefers connecting with people in person. But hopefully you’ll have the chance to do just that, because she’s a fascinating woman with some incredible experiences to share.

Chantel sorts gear after soloing The Nose on El Capitan, Yosemite National Park (Madaleine Sorkin).

Chantel ascends the NE Buttress of Howse Peak (10,810’) in the Canadian Rockies (Jewell Lund.)

Chantel climbs solo toward El Cap Tower on The Nose route (Tom Evans).

Chris Van Leuven is the former digital editor at Alpinist Magazine. His story “Going Home,” on the cover of Alpinist 51, was recognized for literary excellence and is included in Best American Sports Writing 2016.