- Death Valley’s Battle With Climate Extremes - 01/01/2024

- The Future of Homewood - 12/05/2023

- Kula Cloth - 10/18/2023

How Beth Pratt is saving cougars with wildlife crossings

The jury is still out on the chicken, but we know why the mountain lion crossed the road. Or at least why one particular mountain lion crossed two busy highways. He was looking for a date. He found a home.

Ten years ago, a lone male mountain lion made international headlines when he settled down in Griffith Park, eight square miles of open space in Hollywood, surrounded by urban development. Scientists named him P-22. His story, along with the tireless efforts of Beth Pratt, Regional Executive Director of the National Wildlife Federation, helped raise over $76 million for an enormous wildlife bridge across Highway 101.

Liberty Canyon, at the Ventura Freeway, is the last 1,600 feet with undeveloped land on both sides of Highway 101 in the Santa Monica Mountains. It separates the Santa Monica Mountains from the Simi Hills and beyond, creating genetic isolation for animals large and small. Even with vast open spaces, the area mountain lions face extinction from inbreeding due to lack of dating options. Mountain lions face a similar dilemma in the Santa Cruz Mountains, and several wildlife crossings have been proposed for Highway 17.

P-22, when he was recaptured in April 2019 to replace the battery in his GPS collar. Photo: National Park Service.

But the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, named after the philanthrophist who donated $25 million, is past the proposal stage of development. Construction will begin by spring of 2022. The crossing won’t help P-22 find a mate — Griffith Park is about 30 miles east of the proposed bridge across Liberty Canyon. But its strategic location, surrounded by open space and spanning ten lanes of pavement will prevent the extinction spiral of isolated populations. “This wildlife crossing will allow animals to date outside of their family!” Pratt explains.

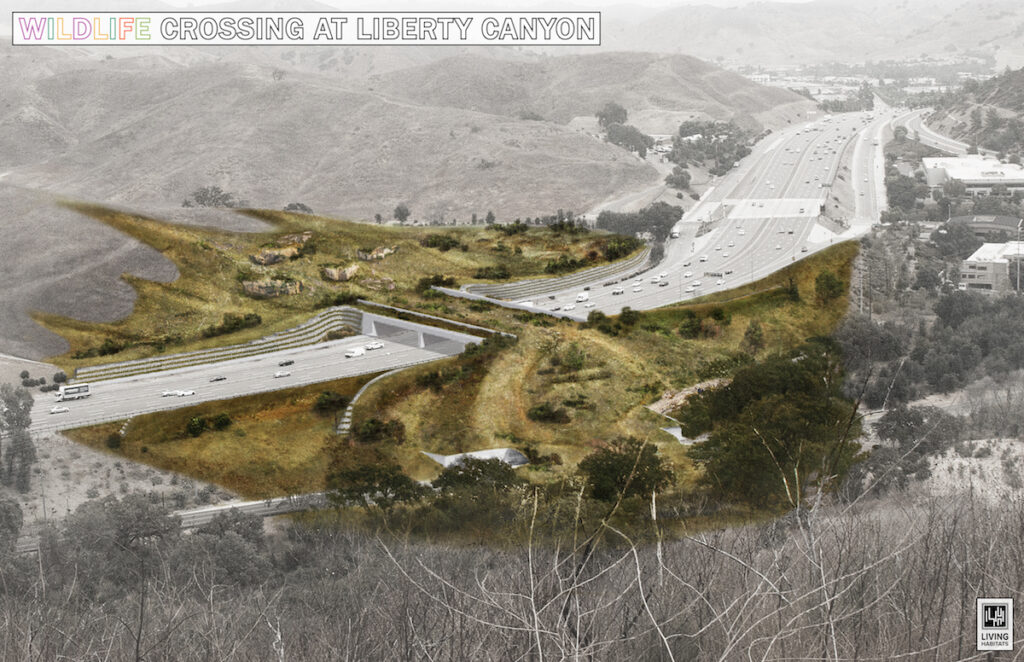

Wildlife crossings like this one look like a slice of the local ecosystem suspended on a concrete platform above traffic; a bridge for flora and fauna. Engineers consider light and noise, trees and shrubbery when designing these structures that will support the weight of a natural landscape.

Pratt began working on the estimated $87 million Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing in 2012, the same year P-22 arrived in the LA area. She gets calls to advise on other projects but devotes most of her energy to the nation’s largest urban wildlife crossing in the nation’s second largest city. She’s given Governor Newsom a tour. Celebrities like Leonardo DiCaprio, David Crosby and Barbra Streisand have contributed to the cause. Donations roll in from across the country and around the world.

Visualization of the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing by Living Habitats, LLC Courtesy of National Wildlife Federation.

Meanwhile P-22 has settled into an urban bachelor existence. The chances of a female mountain lion crossing one of the major highways that ring his new home are slim. Most towns would have a problem with a 140-pound predator prowling in backyards, but LA embraces him.

“P-22 is in a park that 10 million people visit every year!” enthuses Pratt. “In any other state in the country he would have been shot or relocated right away. But in LA, people celebrate him, they report sightings of him wandering around at 2 AM like any other celebrity. He’s a folk hero. LA is coexisting with mountain lions.”

P-22 has a Facebook page with over 16,000 followers. Pratt even made him a fake Tinder profile. “We do a lot of education and outreach work in Watts,” explains Pratt. “Folks there see P-22 as a symbol of systematic oppression, they notice that he struggles with a lot of the same things they do.“ This dateless mountain lion’s story has captured imaginations around the world and changed the way people think about the wild.

“Thirty years ago, the dominant view was to put wildlife in a refuge and put people in a place like LA, and check the box, we saved wildlife,” says Pratt. “Now we understand that even having a place like Yosemite isn’t enough. Of course we need to keep putting aside places for wildlife, but they also need connectivity.“ All animals, from the tiniest pollinators to the most charismatic mammals, need to move so they can find mates and new territory.

At the Los Angeles Zoo, introducing P-22 to Sean Penn and Leila George. Photo from Pratt’s private collection.

Wildlife crossings are not a new idea; France began building them in the 1950s. Canada built a single dramatic overpass in the heart of Banff National Park 25 years ago; now there are 42 wildlife crossings along an 88-km stretch of road. The idea is gaining traction; in November 2021, Congress allocated $350 million for wildlife crossings throughout all 50 states.

“Where humans see a highway, animals see a wall,” explains Pratt. Building wildlife crossings, either bridges or tunnels, opens up new terrain. Elk, deer, bears, coyotes, toads and even plants benefit. Vehicle collision numbers fall.

“What’s even more alarming than one species going extinct is that the research by the National Park Service is starting to show that genetic isolation is impacting all species. The timeframe is not as imminent for lizards and birds, but they still face threats,” Pratt sighs. “Turns out that when you plop down a 10-lane freeway in the middle of an ecosystem, that has consequences.”

And those consequences ripple out to the human world in complex ways. The extinction of the Eastern panther led to a dramatic rise in their main prey, deer, which may have resulted in a spike in Lyme disease. “And the pandemic! Why are we having a pandemic?” Pratt asks rhetorically. “It’s because of habitat degradation and loss.“

“We are in the middle of the sixth mass extinction, and unlike the previous five, we are the cause, we are the asteroid,” Pratt says. “The moral responsibility to the rest of life on earth is huge. But we also need to shape up for our own survival.”

Decades of science demonstrate that wildlife will find and use these crossings. “They don’t want to cross the road. Animals are looking for every option to avoid crossing a busy highway,” says Pratt. “I visited a crossing in Colorado, deer started using it two days after it was done. And some deer tried to use a crossing on the I-90 Snoqualmie Pass before it was even finished.”

Beth Pratt, wearing a P-22 themed holiday sweater, at the site of the soon-to-be wildlife crossing. Photo: Beth Pratt’s Private collection

In a culture and a time that is saturated with bad news, it’s encouraging to realize that some problems have practical solutions. “When you look at climate change, it’s overwhelming, there is no magic bullet. But wildlife crossings are a magic bullet. Wildlife are getting hit by cars, you build a crossing, the problem is fixed.”

Solutions happen in our own backyards. Pratt is currently fighting a proposed 60-mile graded trail along the Merced River near her home. “I’m all for recreation, and ten years ago I wouldn’t have thought anything of it,” she explains. “But an improved and graded trail along a riparian ecosystem disrupts how animals move and use the landscape. It could make newts and butterflies go locally extinct.”

Each of us can help wildlife survive by changing the way we view new construction, and advocating for building that allows wild animals to thrive. “Our human infrastructure impacts wildlife in ways we didn’t expect,” explains Pratt. “We need to see the land and human development in a whole new way.”

Read more articles by Leonie Sherman here.