- Death Valley’s Battle With Climate Extremes - 01/01/2024

- The Future of Homewood - 12/05/2023

- Kula Cloth - 10/18/2023

Saving open space for all of us

By Leonie Sherman

Rumor has it that the Truckee Donner Land Trust started around a kitchen table, but one founder, John Eaton insists it was a fireplace. Twenty-five years ago he was working on land issues with local environmental and political groups. He became convinced that a whole new kind of organization was necessary to save open space and preserve the rural character of his beloved home in the northern Sierra.

“You really can’t save open space through just litigation. And you can’t really save open space just through zoning,” he explains. “if you want to preserve open spaces, you absolutely have to have a land trust.”

“Of course, I knew nothing about land trusts when I had this realization,” he laughs. “But I talked to a friend who knew somebody who did, and they knew somebody who was interested, and pretty soon seven of us were sitting around my fireplace.”

They set their sights on 160 acres on Coldstream Canyon behind Donner Lake. With an all volunteer staff and very little experience, they managed to raise several hundred thousand dollars. As the number of volunteers grew, the group moved meetings to the infamous kitchen table and turned their attention to bigger projects. In 1996 they hired their first paid staff.

A quarter of a century later, the Truckee Donner Land Trust has preserved over 34,000 acres of stately forest, rolling meadows and historic landmarks. They have six full-time staff and additional seasonal summer employees. They’ve engaged hundreds of volunteers and partnered with dozens of local and national organizations. And they’ve raised millions of dollars to accomplish their goals.

In 2002, with the help of the Trust For Public Land, they tackled their first multi-million dollar project, raising over 2 million dollars to purchase an additional 2,200 acres backing onto Donner Lake. Five years later they raised 23.5 million dollars to save Waddle Ranch in Martes Valley near North Star. “That land had underlying entitlements for more than 1300 homes,” says Executive Director Perry Norris. “To pull all of that out of the equation was a tremendous victory.”

Norris was hired as Executive Director fifteen years ago and he brought significant changes. “Prior to that we weren’t super effective or organized,” admits Eaton. “They first brought Perry on as a fund raiser, which he’s very good at. If there’s land that needs to be protected he’s going to make it happen.” Eaton pauses. “Perry is also a very good negotiator. He’s brilliant at persuading people to sell us their land. His attitude has really carried us forward into the 21st century.”

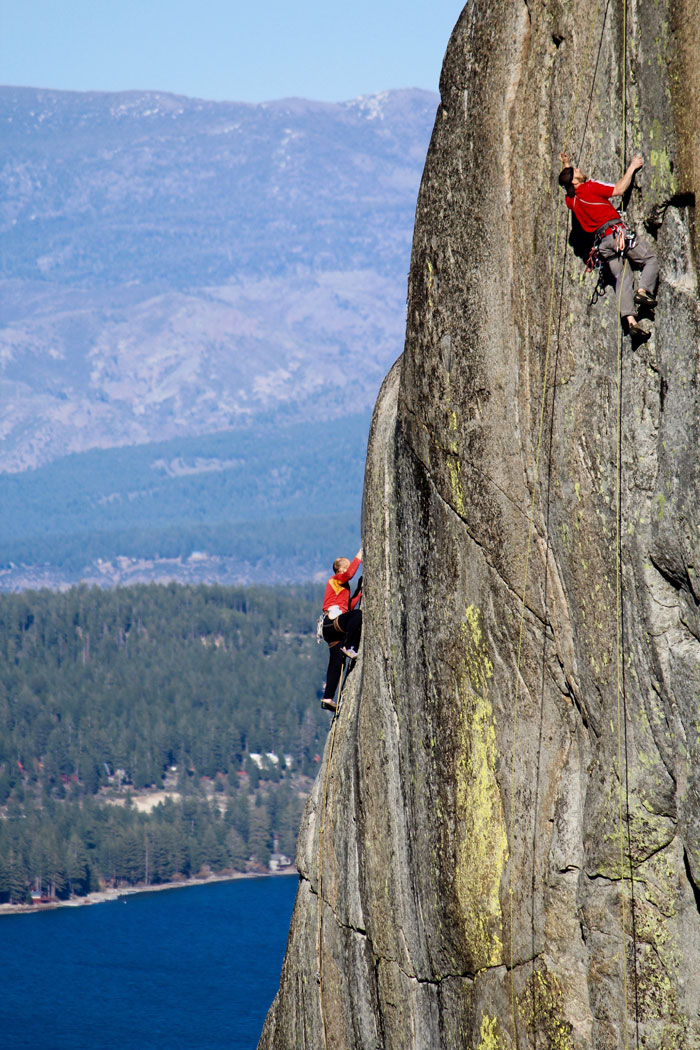

With a lot of second homes in the region, the Truckee Donner Land Trust works hard for Bay Area families as well as locals. “People come up here to play, and we’ve expanded their opportunities to play enormously through our efforts,” explains Norris. “Nothing’s more gratifying to me than to drive by one of our properties and see the trailhead jammed with cars and see people hiking or on horses and bikes, enjoying the land we’ve saved.”

Some worry that all this recreation might lead to environmental degradation, but Norris remains optimistic. “People are going to keep coming to the mountains. If we try to limit that, we risk becoming elitist. Our approach is to open up more space and funnel folks different places. So if one trailhead is becoming overcrowded, we try to point out other areas that aren’t as popular, but are just as beautiful.”

The Truckee Donner Land Trust sells some of the land they acquire to public entities, like California State Parks, the US Forest Service and the Department of Fish and Wildlife.”Usually those are bargain sales,” explains Norris. “Say we bought one property for 3.5 million, we’ll sell it to State Parks for 3 million.” Recently public entities have become reticent about acquiring land because of costs associated with management. So the Land Trust picks up the slack; they currently own and manage around 2,200 acres of land.

“It’s not just about stopping development,” explains Stewardship Director John Svahn. “We spend two thirds of our operating budget on stewardship and restoration.” That ranges from people on the property with pulawskis and chainsaws building trails and removing windfall from winter storms, to conducting scientific studies on meadow ecology.

“You can’t fix hundreds of years of neglect with a bunch of hippies and hatchets,” Norris muses. Mismanagement for fire suppression means some properties managed by the Land Trust have 600 trees per acre where there should be 60. So they use heavy machinery and cut trees.

“All of our forest thinning is dictated and prescribed by a habitat-oriented forester,” explains Norris. “Very few of the trees we cut ever get milled into lumber. Most of them either go to a biomass generation plant or they get chipped and end up decomposing on the forest floor.”

One of the most controversial projects in recent years has been the rehabilitation of the Van Norden Meadow, at the headwaters of the Yuba River. “That property contains an illegal dam that’s impounding state water. We have two state agencies threatening legal action if we don’t do something about it,” explains Norris. “We’re going to have to drain the reservoir, which is unsettling, especially during drought.”

But in a functioning Sierra meadow, snow melts and goes into a creek. During spring floods, the meadow absorbs water like a sponge and throughout the warmer summer months it slowly releases cold water. “A meadow is like a natural aquifer, it’s a very efficient way to store water,” Norris says. “State agencies are finally waking up to this. But we need more education to get the public on board.”

Like most non-profits, their biggest challenge is financial. “We function on the good will and charitable intent of our supporters,” explains Norris. “We get 1,200 to two thousand contributions every year, ranging from five bucks to a million dollars. And we appreciate every single one.”

Without such a dedicated staff, that money would not leverage nearly as much impact. “Typically, for the amount of acreage we save, we’d have a staff of fifteen or so,” explains KV Van Lom, the Communications Director. “With only six of us, there’s a tremendous amount of pressure. But we’re all incredibly dedicated and passionate about what we do.”

Another significant hurdle is political. The area is represented by two extremely conservative congressmen, LaMalfa and McClintock, who are often opposed to expanding public lands and recreational opportunities.

Despite this kind of opposition, the Land Trust and the organizations they partner with have permanently altered development patterns in their corner of the state. “At first developers didn’t take us very seriously,” Eaton remembers. “So we had to sue a few times. Now, most developers realize that they’re going to have to deal with environmentalists eventually and it’s more efficient to negotiate at the beginning. It’s rare to end in litigation these days.”

Eaton is convinced that local land trusts hold promise for wild lands everywhere. “There’s just a continual demand for development,” he explains. “If you like to hike, or bike, or ski, you need a land trust to preserve open space. Not just for recreational opportunities, but for habitat. A little patch here and there isn’t enough. We need large connected areas. That’s where a land trust comes in.”

Learn more about your local land trust at findalandtrust.org.

Young men from Troop 267 working on their Eagle Scout Project and helping with trail building and maintenance. Photo: TDLT

Mountain biking made available on the Land Trust’s protected open space. Photo: Emma Garrard/Sierra Sun