- California Enduro Series Announces 2024 Schedule - 11/19/2023

- ASHLAND MOUNTAIN CHALLENGE 2023 – CES RACE REPORT - 10/04/2023

- China Peak Enduro 2023 – CES Race Report - 09/04/2023

The man behind the legend

By Doug Robinson

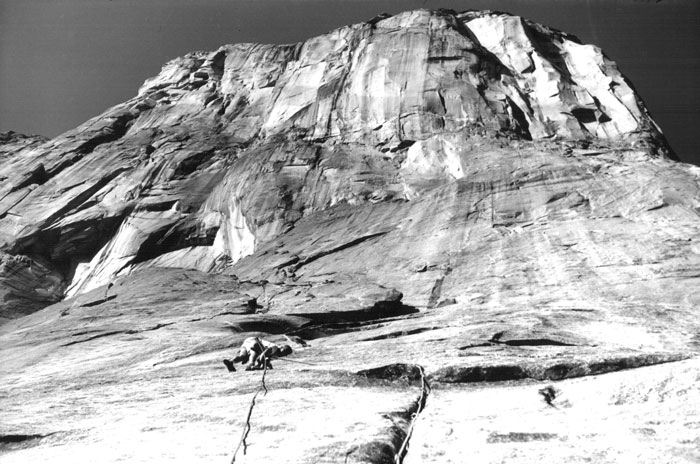

Royal and Liz Robbins atop El Capitan after Royal’s historic first solo ascent of El Cap’s Muir Wall in 1968 (Glen Denny).

A black Land Rover seemed to glide up the dirt road. We were pulling ropes out of cars and packing lunches; in the mid-1990s my climbing students were jazzed to be at Wamello Dome, a little-known destination of superb granite up an obscure logging road halfway between Yosemite and Fresno. Sleek with smoked glass widows, the Land Rover oozed a kind of captain-of-industry presence. Even under a patina of dust it seemed out of place here, where you’d more expect good ol’ boys in beatup bro trucks.

It came to a stop by me. The window whirred down and there was Royal Robbins, smiling cordially. It had been a few years, but this was the perfect place for a reunion; Royal had introduced me to this secret spot twenty-five years before, when I was guiding for his climbing school, Rockcraft. I loved the climbing and had been coming back ever since. This class from Foothill College was just the latest in a long line of appreciative students I’d brought here.

It turned out that Royal was on the same mission. The back of the Land Rover was teeming with Boy Scouts from the flatlands of his hometown, Modesto, eager for their first taste of adventure in the Sierra. What they didn’t know was that Royal was giving back. He credits the Boy Scouts with not only introducing him to climbing as a teenager in LA, but for fully turning his life around.

Royal Robbins is widely known as the kingpin of Yosemite’s golden age of big wall climbing, starting with leading the first ascent of the face of Half Dome in 1957. But few know that his childhood during the depression in West Virginia set him off on a rocky start. Royal’s mother was stalwart from the beginning, but his father – who Royal only really knew through scraps of legend about hunting bears in Alaska and surviving being marooned by a shipwreck there – disappeared early. He was followed by a stepfather, who insisted that the hapless lad take on his name. A drunk who was forever being fired from jobs, his lot improved, for awhile, with a move to Los Angeles, where WWII increased demand for machinists. But Royal’s mother’s hopes for a father figure for her young son were dashed as he beat the boy and then turned his fury onto her. Royal recalls his reaction as bewilderment, edging into self-blame. His ultimate response, though, was tellingly high-minded. “All I got from my two fathers,” Royal wrote, “were examples of boorish behavior and self-absorption.”

Anyone who’s interested will find that Royal has painted these scenes of his childhood quite unflinchingly in his recent three-volume autobiography, My Life. Climbing writer John Long said of volume one, To Be Brave, “If there’s a finer memoir, written by an American climber, I haven’t seen it.”

I agree (though I also love the snatches of autobiography, like small gems, in the writings of John Gill). I lived shoulder-to-shoulder with Royal in Camp 4 during the magical sixties. We all did, without knowing – really – where each other came from. And why. Instead, our day-to-day lives were more riveted in the eternal present, absorbed in striving against the exacting demands of the Valley’s slippery granite. Who each of us were tended to be judged more by our most recent climb rather than the pasts we had left behind. Only later could we relate our backgrounds to our strivings, and it took Royal – among many other climbers – decades to bring those links forth into print. It’s been well worth the wait.

By the time his stepfather’s life flamed out, Royal was ranging more widely in search of adventure, body surfing Santa Monica, hitchhiking everywhere, and riding the rails hundreds of miles across Southern California. Intriguingly, like Dean Potter generations later, Royal had recurring dreams of flying. “My dream-flying, however,” he wrote, “could occur only by dint of great effort. I flew because I would … I didn’t understand yet that perseverance is a gift too.”

As a preteen afloat in Los Angeles, Royal had begun flirting with the life of a street punk, ganging up for a string of petty burglaries – “money was a secondary goal … our burglaries were more about adventure” – that led to a stint of several days in juvenile hall. Then a Boy Scout leader took him climbing, and Royal’s life abruptly changed. “Scouting was a lifesaver that kept me from drowning in a sea of anarchy and aimlessness.” His first climb was Fin Dome, just off the John Muir Trail. He loved it, and was hooked: “I had learned there was a power within me that I hadn’t dreamt existed, a power to climb.” Interesting to me, because it showed how events are all about perspective. I had grown up camping in Yosemite, sailing over its granite swales, so when I passed by Fin Dome at about Royal’s age on a backpacking trip with my Dad – who had introduced me to the Sierra and been a wonderful presence in my early life – the climb that had so inspired Royal hardly seemed worth scrambling up.

Soon Royal found Stony Point, a collection of sandstone boulders and minor cliffs in Chatsworth, out on the edge of the San Fernando Valley. He could hitchhike there after school, and in old snapshots we catch glimpses of a gleeful teenager in Converse tennis shoes who is tearing up the place. A good sixties film, one that features Royal and Yvon Chouinard climbing the West Face of Yosemite’s Sentinel Rock, actually opens with scenes of Stony Point, showing it as a cradle of modern California climbing. There, Royal quickly met all of the era’s most active climbers (with the interesting exception of John Salathé , who was beginning a decade as Yosemite’s most innovative climber – though hardly anyone else in California had even heard his name yet). Royal was swept into the folds of Sierra Club climbers, where his talent immediately stood out, along with a brashness they took as arrogant, even though he was barely in high school. The rest soon became history.

Royal’s climbs simply dominated Yosemite’s golden age of big walls in the 1960s. Many have praised his style, but maybe a totally contemporary view says it best. We were all struck by Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson’s brilliant free ascent of El Capitan’s Dawn Wall last January. Here’s how Tommy summed up Royal’s influence: “Royal Robbins is one of my greatest heroes. He has been acknowledged as a bold visionary, the man who started a ripple in the culture and ethic of climbing, who has directed and inspired every climber since, whether they know it or not.”

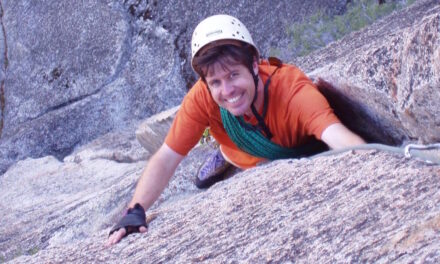

Less well-known, but a telling aspect of his character, was Royal’s influence beyond the elite, on generations of rank-and-file climbers as a guide and climbing instructor. His climbing school, Rockcraft, began at Lover’s Leap late in the 1960s, the second (or possibly third) climbing school in California. He would write two modest-looking little books, Basic Rockcraft and Advanced Rockcraft, which were hilariously illustrated by Yosemite’s bon-vivant cartoonist Sheridan Anderson. They seemed extremely modest when compared with the eye-catching photos of alpine instruction (not to mention the elegant sweaters) in Gaston Rebuffat’s On Ice and Rock, yet their influence was huge. Hear it from Ron Kauk, whose free climbing dominated Yosemite in the 1980s and beyond: “As a fourteen-year-old I used to hide out in the back of the classroom and study something from another world. My textbook was Basic Rockcraft by Royal Robbins … I find in Royal’s writing a kind of love story that ultimately touches my own heart through his commitment to adventure, as well as his honesty.”

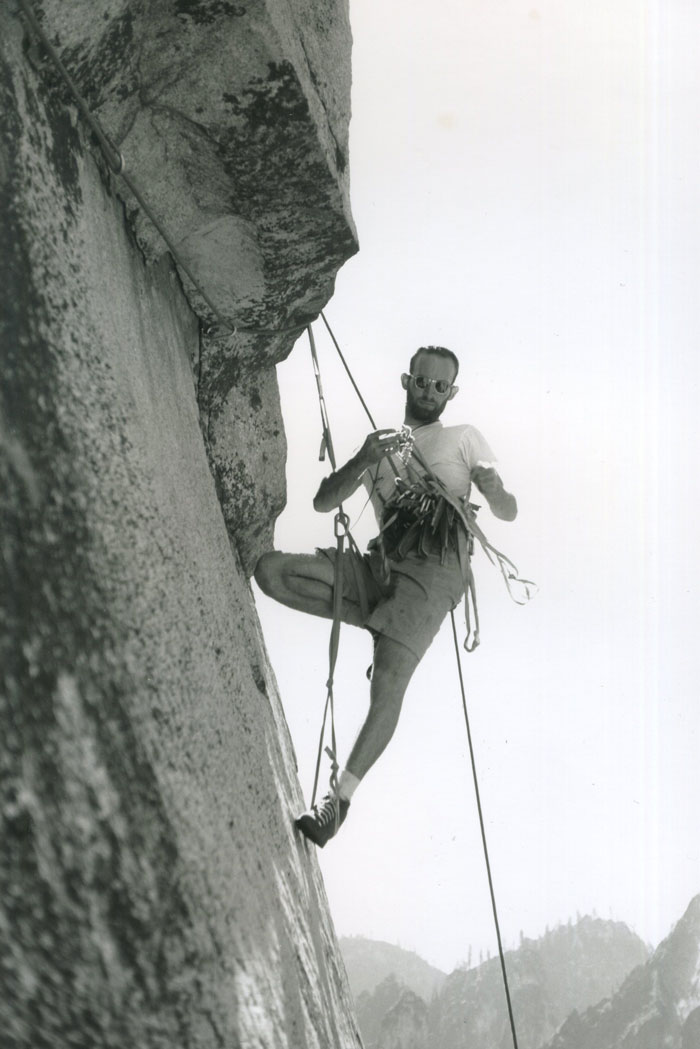

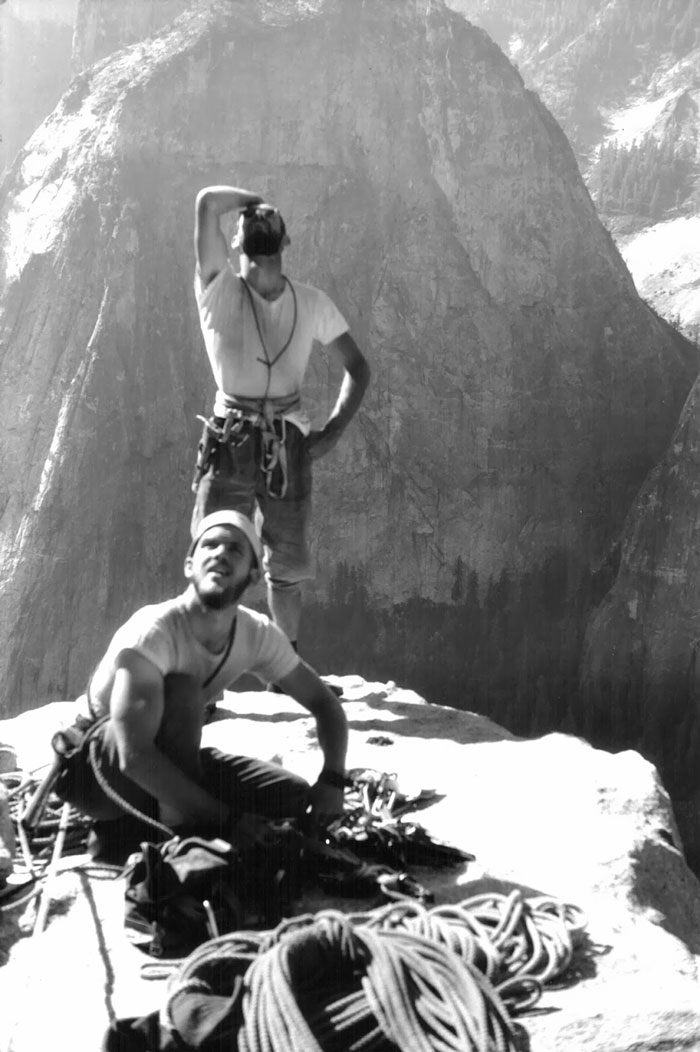

TM Herbert and Royal organizing gear in Camp 4 during the golden age of big wall climbing (Tom Frost).

Yes, Royal inspired generations of climbers. I got to witness it up close through the early 1970s, when I worked for him as an instructor and guide. Royal had just moved his Rockcraft climbing school to the region around Wamello Dome, which was then unknown to climbing. He christened it The Hinterlands. Every week a caravan of students and instructors would follow Royal’s red and white VW bus up those dusty logging roads. We went to the Balls, we went to Shuteye Ridge, always exploring. The adventure was palpable. Royal didn’t mention it, he lived it, and brought us along. I would lead students up a barely-mapped-out route, while Royal soloed to check out what would become the next day’s climbs.

His footwear was a curious anomaly. Recently on the market was a climbing boot Royal had designed. It featured a stiff lug sole, and of course royal-blue suede. Friction was not the strong point of “RRs,” so Royal usually wore soft, gummy Tretorn tennis shoes to solo on the slabby domes. That intrigued me enough to go buy a pair too.

I vividly recall the first day Royal took us to Wamello Dome. It’s Fresno Dome on the maps, but Royal had read of John Muir going there, and Muir mentioned that the local Indians called it Wamello. We hiked up from below. Stately pines gave way to a major dome bristling with climber-friendly features. Immediately I grabbed a couple of students and started up the South Buttress, its longest route. Soon I was slinging runners around gargoyle-sized plates to protect climbing that romped upward. It may even have been the first ascent, though no one seemed to care; the Hinterlands bristled with granite domes and now has several guidebooks.

I last saw Royal two years ago. His sixties wall-climbing partner Tom Frost had organized the Oakdale Climber’s Festival. Pushing eighty, Royal’s arthritis (which he playfully named “Arthur”) seemed to be getting the best of him, and he accepted a hand to join Frost onstage. The crowd hushed to hear two of the golden age’s “fab four” (Pratt was dead, and Chouinard not in attendance) talk about their legendary adventures together. Fielding questions from the audience, they joked with us and with each other. Their relaxed wit sparkled, and often a paragraph-long question would evoke a two-word answer. The perfect two words.

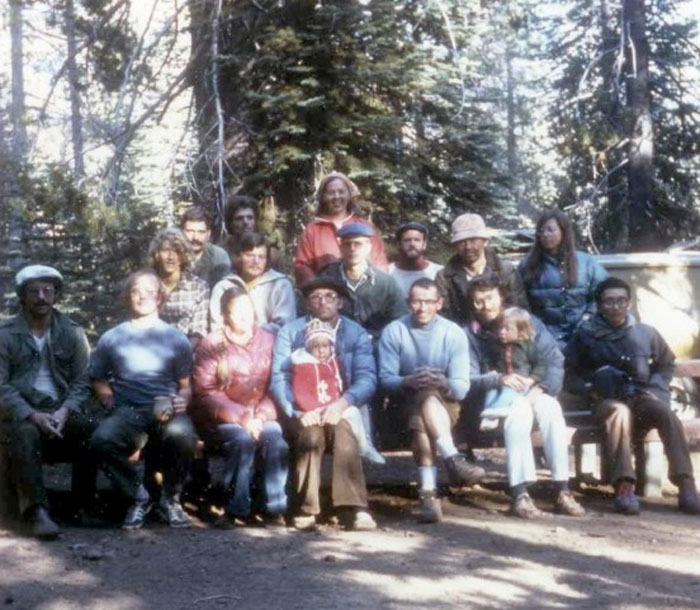

A Rockcraft climbing camp gathers around Royal, in the middle with his young daughter Tamara on his lap, in the 1970s (SuperTopo/Roger Breedlove).

Royal climbs the third pitch of the Salathé Wall on El Capitan during the first ascent by Robbins, Pratt and Frost in 1961 (Tom Frost).

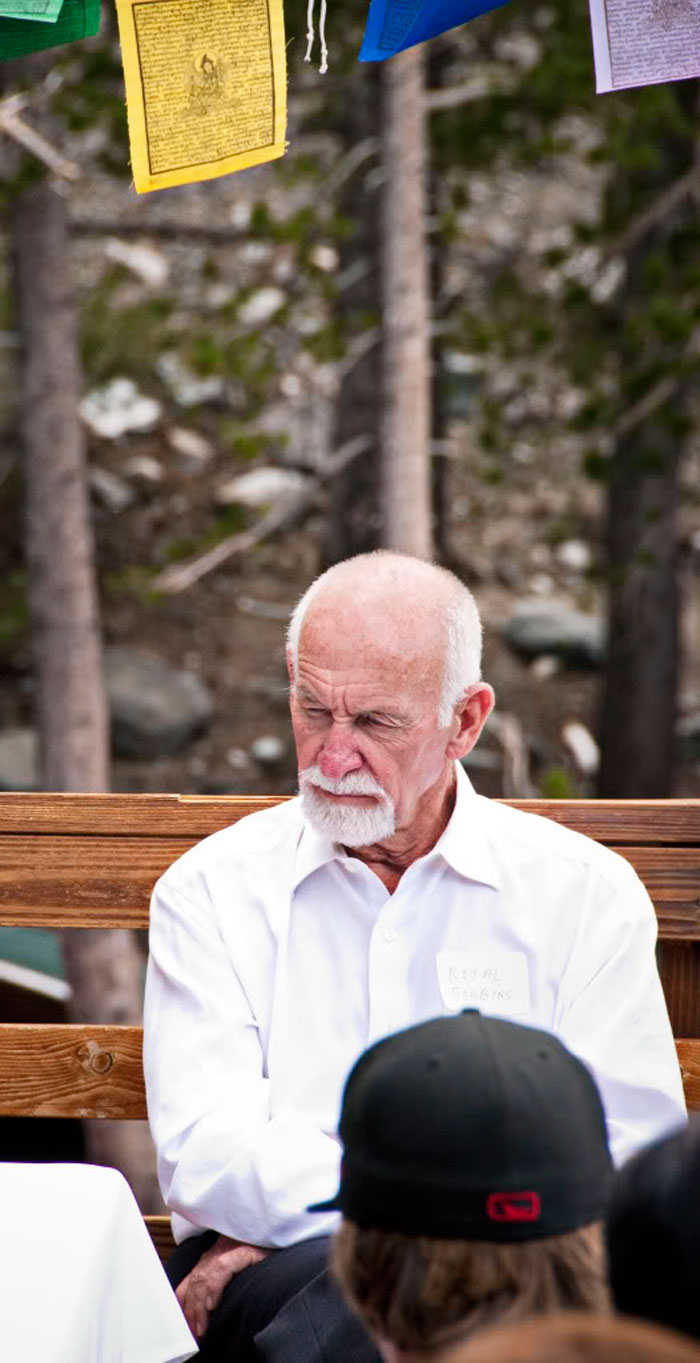

Royal is pensive at the memorial for John Bachar, Yosemite’s greatest soloist prior to Alex Honnold bursting onto the scene (Peter Haan).

Chuck Pratt and Royal Robbins atop El Cap Spire during the first ascent of the Salathé in 1961 (Tom Frost).

Doug Robinson has moved back to the Sierra, where he climbs and skis pretty hard for a guy collecting Social Security, and tours to promote his recent book, The Alchemy of Action, which Doug claims finally answers the riddle of why people climb. Recently he has joined with Flatlander Films to work on a major biopic about his old friend Tom Frost.

Doug Robinson has moved back to the Sierra, where he climbs and skis pretty hard for a guy collecting Social Security, and tours to promote his recent book, The Alchemy of Action, which Doug claims finally answers the riddle of why people climb. Recently he has joined with Flatlander Films to work on a major biopic about his old friend Tom Frost.