- California Enduro Series Announces 2024 Schedule - 11/19/2023

- ASHLAND MOUNTAIN CHALLENGE 2023 – CES RACE REPORT - 10/04/2023

- China Peak Enduro 2023 – CES Race Report - 09/04/2023

In praise of moderate rock

By Leonie Sherman

There’s not much that can convince me to skip out on eight days of High Sierra cross-country rambling. But when Brandon offered to climb the North Ridge of Lone Pine Peak with me, I only needed about 30 seconds to abandon my plans and submit to the siren call of the mountain. Every High Sierra climbing book raves about this “super mega ultra classic” route and I’d been denied twice already.

If you’re escaping the congested freeways and snarling humans of Southern California, the sight of bulky Lone Pine Peak heralds your arrival in the Land of Big Mountains. Rising straight out of the barren desert, the peak’s lower flanks start in dusty hills and culminate in crenelated granite and fluted spires. Looming over the town that shares it name, this mountain dominates the skyline of the southernmost High Sierra. Tourists often mistake it for Mt. Whitney; when viewed from the Alabama Hills, the tallest mountain in the lower 48, many miles distant, is dwarfed by this prominent peak.

The list of people who have first ascents on Lone Pine Peak is a veritable who’s who of California climbing. In 1925, the original Sierra hard man Norman Clyde became the first European to stand on the summit; Warren Harding climbed the Northeast Face almost three decades later. Fred Beckey showed up in 1969 to conquer the the Bastille Buttress; he returned four years later to climb a grade IV route that’s rated 5.10+. Internationally acclaimed photographer Galen Rowell put up two bold routes in the winter of 1970. And Em Holland, with her off-width master husband Bruce Bindner, climbed a grade V, 5.10, A3 route in 1999, recently free climbed by the soon-to-be-legendary climbing couple Amy Ness and Myles Moser.

The mile-wide 3,000 ft. big wall on the peak’s south face attracts climbers from around the world and features the most poetically named routes on the peak: Streets of the Mountains, Land of Little Rain, Dynamo-Hum, the Windhorse.

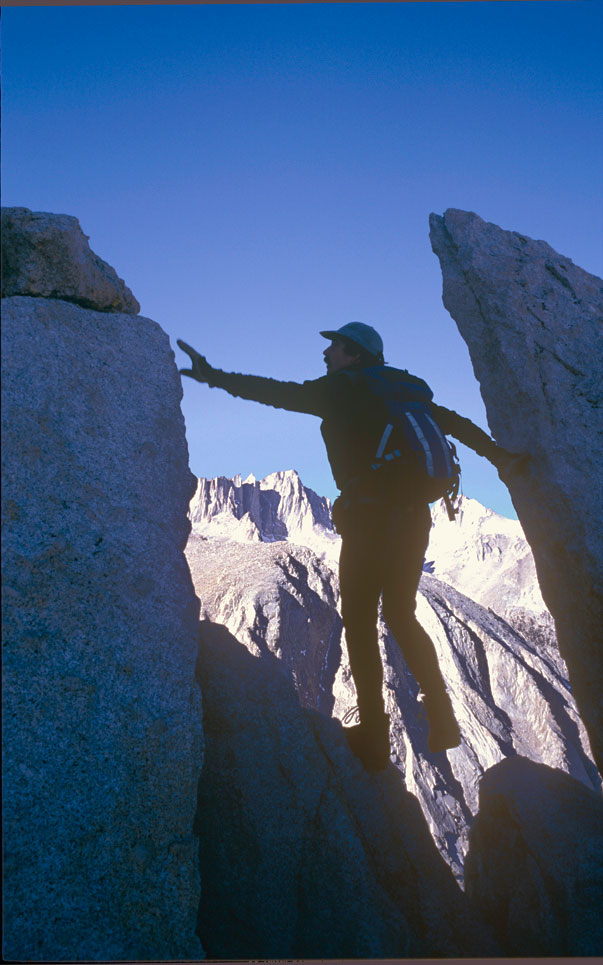

What the North Ridge lacks in poetry it makes up for in aesthetic appeal. This sweeping proud line rises over 7,000 vertical feet from the monochrome baking valley floor to the sparkling granite pinnacle. The complete route from sagebrush to summit was first climbed in 1986. Most mountaineers follow the classic route put up in 1952, which features a three and a half mile approach, a mere 5,000 ft. of gain and about 1,500 ft. of technical climbing.

This route is rated grade III, 5.5, by R.J. Secor and Peter Croft. The grade is a highly subjective rating that refers to how long a climb will take. Secor claims grade III means you should allow 4-7 hours to complete the route. Climbing Magazine estimates the climb of Lone Pine Peak’s North Ridge will take most people ten hours and suggests the descent will take five.

Amy Ness can climb the North Ridge in a casual morning and be back at the Whitney Portal Store for an afternoon shift. Myles likes to add the 17 pitches of 5.9 climbing on nearby Mt. Irvine’s East Buttress for a complete day. Most mere mortals want a pre-dawn start and will be lucky to return to their car by dark. One of the most skilled climbers I know bailed at the base because it’s Just So Long.

The 5.5 rating is deceptive. A friend of mine’s nine-year old daughter climbed a 5.8 the second time visiting our local gym, but she won’t be attempting the North Ridge of Lone Pine Peak anytime soon. A single pitch of top-roped gym climbing is to an alpine back-country ascent what riding down the driveway on a tricycle is to riding down 18,491 ft. Pico de Orizaba on a unicycle. What a kazoo solo is to Beethoven’s Fifth; what a walk to the corner store is to hiking the 3,000+ mile Continental Divide Trail in a single season. The rating may be easy, but the North Ridge of Lone Pine Peak will probably kick your butt.

It won’t increase your finger strength, force you to rely on a desperate ring lock or demand that you grovel up a gnarly chimney. Nobody’s doing any super fly heel hooks or battling with barely perceptible crimpers. There’s nothing to brag to your buddies about in the parking lot. You’ll just stretch your imagination, challenge your endurance and have a great time as you cruise what my friend Emma calls “five fun” climbing.

Besides, the further you get from a trailhead, the less accurate the rating. The venerable Doug Robinson has climbed the North Ridge of Lone Pine Peak over a dozen times and says it never goes easier than 5.8. Secor admits there’s an awkward 5.7 off-width section and a 5.7 lie-back pitch. Route-finding is a major challenge: Peter Croft offers only a thin paragraph of description, which includes: “basically stay on the right side of the ridge to the summit.” There’s probably a Super Topo somewhere that details each hold and belay stance, but I never saw it. Choosing your own adventure on an ocean of granite is a large part of the fun on the North Ridge of Lone Pine Peak.

One problem with a moderate rating is knowing when to pull out the rope. If you start pitching it out too early you’re wasting time, too late and you’re frantic and cursing. Being the weaker link in our climbing chain, Brandon and I resolved to free solo everything I could. When I got nervous we pulled out the rope and climbed the most difficult route we could see. We never did encounter the old fixed ring piton Secor talks about but we found four pitches of challenging climbing and hours of physical exciting scrambling. We topped out at 12,944 ft. around 2pm, visions of veggie burgers at the Portal Store dancing in our heads.

The vision that danced before our eyes was more spectacular than the finest burger and fries. Lone Pine Peak, lying just off the spine of the Sierra, provides a stellar view of the crest. Three of the tallest mountains in California – Whitney, Russell and Langley – were visible from our airy perch. The jagged teeth of Corcoran, LeConte, Mallory and Irvine commanded the western skyline, while the vast expanse of the Owens Valley stretched away to the east.

Everyone knows the summit is only halfway, but we’d been assured of a pleasant boot ski descent, a loose and gentle scree slope, twenty minutes max. So we lingered on top, savoring the view, perusing the register, calling out the names of friends, before we started skipping south along a sandy ridge. Hung a right and began picking our way down steep loose sand towards Grass Lakes and Little Meysan Lake.

Our chosen chute featured sand on slab, minuscule ball bearings, and we skittered down about six hundred vertical feet before coming to a cliffy section. We down climbed with care, slid down another couple hundred feet and halted at a precipitous drop. My partner scouted to the south, I scouted to the north; we came up with sun cracked slings looped around a rock.

“Wrong chute?” I inquired, as Brandon tugged on the slings and added one of his own.

Brandon nodded, grimacing as he threaded the rope through the old tat.

Our twenty minute boot ski devolved into four hours of treacherous down climbing and sketchy rappelling, spitting us out on the shore of Little Meysan Lake at dusk, just in time for the evening hatch of mosquitos. As we filled up water bottles and swatted at winged bloodsuckers, a thundering noise turned my gaze back to the gully we’d just descended. Dust rose hundreds of feet in the air as a roaring freight train of rock fall obliterated the chute we’d been struggling in half an hour before.

I pointed and stammered, but Brandon, ever the competent climber, kept his focus on the important details. He didn’t even glance up.

“If we hustle, I think the taco truck in Independence will still be open.”

We did, and it was.