- Josh Daiek: Boom and Bust - 03/19/2024

- Reconnecting the Past - 05/15/2023

- Striking Paydirt - 07/19/2022

The quest to allow cycling in federally designated Wilderness

By Kurt Gensheimer

Mountain bikers are proving to be a central part of the conservation movement (Blackburn/Brian Vernor).

Bicycles in federally protected Wilderness. Depending on who you ask, this is a linchpin issue for the future of conservation or you’ll get a blank stare and a “what about it?” Regardless of the reaction, the topic has been emotionally charged for decades, and as a result, there has been a lot of misunderstanding surrounding the original intent of the Wilderness Act of 1964. The issue of bicycles in Wilderness was recently rekindled when the Boulder-White Clouds region of Idaho, a coveted gem of backcountry mountain biking for generations, was designated federal Wilderness this past summer, shutting out mountain bike use forever.

Despite the fact that mountain bikes have been proven through numerous independent environmental studies to be as low-impact on trails as hiking and far lower impact than equestrian use, bicycles are still banned from 110 million acres of Wilderness (a number that grows nearly every year), despite other forms of permitted human-powered mechanical travel aids like backcountry ski gear, kayaks with oarlocks, anti-shock hiking poles and a plethora of climbing gear.

It wasn’t always this way. In fact, when the Wilderness Act of 1964 was originally passed, bicycles were permitted in Wilderness. The Rattlesnake Wilderness Act of 1980 specifically mentioned bicycling as “… primitive recreation, to include such activities as hiking, camping, backpacking, hunting, fishing, horse riding and bicycling …” And between 1981 and 1984, the Forest Service (USFS) interpreted the law as letting it evaluate case-by-case where bicycles could go in Wilderness. But in 1984, after only a handful of public complaints, the USFS finally concluded the ban meant no bicycles anywhere, anytime. This blanket ban has remained in effect. Public pressure brought about this regulation and it will take public pressure to modify it.

Conservation and Recreation

Congress passed the Wilderness Act in 1964 with the intent of conserving land from “expanding settlement” and “growing mechanization” while concurrently encouraging citizens to get out under their own power for the “… use and enjoyment of the American people …” One of the biggest misunderstandings of federally protected Wilderness is that it was created with the sole purpose of conservation, not recreation. But by simply reading the Act itself, it’s clear that Congress did not believe conservation and recreation were mutually exclusive. Both can exist. Besides, what good is conservation without the ability to experience protected lands in a low-impact, human-powered form of backcountry travel?

The blanket ban on bicycles in Wilderness has largely centered on two words – “mechanical transport.” The pressure put on the USFS to pass the regulation banning bicycles in 1984 used these two words originally intended for motorized forms of travel, conveniently lumping bicycles into that classification despite the fact that the USFS actually allowed mechanically assisted human-powered travel like cycling.

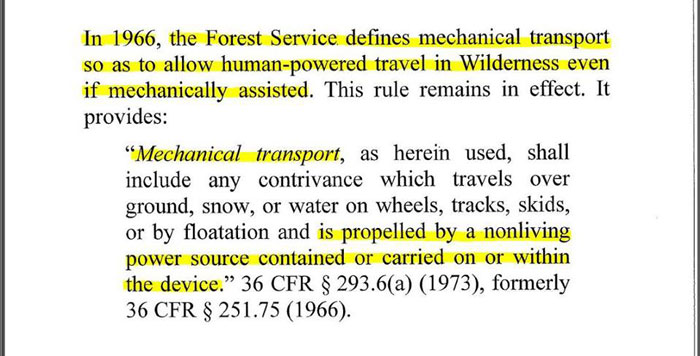

“Mechanical transport …” as defined by the USFS in 1966, “… shall include any contrivance which travels over ground, snow, or water on wheels, tracks, skids, or by flotation, and is propelled by a non-living power source …”

The key word here is “non-living,” which clearly establishes that bicycles were not originally intended for exclusion from Wilderness.

Despite all these clues proving beyond a doubt that Congress, and even the USFS for that matter, didn’t originally intend to exclude bicycles from Wilderness, what is the argument that has kept bicycles out since 1984? Unfortunately, nearly every argument against bicycles revolves around emotion and personal interest, not fact.

For years, the argument was that bicycles destroyed habitat, but science has since disproven the validity of that argument. Another case against bikes is that they ruin a non-cyclists Wilderness experience when encountering a cyclist, which can simply be written off as a case of bigotry. Not liking another person’s form of low-impact travel is not a valid reason for their exclusion. A third is that if Wilderness permits bikes, it will open the floodgates to hucksters wanting to “rip” and “shred” the backcountry, creating a safety issue. But the reality is this: those who desire bicycle access to Wilderness are respectful, responsible and conservation-minded folk just like non-cyclists in Wilderness. Besides, “shredding” when you’re deep in the backcountry goes against the tenets of self-preservation, and backcountry riders don’t take unnecessary risks.

Presenting a Solution

This year a new organization, the Sustainable Trails Coalition (STC), was co-founded by a Marin County mountain biker and a respected attorney who’s done legal work for the International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA). The STC has hired seasoned lobbyists to obtain a solution to the Wilderness dilemma. Contrary to what opponents are claiming, the STC does not seek to sue anyone, nor change the original meaning of the Wilderness Act of 1964. And despite alarmist claims, this update will not open the door to corporate greed and exploitation of Wilderness.

In fact, all the STC seeks is to establish what the USFS was doing from 1981 to 1984: letting local managers decide where bikes can go. Of course there are places that aren’t appropriate for bicycles; John Muir Trail and trails in Yosemite National Park are two prime examples. But there are literally millions of acres of extremely remote lands like the Boulder-White Clouds where bicycle use is the most efficient and logical means of backcountry travel.

Even if you are staunchly against bike access in Wilderness, there is still good reason why you should reconsider. The blanket ban is creating an involuntary anti-conservationist movement within the most devoted segment of recreationists. Hikers, equestrians and mountain bikers share a lot in common, and by working together, create an incredibly strong conservationist voice. But by banning bikes from Wilderness, that voice is weakened. And considering the continued growth of mountain biking, especially with America’s youth thanks to high school mountain bike leagues, the voice may continue to weaken if the blanket ban is not removed, potentially opening the door for future exploitation of resources.

Secondly, mountain bikers have proven to be a critical asset to land managers and a central part of the conservation movement, working with agencies to build and maintain sustainable trails that promote health, recreation and connecting with nature while providing a vitally important tourism economy for remote mountain communities.

Thirdly, historical trails in Wilderness areas are disappearing because of a lack of use and maintenance. Due to the highly efficient nature of a bicycle, riders will be able to more easily access these areas and prevent historically significant trails from disappearing forever, providing a benefit for all human-powered users. Trails are a part of America’s heritage, and just like the aspirations of federal Wilderness, they should be kept intact for future generations to enjoy.

Drop bars and skinny tires take well to the dirt on epic adventures (Specialized/Marcello Mariana).\

Although not currently threatened, the Lakes Basin region near Downieville could be proposed as future Wilderness (Kurt Gensheimer).

In Black & White

In 1966, the USFS defined “mechanical transport” as a device propelled by a “nonliving” power source, further proving bicycles were not intended to be excluded from Wilderness.

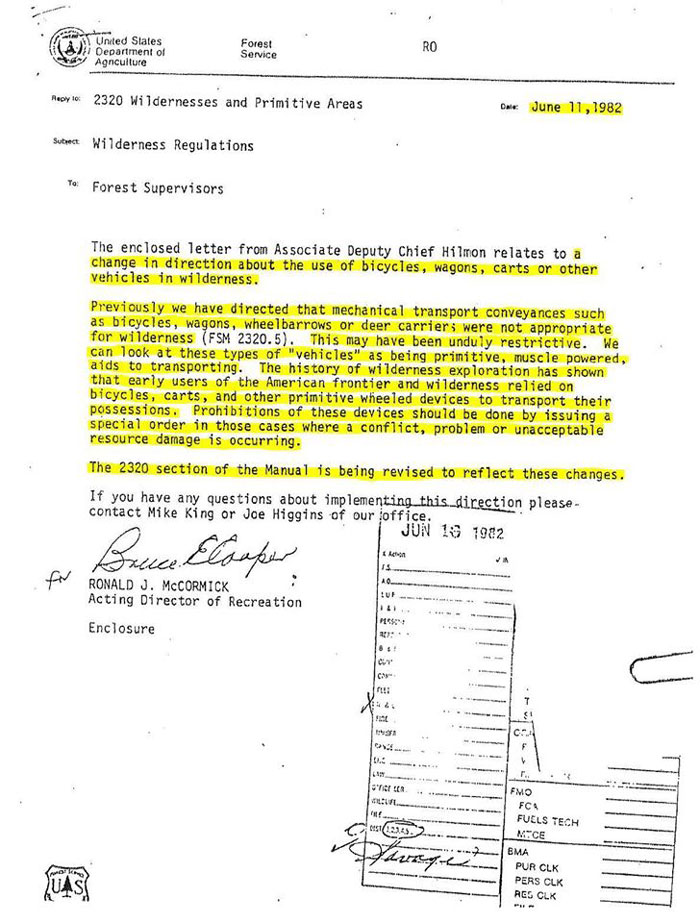

This 1982 USFS memorandum states the ban on bikes is an “editorial error,” proving the USFS intended to manage bicycles on a case-by-case basis, but due to only a few public complaints, the ban was never lifted.