- Death Valley’s Battle With Climate Extremes - 01/01/2024

- The Future of Homewood - 12/05/2023

- Kula Cloth - 10/18/2023

Appreciating the timeless rhythm of the tides, sun and wind in the Channel Islands

By Leonie Sherman

Slack-lining and ukulele in a wind shelter at Water Canyon campground (Joanne Schwartz).

THE ENGINE GROANED AND THICK CURTAINS OF WHITE FOAM parted in twin waves as our boat picked up speed leaving Ventura Harbor. Within ten minutes, the water’s surface a hundred yards from the bow boiled with sleek grey bodies. Over 150 dolphins sped towards the boat, a wall of marine muscle. As they got closer they fanned out and began to play in our wake, dashing under the bow to emerge on the other side, dancing in the froth and surfing the waves we left behind. Passengers on the Island Packers ferry to Channel Islands National Park, 20 miles from the mainland, aren’t always greeted by an exuberant welcome committee demonstrating how to enjoy life. But after a few days on these enchanted isles, most visitors can figure it out for themselves.

Channels Islands National Park, established in 1980, preserves five diverse islands and their ocean surroundings. Barren Anacapa Island, closest to shore, has a lighthouse dating from 1932. Santa Cruz Island, the largest, features sea caves and thousands of rare foxes. Santa Rosa is ringed by miles of deserted white sand beaches and hosts a stand of Torrey Pine, one of the rarest trees in the world. Windswept San Miguel has a seal rookery thousands strong. The southernmost island, Santa Barbara, draws nesting seabirds. None of the islands were ever part of the mainland, but during the last Ice Age they were less than five miles from shore. Mammals and seeds rafted over on debris and evolved in isolation. Over 150 species of plants and animals are endemic, found nowhere else on the planet. Temperatures remain mild throughout the year; early winter boasts vivid sunrises and sunsets.

Chumash natives lived on these islands 8,000 years before the pyramids were a glimmer in a pharaoh’s eye, 2,000 years before people settled in Jericho, the longest continually inhabited city on the planet. The Chumash were the finest boat builders in California and navigated the Santa Barbara Channel in tomols, plank canoes up to 30 feet long, capable of carrying ten passengers. The shell bead money they manufactured on Santa Cruz Island was traded extensively with mainland groups. Santa Rosa had at least eight villages, San Miguel had two, Anacapa was seasonally inhabited and Santa Cruz Island hosted eleven sites. Every village had a sweat lodge and a flat open area for dancing and ceremonies. The land and ocean provided a rich and varied diet.

225 years after Sebastian Rodriguez Cermeno traded some pieces of taffeta and cotton cloth for 18 fish and a seal, the last original inhabitants were forcibly removed to the mainland. Disease and violence decimated their way of life; by 1910 there were fewer than 100 Chumash left. Today over 4,000 people who identify as Chumash are revitalizing their culture, with presentations, storytelling, dances and basketry demonstrations. They’ve also brought back the tomol. In 1976, a group of Chumash built the first tomol in over a century and paddled from San Miguel to Santa Rosa and on to Santa Cruz Island. Twenty years later, the Chumash Maritime Association built the ‘Elye’wun — Chumash for swordfish — a 26-foot long tomol. In 2001 it made the historic journey from the mainland to Santa Cruz Island, where 150 Chumash waited to meet them. Three years later, the ‘Elye’wun completed the journey again. This time the paddlers were joined by a crew of young Chumash and welcomed by over 200 friends and family when they arrived at Swaxil, a historic Chumash village now known as Scorpion Valley. The 21-mile journey took ten hours.

The same crossing takes only an hour on the Island Packers Ferry. Most passengers get off at Scorpion Bay on Santa Cruz Island, to kayak around the roaring colorful basalt sea caves, hike the canyons, enjoy the charming visitor center or stay in the 31-site campground, half a mile from the pier. The Nature Conservancy owns three quarters of the island and only allows access with permission or a guide. The island is home to Santa Cruz Island Pygmy Foxes, who resemble their mainland relative the gray fox, but are the size of a housecat. Thirty years ago there were fewer than 200 left in the world. The National Park Service and Nature Conservancy cooperated in aggressive restoration efforts and today over 2,000 tiny foxes roam the island. They lurk around the campground hoping for an easy meal from a careless camper.

Sunrise from the ridge above Scorpion Bay (Leonie Sherman).

My friend Joe and I were heading to Santa Rosa Island. An hour and a half after departing Scorpion Bay, the low rolling hills of the island came into view. In addition to all our camping gear and toys, our boat carried special cargo: two juvenile sea lions. Months ago they’d been found emaciated and injured on the mainland. The dedicated staff and volunteers of the Channel Islands Marine and Wildlife Institution nursed them back to health and planned to release them near a popular sea lion hangout. In a rocky cove just offshore a raft of four dozen sea lions pranced and dove like synchronized swimmers. The boat slowed and the juveniles’ cages were hung off the side and tipped towards the ocean. One of them slipped below the surface and then flung his body out of the water, literally leaping for joy before racing off to join his brethren.

At Beecher’s Bay, a long wooden pier led towards a ranching complex, active from the turn of the century until 20 years ago. During their tenure, Vail and Vickers, the ranch owners, blasted roads through steep canyons, introduced elk and deer for sport hunting and leased land for oil exploration. The ranch house, bunkhouse, two barns, and schoolhouse now host interpretive displays, rangers and restrooms. A visitor’s first impression is of dusty corrals and rusted farm equipment.

But beyond the ranching complex, the scars of the island’s ranching past fade as campers cross a wide windswept marine terrace. Skunk Point, a white sand fringed spit of land, frames the vivid turquoise waters of a broad bay. Silhouettes of Torrey Pines bristle on a distant rolling ridge. The clamor of modern civilization is replaced by the pulsing roar of the ocean and the rustle of wind through dry grass. Idle chatter drops away and a visitor can’t help but stand in mute awe of this island paradise.

A mile and a half past the pier, the campground is tucked into steep-walled Water Canyon. A trickle gurgles along the canyon floor, creating a winding ribbon of vivid green that grows to a murky creek before it meets the ocean. Sturdy wooden wind structures and a picnic table mark each of the 15 camp-sites. We quickly befriended our neighbors; Steve had visited Santa Rosa over two dozen times and 70-year old Joanne used to lead kayaking trips around the island. Our days fell into the relaxed cadence of island life, paddling and kayaking, hiking and botanizing, slack-lining and doing yoga. Evenings were devoted to cooking Steve’s freshly caught fish and admiring the vivid splash of the Milky Way across the darkest sky. Five days passed in a dreamy trance, immersed in the timeless rhythm of tides and sun and wind. We returned to the mainland in love — with each other, with the islands, with the flavor of a wilder southern California.

Break and uke time on the hike from Prisoners Bay to Scorpion Bay, Santa Cruz Island (Leonie Sherman).

Rocky bays and inviting waters, Santa Rosa Island (Leonie Sherman).

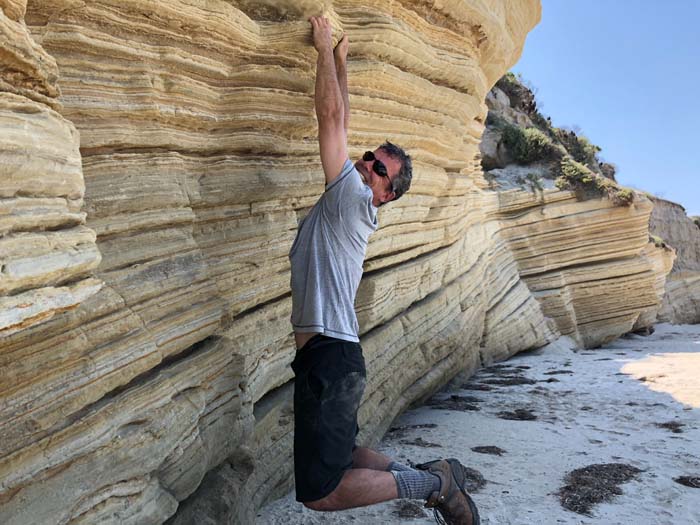

Joe McCullough climbing sandstone cliffs (Leonie Sherman).

Dinner time (Joe McCullough).