- Death Valley’s Battle With Climate Extremes - 01/01/2024

- The Future of Homewood - 12/05/2023

- Kula Cloth - 10/18/2023

Peaceful Valley Donkey Rescue: How a small non-profit is saving donkeys across the nation and beyond

When Mark and Amy Meyers’ horse seemed lonely, they purchased a donkey named Izzy to keep her company. A quarter of a century later they’ve helped over 12,500 other donkeys find homes through the non-profit they started, Peaceful Valley Donkey Rescue.

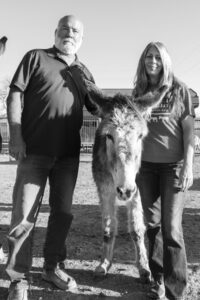

Mark and Amy with their first donkey, Izzy.

Not only did Izzy open their eyes to how friendly and loving donkeys can be, she opened their eyes to how many donkeys were out in the world suffering. Amy noticed one with a chest rubbed raw at a local store and the couple adopted the neglected animal, paying over $1,500 in veterinarian bills to bring him back to health.

“We stayed up every night to talk to him and by the end of a few months, he was just as friendly as Izzy,” Mark remembers fondly. “So we started buying more and more and fixing them up until we had about 25 donkeys. We decided we’d better do something or we were going to have a big problem.”

That problem became their new life’s calling. In 2000, a few years after adopting Izzy, they founded Peaceful Valley Donkey Rescue (PVDR) to adopt out their beloved docile donkeys. “If you sell them, there are no rules for what happens to them, but if you adopt them you can set rules,” explains Mark. “We have a reverter clause that if people can no longer care for them they get returned to us and we find them a new home.”

Five years later, Mark and Amy found a new home for themselves. They sold their other businesses and moved from their LA County home to Kern County to pursue their passion full time. “At first we thought this would be a good way to teach our sons about responsibility,” laughs Mark. “Now here we are with 50 employees, nationwide, and working in the Caribbean as well!”

Every donkey they adopt out undergoes a rigorous training regime. First, any health issues are tended to, and then, if male, they are castrated. After they’re healed up, trainers teach them to accept a halter, walk on lead and pick up all four hooves for trimming. If a donkey isn’t ready for adoption, they are often placed into a sanctuary program.

“We run usually 20 sanctuaries, each is about 500 acres and holds about 100 donkeys,” explains Mark. “They still get all the medical treatments, but they have much more freedom, and it’s cheaper than having to hand feed them every day. Every once in a while trainers go out and see if sanctuary donkeys are ready for training yet.”

In 2008 an unfortunate event rocketed PVDR to national attention. “Texas Parks and Wildlife decided it was a good idea to shoot 90-some-odd donkeys on the Rio Grande,” Mark sighs. “The story went nationwide and made them look real bad, so they called me to come and capture the donkeys instead. I moved out — temporarily I thought — to get things organized.”

Jennets at PVDR headquarters in San Angelo, Texas.

When the TV show Texas Country Reporter featured PVDR’s efforts, Mark’s phone blew up with calls and messages from folks in need of his services. “Once people found out there was some idiot out there willing to capture donkeys, they called and called and called. I actually lived apart from my wife for two years.”

Eventually the whole family was able to relocate to San Angelo, Texas, from where they oversee three training centers and 40 satellite adoption sites, three of which are in California. “We only deal with donkeys,” explains Mark. “Horse rescues are like Starbucks, there’s one on every corner. We are solving the donkey problem in the US, both wild and domestic.”

The domestic donkey problem usually involves abuse, neglect, hoarding and abandonment. Sometimes PVDR rescues donkeys from their inadequate homes; sometimes their work involves capturing them on abandoned property.

Wild jacks in the Wildrose portion of Death Valley NP.

The wild donkey problem involves National Park and military lands where donkeys are not protected. PVDR works with Death Valley National Park, Mojave National Preserve, Fort Irwin at the southern border of Death Valley, and NASA-Goldstone, which is on the northwest border of Fort Irwin. “Donkeys taught me patience and working with the federal government forced me to use it!” says Mark.

To rescue a donkey in the wilds or on abandoned property requires rounding them up without spooking them. “We use only the most humane capture methods. We don’t chase them, we don’t rope them and we don’t shock them,” explains Mark. “Our goal is to have them all placed into homes so it does no good to stress them out and teach them to hate humans!”

Wild donkeys in the StripedButte area of Death Valley NP.

PVDR uses finger traps, which look like fingers held in front of a face; donkeys are drawn by feed and bump their way in, but have trouble getting out. The traps are set wide, and the gates are narrowed each day until the donkeys can’t find their way out. Then trainers open a hole in the gate, connected to a trailer, and jump in with the donkeys, who move away from the human and into the trailer. “We use alfalfa as bait. It’s terrible feed for donkeys, too high in protein. But it smells good and they like it,” explains Mark. “If you’re going to bait a kid would you use candy or broccoli?”

Though they contract with federal agencies, they don’t accept any money from the government, choosing instead to rely on donations and grants. Last year PVDR raised $8 million through direct mail and relationship fundraising. Donors are an integral part of their team. “Without them, none of this would work!” explains Mark. “Everything we do from capture to training to adoption requires money.”

After more than two decades rescuing donkeys, PVDR is expanding their focus. “We are putting together a donkey history museum in Mesquite, Nevada, an hour north of Las Vegas, which opens in November of this year,” explains Mark. The museum will feature the donkey-related memorabilia he has been collecting for decades and have movable displays so there’s a new visitor experience for every winter.

Though wild donkeys rarely live past their teens, Izzy is now 23 and spends her days right outside Mark’s office door. “This can be a sad job, but it’s the best job I ever had,” explains Mark, as he recalls scenes of abuse and neglect. “This work needed doing. Donkeys needed saving and we are doing it, we are literally saving them.”

Betty White was born on Christmas Day and named for the actress who was a PVDR donor since 2006.

Visit donkeyrescue.org to learn more, and maybe even adopt a donkey.