- Death Valley’s Battle With Climate Extremes - 01/01/2024

- The Future of Homewood - 12/05/2023

- Kula Cloth - 10/18/2023

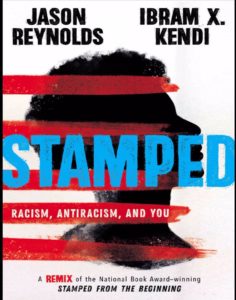

Bringing Books in the Back Country and Anti-Racism Everywhere

By Leonie Sherman

Normally I go to the wilderness to get away from screens. But I brought an iPad on my first post-covid backpacking trip. It was the only way I could read Ibram X Kendi and Jason Reynolds’ book Stamped: Racism, Anti-Racism and You. I suppose it’s a hopeful sign that the book is sold out that you can only access it electronically.

I needed to haul a big pack over a high pass and develop blisters to heal something broken inside me. I figured if I was going to run to the mountains and take a break from the grim cycle of death, police brutality and incompetent leaders, the least I could do was educate myself while I was out there. My iPad weighs about the same as two days of food, or just under 10% of my pack weight. It was worth it.

Kendi and Reynolds not-history book traces the rise of racism in Europe and the way it metasticized in the colonies that became the United States. It’s an eye opening primer, identifying the first racist (Portuguese author Durara), following the first slaves arrival in Virginia in 1619 and taking the reader through to Obama’s presidency. Stamped asks the reader to consider how slavery figured into the Revolutionary War (the UK had already abolished slavery and was pressuring the colonies to do the same), and walks them through the painful details of reconstruction. It introduces them to Phyllis Wheatley, WEB Du Bois, Ida B Wells, Malcolm X, the Black Power movement and the racism of modern films like Rocky and Planet of the Apes.

Kendi and Reynolds not-history book traces the rise of racism in Europe and the way it metasticized in the colonies that became the United States. It’s an eye opening primer, identifying the first racist (Portuguese author Durara), following the first slaves arrival in Virginia in 1619 and taking the reader through to Obama’s presidency. Stamped asks the reader to consider how slavery figured into the Revolutionary War (the UK had already abolished slavery and was pressuring the colonies to do the same), and walks them through the painful details of reconstruction. It introduces them to Phyllis Wheatley, WEB Du Bois, Ida B Wells, Malcolm X, the Black Power movement and the racism of modern films like Rocky and Planet of the Apes.

A reader will learn the terms segregationist and assimilationist and be challenged to become antiracist. It’s a remix of Kendi’s National Book Award-winning Stamped From the Beginning, packaged for a more distracted audience. Reynolds prose is fresh and acessible, transforming complex ideas into easily digested bite-sized chapters.

One significant and depressing take away is our nations’ long history of antiracist protests in response to police violence. After the world watched police attack unarmed protesters in Birmingham in 1963, President John F Kennedy recognized something was wrong and pledged to pass a Civil Rights Act. His successor, Lyndon B Johnson, went a step further and signed the Voting Rights Act into law in 1965. But in 1992, four racist cops were acquitted after savagely beating Rodney King. Protests ripped through the country; nothing changed. And 55 years after the Voting Rights Act, racist voter suppression continues.

Due to our most recent antiracist protests, national conversation appears to be focusing on the systemic change our society needs. Putting violent racist cops on trial, banning carotid restraints and diverting money from police departments to social services are promising signs. We need regime change in November. But longer lasting change requires deeper reckoning.

Kendi and Reynolds don’t offer solutions or suggest action. Their book aims to help readers understand the present, how America got to be so racist that white men armed with AR-15s can storm a capitol building and emerge unharmed, while a black man can be shot for jogging, or murdered by those sworn to serve and protect for allegedly passing a counterfeit $20 bill.

But Kendi and Reynolds do mention that the survivors of the Salem witch trials and their families received reparations. Since our government can come up with billions of dollars to bail out businesses, surely they can cough up some money to begin to make amends to the descendants of African slaves who built this country. It’s nowhere near enough, but it’s a start.

My first night in the mountains I met a white woman who lived in South Africa until she was 8-years-old. I remembered being too young to understand apartheid, but old enough to know it was wrong. The US is in that same position now. Tens of thousands of people all over the world are protesting our brutal racist police force. Will we start the long slow march towards systemic change? Can we advance the arc of our nations’ history towards justice?

Dismantling racism is white peoples work. We need to do more than buy books or write articles. Becoming antiracist is like developing good posture; it requires constant daily attention. You slip up, you slouch; you mess up, you apologize. Eventually you build lifelong habits. You learn to stand up straight, you learn to bring an antiracist perspective to everything you do, whether it’s running an office or a cash register, taking a class or teaching one.

Many backpackers recognize the existential threat posed by climate change. We know massive changes need to take place if we are to pass on a habitable world to our nieces and nephews and their children.

The changes required to address systemic racism in the US are of the same order of magnitude, and just as important. Kendi and Reynolds’ book can help us take the first step by understanding the origins of racism and the role it played in the educational, religious and political foundation of the US.

Sometimes when I’m backpacking, I get tired and discouraged because I’m not as strong as I used to be. But quitting is not an option. There may be dangerous river crossings, freezing hail, and thunderstorms. I might find somebody else’s trash and have to haul it out. I may get lost and need to ask for help. Throwing down my pack or pretending I know where I am won’t get me any closer to where I need to be. I have to shoulder my load and keep walking.

Similarly, I need to keep working towards the antiracist world I want my nephews and neices to live in. There are no shortcuts. For most of us, the work starts with a painful examination of our own racist tendencies. As Kendi reminds us, denial is the language of racism; confession is the language of antiracism. The work looks different for each of us. It needs to continue long after the fires of the most recent antiracist protests have burned out. Anti-Racism

PS I realize this is an deeply flawed analogy. I can choose not to go backpacking, Breonna Taylor cannot choose not to get shot in her bed while she sleeps. But to quote the lead singer from Consolidated: I haven’t got shit to say, but if I don’t say anything, well, how long will it be this way? Anti-Racism