- Death Valley’s Battle With Climate Extremes - 01/01/2024

- The Future of Homewood - 12/05/2023

- Kula Cloth - 10/18/2023

After nearly forty years Save Our Shores continues its heroic work

By Leonie Sherman

Passionfish restaurant volunteers care for Lover’s Point in Monterey as part of SOS’s Adopt A Beach program.

Lots of people move to Santa Cruz to be near the ocean, but Rachel Kippen moved there to save it. After years of working on marine science and policy from Orange County to San Francisco Bay, she got frustrated talking about problems but not participating in solutions. “I wanted to be part of a group that did advocacy and education and accomplished measurable goals,” she explains. “Save Our Shores was the only logical choice.”

Without the work of hundreds of Save Our Shores volunteers and dedicated staff, the pristine coast that millions of us love would be marred by oil derricks. There would be a few more tons of plastic pollution off-shore, and tens of thousands of school kids might not understand how their actions on land affect the health of the oceans we rely on for food, recreation and the very air we breathe.

But those sweeping changes were hardly imaginable for the small group of volunteers who coalesced in 1976. The California Coastal Act, passed in 1972, empowered this collection of surfers, sailors and activists to understand the fate of the oceans as their personal responsibility. When industry began eyeing the Central Coast for off-shore oil drilling, the concerned citizens who would become Save Our Shores turned their attention and energy to legislation.

Though the Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors had opposed a permit for off- shore oil exploration in 1967, there was no policy governing drilling off the coast, or the on-shore facilities that accompany these rigs. Santa Barbara’s 1969 oil spill triggered environmental concerns. The group of folks who incorporated as Save Our Shores in 1977 reasoned that decisions effecting local beaches should rest with local communities. Their hard work led to Ballot Measure A.

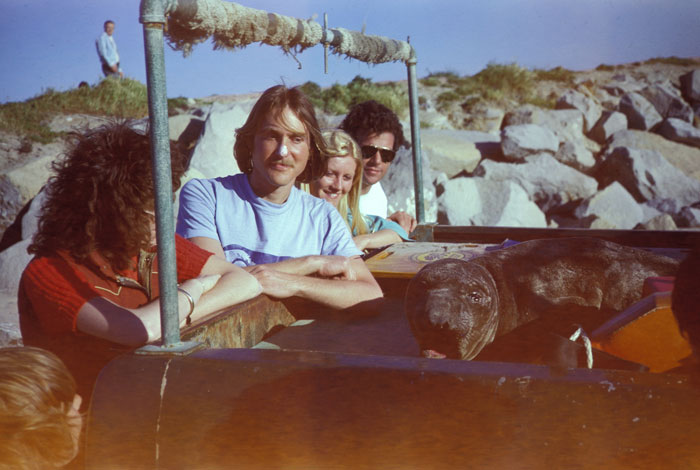

Dan Haifley (right) and Santa Cruz City Councilmember Don Lane (left) on

an oil platform off Vandenberg Air Force Base in the early 90s.

Approved by 85% of Santa Cruz voters in 1985, Measure A created a de facto moratorium on drilling off the coast of Santa Cruz by requiring a popular vote for the creation of on-shore facilities. The city of Santa Cruz went the extra mile and contracted with Save Our Shores to organize communities up and down the coast. Save Our Shores hired Dan Haifley as their first paid staff member and he travelled from San Diego to Crescent City, speaking with anyone who would listen about Measure A and local control of the marine commons. His energy and passion led to the passage of 26 other ordinances similar to Measure A.

This radical legislation was accompanied by a cultural sea change. These days a single oil platform off of Vandenberg Air Force Base in Santa Barbara County is the northernmost off-shore rig along California’s thousand plus miles of coast.

Not content to rest after such a monumental achievement, Save Our Shores then turned its attention to the other regulations proposed for the Monterey Bay Sanctuary, including water quality. They had their eye on nothing less than permanent federal protection of the Monterey Bay.

The creation of the country’s first National Marine Sanctuary off the coast of North Carolina in the early 1970s protected the sunken USS Monitor civil war ironclad. Save Our Shores aimed to protect mostly biotic, environmental and recreational resources under the same rubric. Super human commitment and dogged persistence led to unlikely alliances. In 1992, in an effort to woo moderate Republicans, George H.W. Bush designated the Monterey Bay Marine Sanctuary.

Spanning five counties and containing four harbors, the Monterey Bay Marine Sanctuary is the most heavily impacted of the nation’s fourteen Marine Sanctuaries. Save Our Shores Executive Director Vicki Nichols realized that community engagement was the key to protection. She started the Sanctuary Steward program, and created an army of uber volunteers who do community outreach to fishermen and boaters, make educational presentations and haul thousands of pounds of trash off the beaches every year.

The first Save Our Shores beach clean up took place in the early 1970s. Last year they organized over 350 beach, river mouth and neighborhood clean ups and removed over fifty thousand pounds of trash. Seven years ago, they began collecting data about the stuff they were picking up along the Monterey Bay Marine Sanctuary’s 276 miles of shoreline. The results were shocking; 78% of the trash they removed was plastic. Save Our Shores staff set out to reduce the amount of plastic that ends up in the ocean – globally there are over five trillion pieces of the stuff floating around – through a plastic bag ban.

“Banning single use plastics is a totally different ball game than banning off- shore oil drilling, but they’re both related to carbon use and ultimately climate change,” Rachel Kippen explains.

In 2007, San Francisco became the first city in the nation to ban single use plastic take-out bags. The plastic industry promptly sued them. Instead of scaring other cities into abandoning their own plastic bag bans, the lawsuit only encouraged collaboration as cities joined forces for regional environmental impact reports and legal support. By January 2014, a third of all Californians, about ten million people, lived in areas that had banned single use plastic take-out bags. A state wide plastic bag ban was signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown, but a bitter fight from the plastics industry means the issue will come before voters in the 2016 election.

Ultimately, though, reducing plastic pollution in the ocean is not just about legislation, it’s about changing behavior. Towards that end, Save Our Shores runs educational programs in local schools that help students understand the importance of their actions on the fate of the ocean in their backyard. They’ve reached tens of thousands of students in the city of Santa Cruz through in-school presentations and collaborations with O’Neill Sea Odyssey.

In October of 2014 they launched a program to reach under-served communities in Pajaro Valley, northern Monterey County and the Live Oak area. Ten months later, they’ve brought over two thousand kids – many of whom live within twenty miles of the ocean but have never visited a beach – out to experience the windswept shoreline of the Monterey Bay.

Contemplating the fate of our oceans can be a terrifying experience. Issues like climate change, biomass extraction and changing ocean chemistry are abstract and it’s hard to see how one person can make a difference.

Dan Haifley insists that change has to start with each of us and prescribes

a simple three step program that can drastically improve the health of our oceans if we all get on board. The first step is to be aware of what you eat, and only consume seafood approved by the Monterey Bay Aquarium on their wallet- sized Seafood Watch cards. The second is to dispose of waste properly, reusing, repurposing, recycling and composting whenever possible. The final step is to reduce your personal carbon footprint; the more carbon you burn, the more ends up in the ocean.

The actions of beachcombers, joggers, surfers, paddlers and kayakers influence popular opinion, which in turn affect political decisions. During the course of writing and researching this article, I’ve picked up dozens of cans and bottles from local beaches and changed the way I order drinks: I’ve started asking my server to leave out the straw, which is just another piece of single use plastic destined for the landfill at best, and the Pacific at worst. Are there any steps you can take to improve the health of our oceans today?

For more information, visit saveourshores.org.

About ASJ’s EPiC program | Doing great work in California? We want to help you reach your highest potential!

About ASJ’s EPiC program | Doing great work in California? We want to help you reach your highest potential!

The EPiC program is ASJ’s way to spotlight the exemplary work of some of California’s non-profits that are dedicated to promoting stewardship and access for the adventure sports community throughout California.

Our mission is to provide inspiring coverage of California’s epic terrain, and to help the outdoor sports community preserve and maintain access for future generations.

We encourage outdoor non-profit organizations based in California to contact us for the chance to be featured in our publication and receive FREE display and web advertising space.

For more information, email asjstaff@adventuresportsjournal.com.